Dom Sankt Jakob

Domplatz

Worth knowing

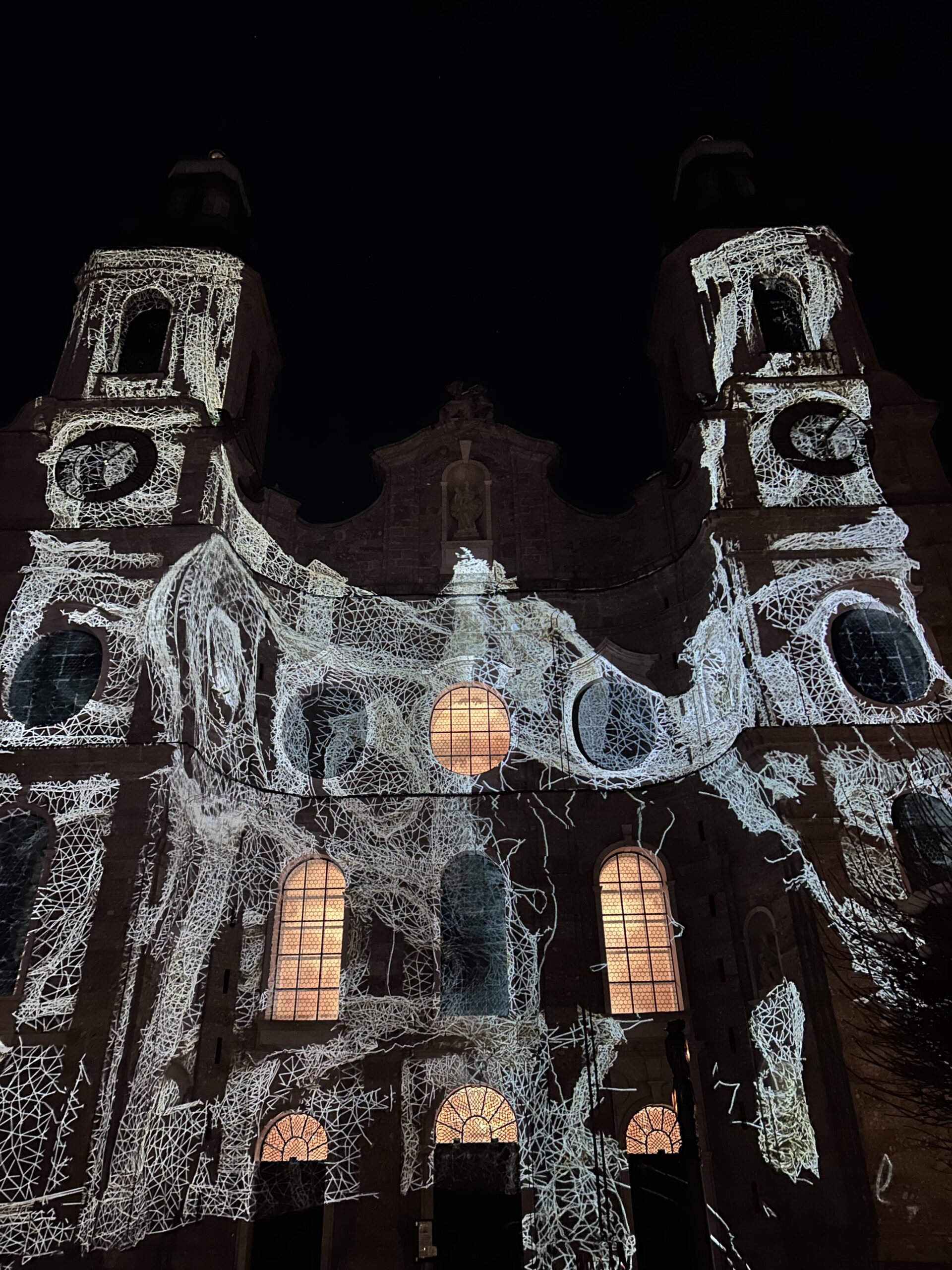

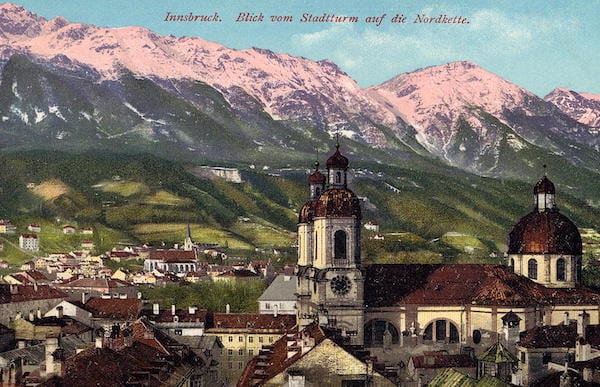

The history of the church from which today’s cathedral in the Old Town emerged is older than that of the city itself. When Count Berchtold V acquired the land south of the Inn from the Wilten Abbey in 1180—land on which Innsbruck would later be built—the exchange contract already mentioned a market church. At that time, Innsbruck was not yet an independent parish but merely a branch of Wilten Abbey. There was no talk of a bishop’s seat then. Nevertheless, the church was the center of the developing town, which at that time had neither the Golden Roof nor the Imperial Palace. A cemetery surrounded the church; the last graves were only removed in 1905 with the construction of the sewer system. It was only with the construction of the city tower, the town hall, the Neuhof, and other buildings on the Upper and Lower Town Squares in the late Middle Ages that things changed. In Albrecht Dürer’s famous watercolor, painted during his journey through Innsbruck in 1495, the parish church of St. James appears merely as one of many towers in the cityscape.

The fate of St. James was far from fortunate. The church burned down several times. The earthquake of 1689, which damaged almost all Innsbruck houses, did not spare the cathedral either. In 1724, after a complete redesign in the contemporary Baroque style, the church was consecrated. It was not fitting for a city like Innsbruck to have a half-finished ruin as its showpiece within the city walls. To finance the construction, a special tax on tobacco was introduced, and additional duties were levied. The former Lion House of Ferdinand II on the Inn, which had burned down in 1636, was rebuilt as a brewery and tavern to bring extra coins into the budget through Innsbruck’s thirst for beer. After the unexpected death of Johann Jakob Herkomer, originally intended as the construction manager, Johann Georg Fischer took over the project. A beautiful legend surrounds the large ceiling fresco by Cosmas Damian Asam (1686–1739). When the painter fell from the scaffolding during work, Saint John is said to have stretched out his hand to save the maestro from certain death. After World War I, the newly drawn border at the Brenner made it difficult to administer North and South Tyrol under one diocese. North Tyrol and Vorarlberg needed their own administration. Finally, in 1964, the former small branch of Wilten Abbey became the Cathedral of Innsbruck.

In 1944, like so many other churches, the cathedral was damaged in an air raid. The interior and exterior were quickly renovated in the first post-war years to restore the proper representation of the clerical administrative center of western Austria as soon as possible. The sturdy church towers rise high into the sky, adorned with imposing gargoyles. A rider sits atop the gable above the entrance. The front façade is decorated with statues of various saints, including Saint Notburga, one of Innsbruck’s patron saints, and Saint Romedius, who is said to have ridden from Tyrol to Rome on a bear. Veneration of saints reached its peak in the 17th and 18th centuries. Baroque culture understood the importance of inspiring people for the Roman Church with good stories, the integration of popular legends, and impressive sound. The many bells of St. James remain a spectacle even today. The Marian bell, cast at the traditional Grassmayr foundry in Innsbruck, weighs over seven tons. On special occasions, the cathedral’s bells ring under the expert execution of a dedicated bell ringer. The interior of the cathedral is crowned by a dome above the famous devotional image Mariahilf by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553). This masterpiece of the Innsbruck Cathedral came as a souvenir under the art-loving provincial prince Leopold V. Since 1650, it has hung on the high altar of the cathedral, with only a brief interruption during wartime. During World War II, the image of the Virgin was taken to the nearby Ötztal to protect it from bombings. Anyone walking attentively through the city will find the Virgin in many house façades or fountains. Even outside Innsbruck, the image is widespread in North and South Tyrol. Alongside the devotional image, a second monument survived the transformation from the old to the new church and was relocated: the tomb of Maximilian III of Austria occupies a significant part of the nave. The kneeling provincial prince of Tyrol is flanked by Saint George, the patron of the Teutonic Order. Archduke Eugen, who served as the supreme military commander of Tyrol in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I and was also a member of the Teutonic Order, is buried here as well.

Today, the cathedral square is a popular meeting place in the Old Town, just a few steps from the Golden Roof yet slightly away from the tourist crowds. Thanks to several cafés and student apartments in the picturesque houses around the fountain, young people have rediscovered the square in front of the church and brought it back to life.

Baroque: art movement and art of living

Anyone travelling in Austria will be familiar with the domes and onion domes of churches in villages and towns. This form of church tower originated during the Counter-Reformation and is a typical feature of the Baroque architectural style. They are also predominant in Innsbruck's cityscape. Innsbruck's most famous places of worship, such as the cathedral, St John's Church and the Jesuit Church, are in the Baroque style. Places of worship were meant to be magnificent and splendid, a symbol of the victory of true faith. Religiousness was reflected in art and culture: grand drama, pathos, suffering, splendour and glory combined to create the Baroque style, which had a lasting impact on the entire Catholic-oriented sphere of influence of the Habsburgs and their allies between Spain and Hungary.

The cityscape of Innsbruck changed enormously. The Gumpps and Johann Georg Fischer as master builders as well as Franz Altmutter's paintings have had a lasting impact on Innsbruck to this day. The Old Country House in the historic city centre, the New Country House in Maria-Theresien-Straße, the countless palazzi, paintings, figures - the Baroque was the style-defining element of the House of Habsburg in the 17th and 18th centuries and became an integral part of everyday life. The bourgeoisie did not want to be inferior to the nobles and princes and had their private houses built in the Baroque style. Pictures of saints, depictions of the Mother of God and the heart of Jesus adorned farmhouses.

Baroque was not just an architectural style, it was an attitude to life that began after the end of the Thirty Years' War. The Turkish threat from the east, which culminated in the two sieges of Vienna, determined the foreign policy of the empire, while the Reformation dominated domestic politics. Baroque culture was a central element of Catholicism and its political representation in public, the counter-model to Calvin's and Luther's brittle and austere approach to life. Holidays with a Christian background were introduced to brighten up people's everyday lives. Architecture, music and painting were rich, opulent and lavish. In theatres such as the Comedihaus dramas with a religious background were performed in Innsbruck. Stations of the cross with chapels and depictions of the crucified Jesus dotted the landscape. Popular piety in the form of pilgrimages and the veneration of the Virgin Mary and saints found its way into everyday church life. Multiple crises characterised people's everyday lives. In addition to war and famine, the plague broke out particularly frequently in the 17th century. The Baroque piety was also used to educate the subjects. Even though the sale of indulgences was no longer a common practice in the Catholic Church after the 16th century, there was still a lively concept of heaven and hell. Through a virtuous life, i.e. a life in accordance with Catholic values and good behaviour as a subject towards the divine order, one could come a big step closer to paradise. The so-called Christian edification literature was popular among the population after the school reformation of the 18th century and showed how life should be lived. The suffering of the crucified Christ for humanity was seen as a symbol of the hardship of the subjects on earth within the feudal system. People used votive images to ask for help in difficult times or to thank the Mother of God for dangers and illnesses they had overcome.

The historian Ernst Hanisch described the Baroque and the influence it had on the Austrian way of life as follows:

„Österreich entstand in seiner modernen Form als Kreuzzugsimperialismus gegen die Türken und im Inneren gegen die Reformatoren. Das brachte Bürokratie und Militär, im Äußeren aber Multiethnien. Staat und Kirche probierten den intimen Lebensbereich der Bürger zu kontrollieren. Jeder musste sich durch den Beichtstuhl reformieren, die Sexualität wurde eingeschränkt, die normengerechte Sexualität wurden erzwungen. Menschen wurden systematisch zum Heucheln angeleitet.“

The rituals and submissive behaviour towards the authorities left their mark on everyday culture, which still distinguishes Catholic countries such as Austria and Italy from Protestant regions such as Germany, England or Scandinavia. The Austrians' passion for academic titles has its origins in the Baroque hierarchies. The expression Baroque prince describes a particularly patriarchal and patronising politician who knows how to charm his audience with grand gestures. While political objectivity is valued in Germany, the style of Austrian politicians is theatrical, in keeping with the Austrian bon mot of "Schaumamal".

Maria help Innsbruck!

The veneration of saints and popular piety always walked a fine line between faith, superstition and magic. In the Alps, where people were more exposed to the almost inexplicable environment than in other regions, this form of faith took on remarkable and often bizarre forms. Saints were invoked for help with various everyday tasks. St Anne was supposed to protect the house and hearth, while St Notburga of Rattenberg, who was particularly popular in Tyrol, was prayed to for a good harvest. When fertilisers and agricultural machinery were increasingly used for this purpose, she rose to become the patron saint of women wearing traditional costumes. Miners entrusted their fate in their dangerous job underground to St Barbara and St Bernard. The chapel at the manor houses in Halltal near Innsbruck provides a fascinating insight into the world of faith between Begging spirit and worship of various local patron saints. The saint who still outshines all others in terms of veneration is Mary. From the consecration of herbs at the Assumption of Mary to the right-turning water in Maria Waldrast at the foot of the Serles and votive images in churches and chapels, she is a favourite permanent guest in popular piety. If you take a careful stroll through Innsbruck, you will find a special image on the facades of buildings time and again: the Gnadenbild Mariahilf by Lucas Cranach (ca. 1472 - 1553).

Cranach's Madonna is one of the most popular and most frequently copied depictions of Mary in the Alpine region. The painting is a reinterpretation of the classic iconographic Mother of God. Similar to the Mona Lisa da Vinci, which was painted at a similar time, Mary smiles mischievously at the viewer. Cranach dispensed with any form of sacralisation such as a crescent moon or halo and has her appear in contemporary everyday clothing. The red-blonde hair of mother and child transports her from Palestine to Europe. The saint and virgin Mary became an ordinary woman with a child from the upper middle class of the 16th century.

The creation, journey and veneration of the Mariahilf miraculous image tell the story of the Reformation, Counter-Reformation and popular piety in the German lands in miniature. The odyssey of the painting, which measures just 78 x 47 cm, began in what is now Thuringia at the royal court, one of the cultural centres of Europe at the time. Elector Frederick III of Saxony (1463 - 1525) was a pious man. He owned one of the most extensive collections of relics of the time. Despite his deep roots in the popular belief in relics and his pronounced penchant for Marian devotion, he supported Martin Luther in 1518 not only for religious reasons, but also for reasons of power politics. Free passage from the powerful prince and accommodation at Wartburg Castle enabled Luther to work on the German translation of the Holy Scriptures and his vision of a new, reformed church.

As was customary at the time, Friedrich also had a Art Director in his entourage. Lucas Cranach had been a court painter in Wittenberg since 1515. Like other painters of his time, Cranach was not only extremely productive, but also extremely enterprising. In addition to his artistic activities, he ran a pharmacy and a wine tavern in Wittenberg. Thanks to his financial prosperity and reputation, he was mayor of the town from 1528. Cranach was regarded as a quick painter with great output. He recognised art as a medium for capturing and disseminating the spirit of the times. Like Albrecht Dürer, he created popular works with a wide reach. His portraits of the high society of the time still characterise our image of celebrities today, such as those of his employer Frederick, Maximilian I, Martin Luther and his colleague Dürer.

Cranach and the church critics Philipp Melanchthon and Martin Luther met at Wittenberg Castle. It was through this acquaintance at the latest that the artist became a supporter of the new, reformed Christianity, which did not yet have an official manifestation. The ambiguities in the religious beliefs and practices of this period before the official schism are reflected in Cranach's works. Despite Luther and Melanchthon's rejection of the veneration of saints, the cult of the Virgin Mary and iconographic representations in churches, Cranach continued to paint for his patrons according to their taste.

Just as unclear as the transition from one denomination to another in the 16th century is the date of origin of the The miraculous image of Mariahilf. Cranach painted it sometime between 1510 and 1537 either for the household of Frederick's sister-in-law, Duchess Barbara of Saxony, or for the Church of the Holy Cross in Dresden. Art experts are still divided today. The friendship between Cranach and Martin Luther suggests that Cranach painted it after his conversion to Lutheranism and that this secularised depiction of a mother and child is an expression of a new religious world view. However, it is entirely possible that the business-minded artist painted the picture without any ideological background, but as an expression of the fashion of the time even before Luther's arrival in Wittenberg.

After Frederick's death, Cranach entered the service of his successor, John Frederick I of Saxony. When his employer was taken prisoner by the emperor after the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, court painter Cranach followed him to Augsburg and Innsbruck despite his advanced age. After five years in the wake of the hostage, who was probably housed in luxury, Cranach returned to Wittenberg, where he succumbed to his biblical age by the standards of the time.

The Gnadenbild Mariahilf was transferred to the Kunstkammer of the Saxon sovereign during the turbulent years of the confessional wars, probably to save it from destruction by zealous iconoclasts. Almost 65 years later, like its creator before it, it was to find its way to Innsbruck along winding paths. When the art-loving Bishop of Passau from the House of Habsburg was a guest at court in Dresden in 1611, he chose Cranach's miraculous painting as a gift and took it with him to his prince-bishop's residence on the Danube. His cathedral dean saw it there and was so impressed that he had a copy made for his home altar. A pilgrimage cult quickly developed around the picture.

When the Bishop of Passau became Archduke Leopold V of Austria and Prince of Tyrol seven years later, the popular painting moved with its owner to the court in Innsbruck. His Tuscan wife Claudia de Medici kept the cult of the Virgin Mary in the Italian tradition alive even after his death. Both the Servite Church and the Capuchin monastery were given altars and images of the Virgin Mary. However, nothing was more popular than Cranach's miraculous image. In order to protect the city during the Thirty Years' War, the image was often taken from the court chapel and displayed for public veneration. During these mass prayers, the desperate population of Innsbruck shouted a loud "Maria Hilf" ("Mary Help") at the small painting, a practice that had become part of popular belief thanks to the Jesuits. In 1647, at the moment of greatest need, the Tyrolean estates swore to build a church around the painting to protect the country from devastation by Bavarian and Swedish troops. The fact that the reformed depiction of St Mary, painted by a friend of Martin Luther, was invoked to protect the city from Protestant troops is probably not without a certain irony.

Although the Mariahilf church was built, the painting was exhibited in 1650 in the parish church of St Jakob within the safe city walls. The newly built church received a copy made by Michael Waldmann. It was not to be the last of its kind. The motif and Cranach's depiction of the Mother of God became extremely popular and can still be found today not only in churches but also on countless private houses. Art became a mass phenomenon through these copies. The image of the Virgin Mary had migrated from the private property of the Saxon prince to the public sphere. Centuries before Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Cranach and Dürer had become widely copied artists and their paintings had become part of public space and everyday life. The original of the The miraculous image of Mariahilf may hang in St Jacob's Cathedral, but the copy and the parish that grew up around it gave its name to an entire district.

Believe, Church and Power

Die Fülle an Kirchen, Kapellen, Kruzifixen und Wandmalereien im öffentlichen Raum wirkt auf viele Besucher Innsbrucks aus anderen Ländern eigenartig. Nicht nur Gotteshäuser, auch viele Privathäuser sind mit Darstellungen der Heiligen Familie oder biblischen Szenen geschmückt. Der christliche Glaube und seine Institutionen waren in ganz Europa über Jahrhunderte alltagsbestimmend. Innsbruck als Residenzstadt der streng katholischen Habsburger und Hauptstadt des selbsternannten Heiligen Landes Tirol wurde bei der Ausstattung mit kirchlichen Bauwerkern besonders beglückt. Allein die Dimension der Kirchen umgelegt auf die Verhältnisse vergangener Zeiten sind gigantisch. Die Stadt mit ihren knapp 5000 Einwohnern besaß im 16. Jahrhundert mehrere Kirchen, die in Pracht und Größe jedes andere Gebäude überstrahlte, auch die Paläste der Aristokratie. Das Kloster Wilten war ein Riesenkomplex inmitten eines kleinen Bauerndorfes, das sich darum gruppierte. Die räumlichen Ausmaße der Gotteshäuser spiegelt die Bedeutung im politischen und sozialen Gefüge wider.

Die Kirche war für viele Innsbrucker nicht nur moralische Instanz, sondern auch weltlicher Grundherr. Der Bischof von Brixen war formal hierarchisch dem Landesfürsten gleichgestellt. Die Bauern arbeiteten auf den Landgütern des Bischofs wie sie auf den Landgütern eines weltlichen Fürsten für diesen arbeiteten. Damit hatte sie die Steuer- und Rechtshoheit über viele Menschen. Die kirchlichen Grundbesitzer galten dabei nicht als weniger streng, sondern sogar als besonders fordernd gegenüber ihren Untertanen. Gleichzeitig war es auch in Innsbruck der Klerus, der sich in großen Teilen um das Sozialwesen, Krankenpflege, Armen- und Waisenversorgung, Speisungen und Bildung sorgte. Der Einfluss der Kirche reichte in die materielle Welt ähnlich wie es heute der Staat mit Finanzamt, Polizei, Schulwesen und Arbeitsamt tut. Was uns heute Demokratie, Parlament und Marktwirtschaft sind, waren den Menschen vergangener Jahrhunderte Bibel und Pfarrer: Eine Realität, die die Ordnung aufrecht hält. Zu glauben, alle Kirchenmänner wären zynische Machtmenschen gewesen, die ihre ungebildeten Untertanen ausnützten, ist nicht richtig. Der Großteil sowohl des Klerus wie auch der Adeligen war fromm und gottergeben, wenn auch auf eine aus heutiger Sicht nur schwer verständliche Art und Weise. Verletzungen der Religion und Sitten wurden in der späten Neuzeit vor weltlichen Gerichten verhandelt und streng geahndet. Die Anklage bei Verfehlungen lautete Häresie, worunter eine Vielzahl an Vergehen zusammengefasst wurde. Sodomie, also jede sexuelle Handlung, die nicht der Fortpflanzung diente, Zauberei, Hexerei, Gotteslästerung – kurz jede Abwendung vom rechten Gottesglauben, konnte mit Verbrennung geahndet werden. Das Verbrennen sollte die Verurteilten gleichzeitig reinigen und sie samt ihrem sündigen Treiben endgültig vernichten, um das Böse aus der Gemeinschaft zu tilgen. Bis in die Angelegenheiten des täglichen Lebens regelte die Kirche lange Zeit das alltägliche Sozialgefüge der Menschen. Kirchenglocken bestimmten den Zeitplan der Menschen. Ihr Klang rief zur Arbeit, zum Gottesdienst oder informierte als Totengeläut über das Dahinscheiden eines Mitglieds der Gemeinde. Menschen konnten einzelne Glockenklänge und ihre Bedeutung voneinander unterscheiden. Sonn- und Feiertage strukturierten die Zeit. Fastentage regelten den Speiseplan. Familienleben, Sexualität und individuelles Verhalten hatten sich an den von der Kirche vorgegebenen Moral zu orientieren. Das Seelenheil im nächsten Leben war für viele Menschen wichtiger als das Lebensglück auf Erden, war dies doch ohnehin vom determinierten Zeitgeschehen und göttlichen Willen vorherbestimmt. Fegefeuer, letztes Gericht und Höllenqualen waren Realität und verschreckten und disziplinierten auch Erwachsene.

Während das Innsbrucker Bürgertum von den Ideen der Aufklärung nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen zumindest sanft wachgeküsst wurde, blieb der Großteil der Menschen weiterhin der Mischung aus konservativem Katholizismus und abergläubischer Volksfrömmigkeit verbunden. Religiosität war nicht unbedingt eine Frage von Herkunft und Stand, wie die gesellschaftlichen, medialen und politischen Auseinandersetzungen entlang der Bruchlinie zwischen Liberalen und Konservativ immer wieder aufzeigten. Seit der Dezemberverfassung von 1867 war die freie Religionsausübung zwar gesetzlich verankert, Staat und Religion blieben aber eng verknüpft. Die Wahrmund-Affäre, die sich im frühen 20. Jahrhundert ausgehend von der Universität Innsbruck über die gesamte K.u.K. Monarchie ausbreitete, war nur eines von vielen Beispielen für den Einfluss, den die Kirche bis in die 1970er Jahre hin ausübte. Kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg nahm diese politische Krise, die die gesamte Monarchie erfassen sollte in Innsbruck ihren Anfang. Ludwig Wahrmund (1861 – 1932) war Ordinarius für Kirchenrecht an der Juridischen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck. Wahrmund, vom Tiroler Landeshauptmann eigentlich dafür ausgewählt, um den Katholizismus an der als zu liberal eingestuften Innsbrucker Universität zu stärken, war Anhänger einer aufgeklärten Theologie. Im Gegensatz zu den konservativen Vertretern in Klerus und Politik sahen Reformkatholiken den Papst nur als spirituelles Oberhaupt, nicht aber als weltlich Instanz, an. Studenten sollten nach Wahrmunds Auffassung die Lücke und die Gegensätze zwischen Kirche und moderner Welt verringern, anstatt sie einzuzementieren. Seit 1848 hatten sich die Gräben zwischen liberal-nationalen, sozialistischen, konservativen und reformorientiert-katholischen Interessensgruppen und Parteien vertieft. Eine der heftigsten Bruchlinien verlief durch das Bildungs- und Hochschulwesen entlang der Frage, wie sich das übernatürliche Gebaren und die Ansichten der Kirche, die noch immer maßgeblich die Universitäten besetzten, mit der modernen Wissenschaft vereinbaren ließen. Liberale und katholische Studenten verachteten sich gegenseitig und krachten immer aneinander. Bis 1906 war Wahrmund Teil der Leo-Gesellschaft, die die Förderung der Wissenschaft auf katholischer Basis zum Ziel hatte, bevor er zum Obmann der Innsbrucker Ortsgruppe des Vereins Freie Schule wurde, der für eine komplette Entklerikalisierung des gesamten Bildungswesens eintrat. Vom Reformkatholiken wurde er zu einem Verfechter der kompletten Trennung von Kirche und Staat. Seine Vorlesungen erregten immer wieder die Aufmerksamkeit der Obrigkeit. Angeheizt von den Medien fand der Kulturkampf zwischen liberalen Deutschnationalisten, Konservativen, Christlichsozialen und Sozialdemokraten in der Person Ludwig Wahrmunds eine ideale Projektionsfläche. Was folgte waren Ausschreitungen, Streiks, Schlägereien zwischen Studentenverbindungen verschiedener Couleur und Ausrichtung und gegenseitige Diffamierungen unter Politikern. Die Los-von-Rom Bewegung des Deutschradikalen Georg Ritter von Schönerer (1842 – 1921) krachte auf der Bühne der Universität Innsbruck auf den politischen Katholizismus der Christlichsozialen. Die deutschnationalen Akademiker erhielten Unterstützung von den ebenfalls antiklerikalen Sozialdemokraten sowie von Bürgermeister Greil, auf konservativer Seite sprang die Tiroler Landesregierung ein. Die Wahrmund Affäre schaffte es als Kulturkampfdebatte bis in den Reichsrat. Für Christlichsoziale war es ein „Kampf des freissinnigen Judentums gegen das Christentum“ in dem sich „Zionisten, deutsche Kulturkämpfer, tschechische und ruthenische Radikale“ in einer „internationalen Koalition“ als „freisinniger Ring des jüdischen Radikalismus und des radikalen Slawentums“ präsentierten. Wahrmund hingegen bezeichnete in der allgemein aufgeheizten Stimmung katholische Studenten als „Verräter und Parasiten“. Als Wahrmund 1908 eine seiner Reden, in der er Gott, die christliche Moral und die katholische Heiligenverehrung anzweifelte, in Druck bringen ließ, erhielt er eine Anzeige wegen Gotteslästerung. Nach weiteren teils gewalttätigen Versammlungen sowohl auf konservativer und antiklerikaler Seite, studentischen Ausschreitungen und Streiks musste kurzzeitig sogar der Unibetrieb eingestellt werden. Wahrmund wurde zuerst beurlaubt, später an die deutsche Universität Prag versetzt.

Auch in der Ersten Republik war die Verbindung zwischen Kirche und Staat stark. Der christlichsoziale, als Eiserner Prälat in die Geschichte eingegangen Ignaz Seipel schaffte es in den 1920er Jahren bis ins höchste Amt des Staates. Bundeskanzler Engelbert Dollfuß sah seinen Ständestaat als Konstrukt auf katholischer Basis als Bollwerk gegen den Sozialismus. Auch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg waren Kirche und Politik in Person von Bischof Rusch und Kanzler Wallnöfer ein Gespann. Erst dann begann eine ernsthafte Trennung. Glaube und Kirche haben noch immer ihren fixen Platz im Alltag der Innsbrucker, wenn auch oft unbemerkt. Die Kirchenaustritte der letzten Jahrzehnte haben der offiziellen Mitgliederzahl zwar eine Delle versetzt und Freizeitevents werden besser besucht als Sonntagsmessen. Die römisch-katholische Kirche besitzt aber noch immer viel Grund in und rund um Innsbruck, auch außerhalb der Mauern der jeweiligen Klöster und Ausbildungsstätten. Etliche Schulen in und rund um Innsbruck stehen ebenfalls unter dem Einfluss konservativer Kräfte und der Kirche. Und wer immer einen freien Feiertag genießt, ein Osterei ans andere peckt oder eine Kerze am Christbaum anzündet, muss nicht Christ sein, um als Tradition getarnt im Namen Jesu zu handeln.

The Teutonic Order & Maximilian III.

Maximilian the German master (1558 - 1618) officially took up his post as Gubernator of Tyrol and Vorderösterreich in 1602. Unlike his predecessors, he was the administrator of the land and not its owner. This was reflected in his demeanour. He was a pious and deeply religious man who had to reconcile Christian charity with the political office of regent in a peculiar way. He regularly withdrew for long periods into the seclusion of his study in the Capuchin monastery, founded in 1594, in order to live there in the most modest and austere conditions. He did not organise any lavish parties. He cut Ferdinand's bloated court almost in half. Under Maximilian, strict customs were introduced in Innsbruck. According to legend, children were forbidden to play in the streets. As a fervent representative of the Counter-Reformation, the enforcement of the Catholic faith was of particular concern to him. Unlike his predecessors, he wanted to achieve this through moral rigour rather than ostentatious building projects. He limited himself to completing churches that had already been started, such as the Servite Church or the Jesuit Church, instead of burdening the Tyrolean treasury with new projects. The Innsbruck district of St Nicholas was given its own parish priest, who watched over the salvation of the less well-off but all the more hard-working subjects. Maximilian did not organise lavish concerts in theatres, but together with the widow of his predecessor, Anna Katharina Gonzaga, promoted church singing. Nativity scenes and Easter graves began to establish themselves as an expression of popular faith. Whether it was his example as a pious sovereign, his moderate and prudent religious policy or counter-reformatory suppression, Protestant ideas died a quiet death in the Holy Land of Tyrol under Maximilian's reign, while they continued to simmer in many German principalities.

However, his piety did not exclude scientific interest and the practical measures derived from it for the good of the city. The 17th century was a time when open-minded aristocrats turned to alchemists to replenish the state coffers and had horoscopes cast by scientists such as Johannes Keppler, while they violently campaigned against the "heresy" of the Protestants. The Jesuit, physicist and astronomer Christoph Scheiner, one of the discoverers of sunspots alongside Galileo Galilei, spent three years at Maximilian's court in Innsbruck and researched the function of the human eye at the Inn. Maximilian had him set up a telescope and carried out astronomical research together with Scheiner. Educational institutions also benefited from him. During his reign, the Jesuits expanded their educational mission to include the study of theology and dialectics, which was the first step towards a university.

However, the beginning of the Enlightenment was not just a matter for the princely study room, but was also reflected in the everyday life of the citizens of Innsbruck. The city's fire-fighting system and the hygiene of the Ritschenwhich served as a sewerage system and water source within the city walls, were improved under Maximilian according to the latest knowledge of the time. The second measure in particular was intended to protect the city from a repeat of the great catastrophe under Maximilian's aegis. During his reign, he had to deal with the outbreak of a plague epidemic. The Dreiheiligenkirche church in Kohlstatt, the working-class neighbourhood of the early modern period near the Zeughaus, was built under his patronage to ensure heavenly patronage as well as protection through better hygiene.

The year of Maximilian's death in 1618 marked the beginning of the Thirty Years' War in Europe. As boring as his pious and peaceful reign without ostentation and drama may seem today, the years of peace were probably a blessing for his contemporaries. The moralising Habsburg took the thankless middle seat between the eccentrics Ferdinand II and Leopold V and could hardly leave his mark on the city's memory. Alongside the Dreiheiligenkirche, his final resting place is his most conspicuous legacy. Maximilian's tomb in Innsbruck Cathedral is one of the most remarkable tombs of the Baroque period.

It also tells the interesting story of the Teutonic Order. Maximilian was not only Gubernator of Tyrol and Vorderösterreich, but also Archduke of Austria, Administrator of Prussia and Grand Master of the Teutonic Order. Another Grand Master of the Teutonic Order from the House of Habsburg with a connection to Innsbruck is also buried next to him. Archduke Eugene was the supreme commander of the Austro-Hungarian army on the Italian front during the First World War. The German Orders vividly illustrates the theological mindset and the connection between pious faith and secular power in the early modern period. In the period up to 1500, devout piety and the fear of God were often combined with the exercise of secular power. The order was founded as an order of knights in Jerusalem around 1120 as part of the Crusades. Church and chivalry united to enable pilgrims to visit the holy cities, especially the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, without danger. After the expulsion from Palestine, the knights of the Teutonic Order became involved on the side of Christian Magyars in Transylvania in what is now Romania against pagan tribes. In the 13th century, the Order under Hermann von Salza was able to gain a lot of land in the Baltic region in the fight against the pagan Prussians and conquer the Teutonic Order state establish. This brotherhood acted as a kind of state that, like religious fundamentalists today, invoked God and wanted to establish his order on earth. It was ideals such as Christian charity and the protection of the poor and helpless that also characterised the Teutonic Order at its core. This made it an ideal fit for the Habsburg dynasty. After the decline of the Order in north-east Europe in the 15th century, the Order retained its possessions and power through skilful liaison with the nobility and the military, particularly in the Habsburg Empire.

The Red Bishop and Innsbruck's moral decay

In the 1950s, Innsbruck began to recover from the crisis and war years of the first half of the 20th century. On 15 May 1955, Federal Chancellor Leopold Figl declared with the famous words "Austria is free" and the signing of the State Treaty officially marked the political turning point. In many households, the "political turnaround" became established in the years known as Economic miracle moderate prosperity. Between 1953 and 1962, annual economic growth of over 6% allowed an increasing proportion of the population to dream of things that had long been exotic, such as refrigerators, their own bathroom or even a holiday in the south. This period brought not only material but also social change. People's desires became more outlandish with increasing prosperity and the lifestyle conveyed in advertising and the media. The phenomenon of a new youth culture began to spread gently amidst the grey society of small post-war Austria. The terms Teenager and "latchkey kid" entered the Austrian language in the 1950s. The big world came to Innsbruck via films. Cinema screenings and cinemas had already existed in Innsbruck at the turn of the century, but in the post-war period the programme was adapted to a young audience for the first time. Hardly anyone had a television set in their living room and the programme was meagre. The numerous cinemas courted the public's favour with scandalous films. From 1956, the magazine BRAVO. For the first time, there was a medium that was orientated towards the interests of young people. The first issue featured Marylin Monroe, with the question: „Marylin's curves also got married?“ The big stars of the early years were James Dean and Peter Kraus, before the Beatles took over in the 60s. After the Summer of Love Dr Sommer explained about love and sex. The church's omnipotent authority over the moral behaviour of adolescents began to crumble, albeit only slowly. The first photo love story with bare breasts did not follow until 1982. Until the 1970s, the opportunities for adolescent Innsbruckers were largely limited to pub parlours, shooting clubs and brass bands. Only gradually did bars, discos, nightclubs, pubs and event venues open. Events such as the 5 o'clock tea dance at the Sporthotel Igls attracted young people looking for a mate. The Cafe Central became the „second home of long-haired teenagers“, as the Tiroler Tageszeitung newspaper stated with horror in 1972. Establishments like the Falconry cellar in the Gilmstraße, the Uptown Jazzsalon in Hötting, the jazz club in the Hofgasse, the Clima Club in Saggen, the Scotch Club in the Angerzellgasse and the Tangent in Bruneckerstraße had nothing in common with the traditional Tyrolean beer and wine bar. The performances by the Rolling Stones and Deep Purple in the Olympic Hall in 1973 were the high point of Innsbruck's spring awakening for the time being. Innsbruck may not have become London or San Francisco, but it had at least breathed a breath of rock'n'roll. What is still anchored in cultural memory today as the '68 movement took place in the Holy Land hardly took place. Neither workers nor students took to the barricades in droves. The historian Fritz Keller described the „68 movement in Austria as "Mail fan“. Nevertheless, society was quietly and secretly changing. A look at the annual charts gives an indication of this. In 1964, it was still Chaplain Alfred Flury and Freddy with „Leave the little things“ and „Give me your word" and the Beatles with their German version of "Come, give me your hand who dominated the Top 10, musical tastes changed in the years leading up to the 1970s. Peter Alexander and Mireille Mathieu were still to be found in the charts. From 1967, however, it was international bands with foreign-language lyrics such as The Rolling Stones, Tom Jones, The Monkees, Scott McKenzie, Adriano Celentano or Simon and Garfunkel, who occupied the top positions in great density with partly socially critical lyrics.

This change provoked a backlash. The spearhead of the conservative counter-revolution was the Innsbruck bishop Paulus Rusch. Cigarettes, alcohol, overly permissive fashion, holidays abroad, working women, nightclubs, premarital sex, the 40-hour week, Sunday sporting events, dance evenings, mixed sexes in school and leisure - all of these things were strictly abhorrent to the strict churchman and follower of the Sacred Heart cult. Peter Paul Rusch was born in Munich in 1903 and grew up in Vorarlberg as the youngest of three children in a middle-class household. Both parents and his older sister died of tuberculosis before he reached adulthood. At the young age of 17, Rusch had to fend for himself early on in the meagre post-war period. Inflation had eaten up his father's inheritance, which could have financed his studies, in no time at all. Rusch worked for six years at the Bank for Tyrol and Vorarlberg, in order to finance his theological studies. He entered the Collegium Canisianum in 1927 and was ordained a priest of the Jesuit order six years later. His stellar career took the intelligent young man first to Lech and Hohenems as chaplain and then back to Innsbruck as head of the seminary. In 1938, he became titular bishop of Lykopolis and Apostolic Administrator for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. As the youngest bishop in Europe, he had to survive the harassment of the church by the National Socialist rulers. Although his critical attitude towards National Socialism was well known, Rusch himself was never imprisoned. Those in power were too afraid of turning the popular young bishop into a martyr.

After the war, the socially and politically committed bishop was at the forefront of reconstruction efforts. He wanted the church to have more influence on people's everyday lives again. His father had worked his way up from carpenter to architect and probably gave him a soft spot for the building industry. He also had his own experience at BTV. Thanks to his training as a banker, Rusch recognised the opportunities for the church to get involved and make a name for itself as a helper in times of need. It was not only the churches that had been damaged in the war that were rebuilt. The Catholic Youth under Rusch's leadership, was involved free of charge in the construction of the Heiligjahrsiedlung in the Höttinger Au. The diocese bought a building plot from the Ursuline order for this purpose. The loans for the settlers were advanced interest-free by the church. Decades later, his rustic approach to the housing issue would earn him the title of "Red Bishop" to the new home. In the modest little houses with self-catering gardens, in line with the ideas of the dogmatic and frugal "working-class bishop", 41 families, preferably with many children, found a new home.

By alleviating the housing shortage, the greatest threats in the Cold WarCommunism and socialism, from his community. The atheism prescribed by communism and the consumer-orientated capitalism that had swept into Western Europe from the USA after the war were anathema to him. In 1953, Rusch's book "Young worker, where to?". What sounds like revolutionary, left-wing reading from the Kremlin showed the principles of Christian social teaching, which castigated both capitalism and socialism. Families should live modestly in order to live in Christian harmony with the moderate financial means of a single father. Entrepreneurs, employees and workers were to form a peaceful unity. Co-operation instead of class warfare, the basis of today's social partnership. To each his own place in a Christian sense, a kind of modern feudal system that was already planned for use in Dollfuß's corporative state. He shared his political views with Governor Eduard Wallnöfer and Mayor Alois Lugger, who, together with the bishop, organised the Holy Trinity of conservative Tyrol at the time of the economic miracle. Rusch combined this with a latent Catholic anti-Semitism that was still widespread in Tyrol after 1945 and which, thanks to aberrations such as the veneration of the Anderle von Rinn has long been a tradition.

Education and training were of particular concern to the pugnacious Jesuit. The social formation across all classes by the soldiers of Christ could look back on a long tradition in Innsbruck. In 1909, the Jesuit priest and former prison chaplain Alois Mathiowitz (1853 - 1922) founded the Peter-Mayr-Bund. His approach was to put young people on the right path through leisure activities and sport and adults from working-class backgrounds through lectures and popular education. The workers' youth centre in Reichenauerstraße, which was built under his aegis, still serves as a youth centre and kindergarten today. Rusch also had experience with young people. In 1936, he was elected regional field master of the scouts in Vorarlberg. Despite a speech impediment, he was a charismatic guy and extremely popular with his young colleagues and teenagers. In his opinion, only a sound education under the wing of the church according to the Christian model could save the salvation of young people. In order to give young people a perspective and steer them in an orderly direction with a home and family, the Youth building society savings strengthened. In the parishes, kindergartens, youth centres and educational institutions such as the House of encounter on Rennweg in order to have education in the hands of the church right from the start. The vast majority of the social life of the city's young people did not take place in disreputable dive bars. Most young people simply didn't have the money to go out regularly. Many found their place in the more or less orderly channels of Catholic youth organisations. Alongside the ultra-conservative Bishop Rusch, a generation of liberal clerics grew up who became involved in youth work. In the 1960s and 70s, two church youth movements with great influence were active in Innsbruck. Sigmund Kripp and Meinrad Schumacher were responsible for this, who were able to win over teenagers and young adults with new approaches to education and a more open approach to sensitive topics such as sexuality and drugs. The education of the elite in the spirit of the Jesuit order was provided in Innsbruck from 1578 by the Marian Congregation. This youth organisation, still known today as the MK, took care of secondary school pupils. The MK had a strict hierarchical structure in order to give the young Soldaten Christi obedience from the very beginning. In 1959, Father Sigmund Kripp took over the leadership of the organisation. Under his leadership, the young people, with financial support from the church, state and parents and with a great deal of personal effort, set up projects such as the Mittergrathütte including its own material cable car in Kühtai and the legendary youth centre Kennedy House in the Sillgasse. Chancellor Klaus and members of the American embassy were present at the laying of the foundation stone for this youth centre, which was to become the largest of its kind in Europe with almost 1,500 members, as the building was dedicated to the first Catholic president of the USA, who had only recently been assassinated.

The other church youth organisation in Innsbruck was Z6. The city's youth chaplain, Chaplain Meinrad Schumacher, took care of the youth organisation as part of the Action 4-5-6 to all young people who are in the MK or the Catholic Student Union had no place. Working-class children and apprentices met in various youth centres such as Pradl or Reichenau before the new centre, also built by the members themselves, was opened at Zollerstraße 6 in 1971. Josef Windischer took over the management of the centre. The Z6 already had more to do with what Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda were doing on the big screen on their motorbikes in Easy Rider was shown. Things were rougher here than in the MK. Rock gangs like the Santanas, petty criminals and drug addicts also spent their free time in Z6. While Schumacher reeled off his programme upstairs with the "good" youngsters, Windischer and the Outsiders the basement to help the lost sheep as much as possible.

At the end of the 1960s, both the MK and the Z6 decided to open up to non-members. Girls' and boys' groups were partially merged and non-members were also admitted. Although the two youth centres had different target groups, the concept was the same. Theological knowledge and Christian morals were taught in a playful, age-appropriate environment. Sections such as chess, football, hockey, basketball, music, cinema films and a party room catered to the young people's needs for games, sport and the removal of taboos surrounding their first sexual experiences. The youth centres offered a space where young people of both sexes could meet. However, the MK in particular remained an institution that had nothing to do with the wild life of the '68ers, as it is often portrayed in films. For example, dance courses did not take place during Advent, carnival or on Saturdays, and for under-17s they were forbidden.

Nevertheless, the youth centres went too far for Bishop Rusch. The critical articles in the MK newspaper We discuss, which reached a circulation of over 2,000 copies, found less and less favour. Solidarity with Vietnam was one thing, but criticism of marksmen and the army could not be tolerated. After years of disputes between the bishop and the youth centre, it came to a showdown in 1973. When Father Kripp published his book Farewell to tomorrow in which he reported on his pedagogical concept and the work in the MK, there were non-public proceedings within the diocese and the Jesuit order against the director of the youth centre. Despite massive protests from parents and members, Kripp was removed. Neither the intervention within the church by the eminent theologian Karl Rahner, nor a petition initiated by the artist Paul Flora, nor regional and national outrage in the press could save the overly liberal Father from the wrath of Rusch, who even secured the papal blessing from Rome for his removal from office.

In July 1974, the Z6 was also temporarily over. Articles about the contraceptive pill and the Z6 newspaper's criticism of the Catholic Church were too much for the strict bishop. Rusch had the keys to the youth centre changed without further ado, a method he also used at the Catholic Student Union when it got too close to a left-wing action group. The Tiroler Tageszeitung noted this in a small article on 1 August 1974:

"In recent weeks, there had been profound disputes between the educators and the bishop over fundamental issues. According to the bishop, the views expressed in "Z 6" were "no longer in line with church teaching". For example, the leadership of the centre granted young people absolute freedom of conscience without simultaneously recognising objective norms and also permitted sexual relations before marriage."

It was his adherence to conservative values and his stubbornness that damaged Rusch's reputation in the last 20 years of his life. When he was consecrated as the first bishop of the newly founded diocese of Innsbruck in 1964, times were changing. The progressive with practical life experience of the past was overtaken by the modern life of a new generation and the needs of the emerging consumer society. The bishop's constant criticism of the lifestyle of his flock and his stubborn adherence to his overly conservative values, coupled with some bizarre statements, turned the co-founder of development aid into a Brother in needthe young, hands-on bishop of the reconstruction, from the late 1960s onwards as a reason for leaving the church. His concept of repentance and penance took on bizarre forms. He demanded guilt and atonement from the Tyroleans for their misdemeanours during the Nazi era, but at the same time described the denazification laws as too far-reaching and strict. In response to the new sexual practices and abortion laws under Chancellor Kreisky, he said that girls and young women who have premature sexual intercourse are up to twelve times more likely to develop cancer of the mother's organs. Rusch described Hamburg as a cesspool of sin and he suspected that the simple minds of the Tyrolean population were not up to phenomena such as tourism and nightclubs and were tempted to immoral behaviour. He feared that technology and progress were making people too independent of God. He was strictly against the new custom of double income. People should be satisfied with a spiritual family home with a vegetable garden and not strive for more; women should concentrate on their traditional role as housewife and mother.

In 1973, after 35 years at the head of the church community in Tyrol and Innsbruck, Bishop Rusch was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck. He resigned from his office in 1981. In 1986, Innsbruck's first bishop was laid to rest in St Jakob's Cathedral. The Bishop Paul's Student Residence The church of St Peter Canisius in the Höttinger Au, which was built under him, commemorates him.

After its closure in 1974, the Z6 youth centre moved to Andreas-Hofer-Straße 11 before finding its current home in Dreiheiligenstraße, in the middle of the working-class district of the early modern period opposite the Pest Church. Jussuf Windischer remained in Innsbruck after working on social projects in Brazil. The father of four children continued to work with socially marginalised groups, was a lecturer at the Social Academy, prison chaplain and director of the Caritas Integration House in Innsbruck.

The MK also still exists today, even though the Kennedy House, which was converted into a Sigmund Kripp House was renamed, no longer exists. In 2005, Kripp was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck by his former sodalist and later deputy mayor, like Bishop Rusch before him.

Air raids on Innsbruck

Wie der Lauf der Geschichte der Stadt unterliegt auch ihr Aussehen einem ständigen Wandel. Besonders gut sichtbare Veränderungen im Stadtbild erzeugten die Jahre rund um 1500 und zwischen 1850 bis 1900, als sich politische, wirtschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Veränderungen in besonders schnellem Tempo abspielten. Das einschneidendste Ereignis mit den größten Auswirkungen auf das Stadtbild waren aber wohl die Luftangriffe auf die Stadt im Zweiten Weltkrieg, als aus der „Heimatfront“ der Nationalsozialisten ein tatsächlicher Kriegsschauplatz wurde. Die Lage am Fuße des Brenners war über Jahrhunderte ein Segen für die Stadt gewesen, nun wurde sie zum Verhängnis. Innsbruck war ein wichtiger Versorgungsbahnhof für den Nachschub an der Italienfront. In der Nacht vom 15. auf den 16. Dezember 1943 erfolgte der erste alliierte Luftangriff auf die schlecht vorbereitete Stadt. 269 Menschen fielen den Bomben zum Opfer, 500 wurden verletzt und mehr als 1500 obdachlos. Über 300 Gebäude, vor allem in Wilten und der Innenstadt, wurden zerstört und beschädigt. Am Montag, den 18. Dezember fanden sich in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten, dem Vorgänger der Tiroler Tageszeitung, auf der Titelseite allerhand propagandistische Meldungen vom erfolgreichen und heroischen Abwehrkampf der Deutschen Wehrmacht an allen Fronten gegenüber dem Bündnis aus Anglo-Amerikanern und dem Russen, nicht aber vom Bombenangriff auf Innsbruck.

Bombenterror über Innsbruck

Innsbruck, 17. Dez. Der 16. Dezember wird in der Geschichte Innsbrucks als der Tag vermerkt bleiben, an dem der Luftterror der Anglo-Amerikaner die Gauhauptstadt mit der ganzen Schwere dieser gemeinen und brutalen Kampfweise, die man nicht mehr Kriegführung nennen kann, getroffen hat. In mehreren Wellen flogen feindliche Kampfverbände die Stadt an und richteten ihre Angriffe mit zahlreichen Spreng- und Brandbomben gegen die Wohngebiete. Schwerste Schäden an Wohngebäuden, an Krankenhäusern und anderen Gemeinschaftseinrichtungen waren das traurige, alle bisherigen Schäden übersteigende Ergebnis dieses verbrecherischen Überfalles, der über zahlreiche Familien unserer Stadt schwerste Leiden und empfindliche Belastung der Lebensführung, das bittere Los der Vernichtung liebgewordenen Besitzes, der Zerstörung von Heim und Herd und der Heimatlosigkeit gebracht hat. Grenzenloser Haß und das glühende Verlangen diese unmenschliche Untat mit schonungsloser Schärfe zu vergelten, sind die einzige Empfindung, die außer der Auseinandersetzung mit den eigenen und den Gemeinschaftssorgen alle Gemüter bewegt. Wir alle blicken voll Vertrauen auf unsere Soldaten und erwarten mit Zuversicht den Tag, an dem der Führer den Befehl geben wird, ihre geballte Kraft mit neuen Waffen gegen den Feind im Westen einzusetzen, der durch seinen Mord- und Brandterror gegen Wehrlose neuerdings bewiesen hat, daß er sich von den asiatischen Bestien im Osten durch nichts unterscheidet – es wäre denn durch größere Feigheit. Die Luftschutzeinrichtungen der Stadt haben sich ebenso bewährt, wie die Luftschutzdisziplin der Bevölkerung. Bis zur Stunde sind 26 Gefallene gemeldet, deren Zahl sich aller Voraussicht nach nicht wesentlich erhöhen dürfte. Die Hilfsmaßnahmen haben unter Führung der Partei und tatkräftigen Mitarbeit der Wehrmacht sofort und wirkungsvoll eingesetzt.

Diese durch Zensur und Gleichschaltung der Medien fantasievoll gestaltete Nachricht schaffte es gerade mal auf Seite 3. Prominenter wollte man die schlechte Vorbereitung der Stadt auf das absehbare Bombardement wohl nicht dem Volkskörper präsentieren. Ganz so groß wie 1938 nach dem Anschluss, als Hitler am 5. April von 100.000 Menschen in Innsbruck begeistert empfangen worden war, war die Begeisterung für den Nationalsozialismus nicht mehr. Zu groß waren die Schäden an der Stadt und die persönlichen, tragischen Verluste in der Bevölkerung. Dass die sterblichen Überreste der Opfer des Luftangriffes vom 15. Dezember 1943 am heutigen Landhausplatz vor dem neu errichteten Gauhaus als Symbol nationalsozialistischer Macht im Stadtbild aufgebahrt wurden, zeugt von trauriger Ironie des Schicksals.

Im Jänner 1944 begann man Luftschutzstollen und andere Schutzmaßnahmen zu errichten. Die Arbeiten wurden zu einem großen Teil von Gefangenen des Konzentrationslagers Reichenau durchgeführt. Insgesamt wurde Innsbruck zwischen 1943 und 1945 zweiundzwanzig Mal angegriffen. Dabei wurden knapp 3833, also knapp 50%, der Gebäude in der Stadt beschädigt und 504 Menschen starben. In den letzten Kriegsmonaten war an Normalität nicht mehr zu denken. Die Bevölkerung lebte in dauerhafter Angst. Die Schulen wurden bereits vormittags geschlossen. An einen geregelten Alltag war nicht mehr zu denken. Die Stadt wurde zum Glück nur Opfer gezielter Angriffe. Deutsche Städte wie Hamburg oder Dresden wurden von den Alliierten mit Feuerstürmen mit Zehntausenden Toten innerhalb weniger Stunden komplett dem Erdboden gleichgemacht. Viele Gebäude wie die Jesuitenkirche, das Stift Wilten, die Servitenkirche, der Dom, das Hallenbad in der Amraserstraße wurden getroffen. Besondere Behandlung erfuhren während der Angriffe historische Gebäude und Denkmäler. Das Goldene Dachl was protected with a special construction, as was Maximilian's sarcophagus in the Hofkirche. The figures in the Hofkirche, the Schwarzen Mannder, wurden nach Kundl gebracht. Die Madonna Lucas Cranachs aus dem Innsbrucker Dom wurde während des Krieges ins Ötztal überführt.

Der Luftschutzstollen südlich von Innsbruck an der Brennerstraße und die Kennzeichnungen von Häusern mit Luftschutzkellern mit ihren schwarzen Vierecken und den weißen Kreisen und Pfeilen kann man heute noch begutachten. Zwei der Stellungen der Flugabwehrgeschütze, mittlerweile nur noch zugewachsene Mauerreste, können am Lanser Köpfl oberhalb von Innsbruck besichtigt werden. In Pradl, wo neben Wilten die meisten Gebäude beschädigt wurden, weisen an den betroffenen Häusern Bronzetafeln mit dem Hinweis auf den Wiederaufbau auf einen Bombentreffer hin.