Hungerburgbahn & Nordkettenbahn

New Hungerburgbahn: Kongresshaus valley station

Old Hungerburg railway: Rennweg 39

Worth knowing

Innsbruck calls itself the capital of the Alps. The highest point within the city limits is the peak of the Praxmarerkarspitze at 2,642 meters above sea level. One may debate the title of “capital”—Grenoble, Turin, Trento, Bern and many other cities could certainly claim it for themselves. But Innsbruck holds a special place in this ranking thanks to its enclosed position between the surrounding mountains and the direct connection between the city and its alpine environment. As early as around 1900, efforts began to develop the Nordkette with technical means. The first funicular railways in Europe began operating around 1880. With some delay, Innsbruck was also to receive its own example. It was Josef Riehl, tourism and transport pioneer, who recognized the potential of linking the city with the mountains. Along with the Panorama Building and the old chain bridge, the railway to Hungerburg formed the modern center of Innsbruck at the beginning of the 20th century. The three attractions were united not only by their legendary locations but also by their premature endings. The old, majestic chain bridge was replaced by a more modern reinforced concrete bridge in 1939, and the Panorama Building has stood empty since 2011. Finally, in 2005, the Hungerburgbahn also met its end. Despite several appeals from the public, operations were shut down. Only the steel truss bridge over the Inn and the rammed concrete viaduct in the upper section of the line were preserved. 101 years earlier, the new transport link—planned as a connection between Innsbruck and the newly developing district—had been the number one topic in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten:

„The Hungerburgbahn opened this morning at 7 a.m. - not exactly favoured by the best weather. Trains run every quarter of an hour until 10 o'clock in the evening. It seems that the local population is particularly interested in the new railway, which is the first cable car in North Tyrol. Yesterday, an internal evening at the Hotel Mariabrunn brought together representatives of the company, the construction management, the "Union", the municipal power station and the press for a cheerful get-together. Engineer Innerebner commemorated the creator of the railway, Mr Riehl, who is currently taking a cure in Karlovy Vary ... Works inspector Twerdy has taken over the management of the plant. Six and a half years ago, he only took over the local railway Innsbruck - Hall; since then, he has taken over four railways of all systems: the low mountain railway, the Stubai valley railway, the electric tramway and now the cable railway to the Hungerburg.“

The aerial cableway to the Nordkette, starting from the Hungerburg, opened in 1928—the same year as the mountain railway on the southern side of the Inn Valley, the Patscherkofelbahn. Innsbruck was not avant-garde in this respect; the world’s first cable car had begun operating only 20 years earlier in Grindelwald, Switzerland. But Innsbruck was certainly keeping up with the times. The breathtaking project in the Tyrolean capital included the valley station on the Hungerburg, the mid-station on the Seegrube, and the top station at the Hafelekar in the high-alpine region. Much of the construction work on these high-alpine projects was still carried out by porters who hauled materials up the mountain. Only for particularly exposed areas were aircraft used. Despite this, construction took just over a year. The marvel was designed by the previously unknown Franz Baumann, who won a design competition with his bold concept. He rejected the prevailing styles of the 19th century—classicist, traditional, and historicist trends. The buildings should blend into the landscape and become part of it rather than disturb it. Baumann managed to harmoniously connect the functional station buildings with machine rooms and entry/exit zones with the gastronomic areas. The mid-station on the Seegrube housed a restaurant and hotel. He placed great emphasis on the terrace, which offers a breathtaking view of the surrounding mountains. Particularly spectacular is the top station at the Hafelekar, perched like an eagle’s nest against the rocks and shaped as a quarter circle, housing a guesthouse. Baumann designed both the buildings and the interior. Traditional alpine hospitality with tiled stoves met modern furnishings such as the now-famous Baumann chair. He even designed his own typeface to ensure a cohesive overall impression. Clemens Holzmeister, the internationally best-known architect of Tyrolean Modernism, declared himself a fan of the Nordkette cableway in a 1929 specialist article:

"The railway starts at the so-called Hungerburg plateau (300 metres above Innsbruck). The station is characterised by its simple integration into the forest area and a particularly remarkable staircase. The intermediate station at Seegrube (1905 metres above sea level) lacks the unity of the layout ... due to subsequent extensions, but appears splendidly positioned in front of the rocky cirque of the Seegrube peaks. The final station (2,256 metres above sea level) is the most successful in its integration into the wild Zipfelschrofen. Everything has been taken into consideration and the naturalness has a liberating effect."

Since 1979, the Innsbruck Public Transport Company (IVB) has operated the mountain railway. During renovations in 2007, both the interiors and exteriors of the mid- and top stations were preserved as much as possible. Today, one can board the Nordkettenbahn directly at the Congress Center in the heart of the city and reach the Hafelekar at 2,256 meters in just a short time. The stations of the new line at the Löwenhaus, the Alpine Zoo, and the Hungerburg were designed by star architect Zaha Hadid in a breathtaking futuristic style.

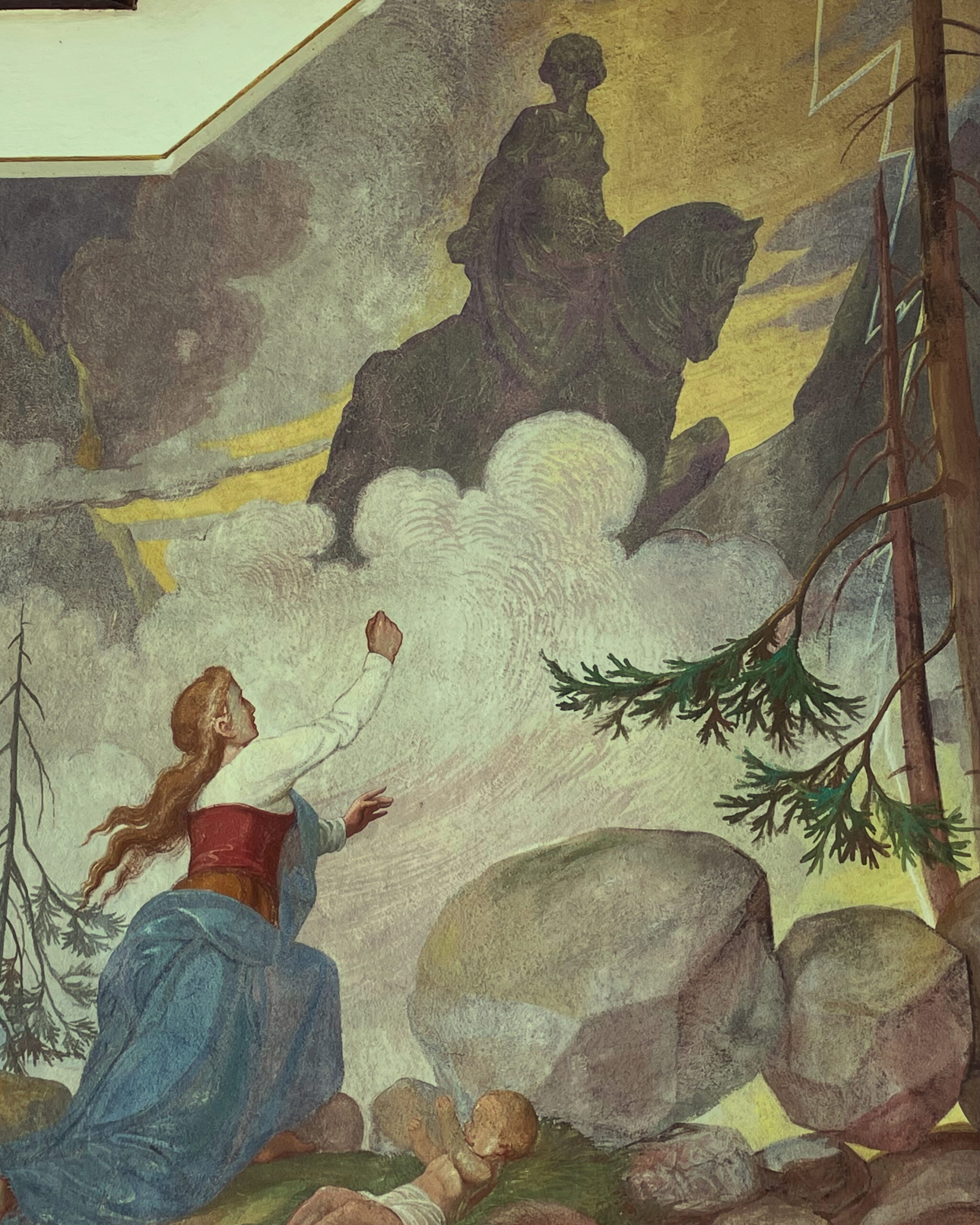

But the Nordkette is more than an adventure park for locals and tourists. In the 1930s, scientific history was made there. In 1931, Victor Franz Hess established a laboratory in a former construction barrack at the Hafelekar at 2,300 meters to study cosmic radiation. For this work, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1936. Less scientific, but of great educational value, the mountains continue to enter children’s rooms to this day. On the western side of the Nordkette (from the city, on the left), a distinctive rocky peak rises. With some imagination, the formation resembles a woman on a horse. This figure is the inspiration for the most famous legend of the Innsbruck area, which entered the Grimm Brothers’ catalog of tales in the 19th century. It tells the story of the stingy, hard-hearted, and greedy giant queen Frau Hitt. While playing, her son fell into a bog with his expensive clothes and returned home covered in filth. Frau Hitt ordered a servant to bathe the boy in milk and clean him with white bread. Later, the queen encountered a beggar who pleaded for bread. Instead of alms, Frau Hitt handed her a stone. When she refused charity, an earthquake destroyed her palace, a landslide buried her lands, and Frau Hitt was turned into the stone pillar that still towers visibly above the city today. Innsbruck children have grown up with this legend—its moral warning against arrogance and wastefulness—for generations.

Franz Baumann and Tyrolean modernism

The First World War not only brought ruling dynasties and empires to an end, the 1920s also saw many changes in art, music, literature and architecture. While jazz, atonal music and expressionism failed to establish themselves in little Innsbruck, a handful of architects changed the cityscape in an astonishing way. Inspired by new forms of design such as the Bauhaus style, skyscrapers from the USA and the Soviet Modernism from the revolutionary USSR, sensational projects emerged in Innsbruck. The best-known representatives of the avant-garde who brought about this new way of designing public space in Tyrol were Lois Welzenbacher, Siegfried Mazagg, Theodor Prachensky and Clemens Holzmeister. Each of these architects had their own idiosyncrasies, making the Tiroler Moderne nur schwer eindeutig zu definieren ist. Allen gemeinsam war die Abwendung von der klassizistischen Architektur der Vorkriegszeit unter gleichzeitiger Beibehaltung typischer alpiner Materialien und Elemente unter dem Motto Form follows function. Lois Welzenbacher schrieb 1920 in einem Artikel der Zeitschrift Tyrolean highlands about the architecture of this period:

"As far as we can judge today, it is clear that the 19th century lacked the strength to create its own distinct style. It is the age of stillness... Thus details were reproduced with historical accuracy, mostly without any particular meaning or purpose, and without a harmonious overall picture that would have arisen from factual or artistic necessity."

The best-known and most impressive representative of the so-called Tiroler Moderne was Franz Baumann (1892 - 1974). Unlike Holzmeister or Welzenbacher, he had no academic training. Baumann was born in Innsbruck in 1892, the son of a postal clerk. The theologian, publicist and war propagandist Anton Müllner, alias Bruder Willram became aware of Franz Baumann's talent as a draughtsman and enabled the young man to attend the Staatsgewerbeschule, today's HTL, at the age of 14. It was here that he met his future brother-in-law Theodor Prachensky. Together with Baumann's sister Maria, the two young men went on excursions in the area around Innsbruck to paint pictures of the mountains and nature. During his school years, he gained his first professional experience as a bricklayer at the construction company Huter & Söhne. In 1910 Baumann followed his friend Prachensky to Merano to work for the company Musch & Lun zu arbeiten. Meran war damals Tirols wichtigster Tourismusort mit internationalen Kurgästen. Unter dem Architekten Adalbert Erlebach machte er erste Erfahrungen bei der Planung von Großprojekten wie Hotels und Seilbahnen. Wie den Großteil seiner Generation riss der Erste Weltkrieg auch Baumann aus Berufsleben und Alltag. An der Italienfront erlitt er im Kampfeinsatz einen Bauchschuss, von dem er sich in einem Lazarett in Prag erholte. In dieser ansonsten tatenlosen Zeit malte er Stadtansichten von Bauwerken in und rund um Prag. Diese Bilder, die ihm später bei der Visualisierung seiner Pläne helfen sollten, wurden in seiner einzigen Ausstellung 1919 präsentiert.

Baumann's breakthrough came in the second half of the 1920s. He was able to win the tenders for the remodelling of the Weinhaus Happ in the old town and the Nordkettenbahn railway. In addition to his creativity and ability to think holistically, he was also able to harmonise his architectural approach with the legal situation and the modern requirements of tendering in the 1920s. Construction was a state matter, the Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association together with the district administration, was the final authority responsible for the assessment and authorisation of construction projects. During his time in Merano, Baumann was already involved with the Homeland Security Association came into contact with it. Kunibert Zimmeter had founded this association together with Gotthard Graf Trapp in the final years of the monarchy. In "Our Tyrol. A heritage book" he wrote:

"Let us look at the flattening of our private lives, our amusements, at the centre of which, significantly, is the cinema, at the literary ephemera of our newspaper reading, at the hopeless and costly excesses of fashion in the field of women's clothing, let us take a look at our homes with the miserable factory furniture and all the dreadful products of our so-called gallantry goods industry, Things that thousands of people work to produce, creating worthless bric-a-brac in the process, or let us look at our apartment blocks and villas with their cement façades simulating palaces, countless superfluous towers and gables, our hotels with their pompous façades, what a waste of the people's wealth, what an abundance of tastelessness we must find there."

The economic boom of the late 1920s saw the emergence of a new clientele and clientele that placed new demands on buildings and therefore on the construction industry. In many Tyrolean villages, hotels had replaced churches as the largest building in the townscape. The aristocratic distance from the mountains had given way to a bourgeois enthusiasm for sport. This called for new solutions at new heights. No more grand hotels were built at 1500 m for spa holidays, but a complete infrastructure for skiers in high alpine terrain such as the Nordkette. The Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association ensured that nature and townscape were protected from overly fashionable trends, excessive tourism and ugly industrial buildings. Building projects had to blend harmoniously, attractively and appropriately into the environment. Despite the social and artistic innovations of the time, architects had to keep the typical regional character in mind. This was precisely the strength of Baumann's approach to holistic building in the Tyrolean sense. All technical functions and details, the embedding of the buildings in the landscape, taking into account the topography and sunlight, played a role for him, who was not officially allowed to use the title of architect. He thus followed the "Rules for those who build in the mountains" by the architect Adolf Loos from 1913:

Don't build picturesquely. Leave such effects to the walls, the mountains and the sun. The man who dresses picturesquely is not picturesque, but a buffoon. The farmer does not dress picturesquely. But he is...

Pay attention to the forms in which the farmer builds. For they are ancestral wisdom, congealed substance. But seek out the reason for the mould. If advances in technology have made it possible to improve the mould, then this improvement should always be used. The flail will be replaced by the threshing machine."

Baumann designed even the smallest details, from the exterior lighting to the furniture, and integrated them into his overall concept of the Tiroler Moderne in.

From 1927, Baumann worked independently in his studio in Schöpfstraße in Wilten. He repeatedly came into contact with his brother-in-law and employee of the building authority, Theodor Prachensky. From 1929, the two of them worked together to design the building for the new Hötting secondary school on Fürstenweg. Although boys and girls still had to be planned separately in the traditional way, the building was otherwise completely in keeping with the style of the Neuen Sachlichkeit and the principle Light, air and sun.

In his heyday, he employed 14 people in his office. Thanks to his modern approach, which combined function, aesthetics and economical construction, he survived the economic crisis well. Only the 1000-mark barrier, die Hitler 1934 über Österreich verhängte, um die Republik finanziell in Bredouille zu bringen, brachte sein Architekturbüro wie die gesamte Wirtschaft in Probleme. Nicht nur die Arbeitslosenquote im Tourismus verdreifachte sich innerhalb kürzester Zeit, auch die Baubranche geriet in Schwierigkeiten. 1935 wurde Baumann zum Leiter der Zentralvereinigung für Architekten, nachdem er mit einer Ausnahmegenehmigung ausgestattet diesen Berufstitel endlich tragen durfte. Im gleichen Jahr plante er die Hörtnaglsiedlung in the west of the city.

After the Anschluss in 1938, he quickly joined the NSDAP. On the one hand, like his colleague Lois Welzenbacher, he was probably not averse to the ideas of National Socialism, but on the other he was able to further his career as chairman of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in Tyrol. In this position, he courageously opposed the destructive furore with which those in power wanted to change Innsbruck's cityscape, which did not correspond to his idea of urban planning. The mayor of Innsbruck, Egon Denz, wanted to remove the Triumphal Gate and St Anne's Column in order to make more room for traffic in Maria-Theresienstraße. The city centre was still a transit area from the Brenner Pass in the south to reach the main road to the east and west on today's Innrain. At the request of Gauleiter Franz Hofer, a statue of Adolf Hitler was to be erected in place of St Anne's Column. Hofer also wanted to have the church towers of the collegiate church blown up. Baumann's opinion on these plans was negative. When the matter made it to Albert Speer's desk, he agreed with him. From this point onwards, Baumann was no longer awarded any public projects by Gauleiter Hofer.

After being questioned as part of the denazification process, Baumann began working at the city building authority, probably on the recommendation of his brother-in-law Prachensky. Baumann was fully exonerated, among other things by a statement from the Abbot of Wilten, whose church towers he had saved, but his reputation as an architect could no longer be repaired. Moreover, his studio in Schöpfstraße had been destroyed by a bomb in 1944. In his post-war career, he was responsible for the renovation of buildings damaged by the war. Under his leadership, Boznerplatz with the Rudolfsbrunnen fountain was rebuilt as well as Burggraben and the new Stadtsäle (Note: today House of Music).

Franz Baumann died in 1974 and his paintings, sketches and drawings are highly sought-after and highly traded. Anyone who takes a close look at recent major projects such as the city library, the PEMA towers and many of Innsbruck's housing estates will recognise the approaches of the Tiroler Moderne rediscover even today.

The power of geography

What most visitors to Innsbruck notice first and foremost are the mountains that seem to encircle the city. The mountains are not only beautiful to look at, but have always influenced many things in the city. This starts with supposedly small things like the weather, as the writer and politician Beda Webers' view from days gone by proves:

""The warm wind or scirocco is a special phenomenon. It comes from the south, bounces off the northern mountains and falls with force into the valley. It likes to cause headaches, but it melts the winter snow quickly and promotes fertility immensely. This makes it possible to plant maize in Innsbruck""

This weather phenomenon may take its name from Scirocco and traffic was not yet a major problem in 1851. However, just like the Innsbruck car driver today, the blacksmith in the old town in 1450 and the legionnaire sent from central Italy to the Alps in 350 were certainly complaining about the warm downdraught, which seems to drive everyone crazy several times a month. In the past, people were happy about the warm air that melted the snow in the fields, whereas today's tourists moan about the apery ski slopes on the Seegrube.

The location between the Wipptal valley in the south and the Nordkette mountain range not only influences the frequency of migraines, but also the leisure activities of Innsbruck residents, as Weber also recognised. "The locals are characterised by their cheerfulness and charity, they especially love shore excursions in the beautiful season." One may talk about Kindness and benevolence der Innsbrucker streiten, Landausflüge in Form von Wanderung, Skitour oder Radfahren erfreuen sich auch heute noch großer Beliebtheit. Kein Wunder, Innsbruck ist von Bergen umgeben. Innerhalb weniger Minuten kann man von jedem Ort in der Stadt aus mitten im Wald stehen. Junge Menschen aus ganz Europa verbringen ihre Studienzeit zumindest zu einem Teil an der Universität Innsbruck, nicht nur wegen der hervorragenden Professoren und Einrichtungen, sondern auch um ihre Freizeit auf den Pisten, Mountainbikerouten und Wanderwegen zu verbringen, ohne auf urbanes Flair vermissen zu müssen. Das ist Fluch und Segen zugleich. Die Universität als großer Arbeitgeber und Ausbildungsort kurbelt die Wirtschaft an, gleichzeitig steigen durch auswärtige Studenten die Lebenserhaltungskosten in der Stadt, die zwischen den Bergen eingeklemmt nicht weiterwachsen kann.

Was heute als Einschränkung im räumlichen Wachstum verstanden werden kann, war einst der Grund für das Wachstum. Innsbruck hatte das große Glück, durch die nahen Berge an frisches Trinkwasser zu kommen. Im 15. Jahrhundert zapfte man die Nordkette an, um die Stadt mit Trinkwasser zu versorgen. 1485 ließ der Gemeinderat die Quelle in Gramart beim heutigen Katzenbründlweg östlich der Hungerburg mit einer Leitung in die Stadt verlegen. Mit bis zu vier Meter langen Röhren aus Lärchenholz führte man das saubere Wasser in den Talboden. Bei der Innbrücke zweigte die Leitung links und rechts nach Mariahilf und St. Nikolaus sowie über den Inn in die Stadt und die Neustadt. Bis zur Erbauung dieses kleinen technischen Meisterwerks war Innsbruck wie andere Städte vom Wasser in den Brunnen abhängig. Das Wasser war häufig abgestanden und voll mit Krankheitserregern. Bier und Wein galten nicht umsonst als ungefährlicheres Alltagsgetränk als Wasser. Die Pest konnte man damit zwar nicht dauerhaft fernhalten, Typhus und Cholera waren aber weniger weit verbreitet als in anderen Städten. Nicht nur des Trinkwassers wegen stieg Innsbruck im 15. Jahrhundert von einem kleinen Handelsstützpunkt zur Residenzstadt der Tiroler Landesfürsten auf. Der Brennerpass ist sehr niedrig und erlaubt es, den Alpengürtel, der sich rund um Italiens Nordgrenze schlängelt, verhältnismäßig einfach zu überqueren. In den Zeiten vor die Eisenbahn Waren und Menschen mühelos von A nach B brachte, war die Alpenüberquerung harte Arbeit, der Brenner eine willkommene Erleichterung. Zwischen 1239 und 1303 war Innsbruck die einzige Stadt zwischen „Mellach and Ziller“ in the central Inn Valley, which had the princely right of settlement. Here, goods had to be transferred from one cart to the next within the regulated cartage system, an enormous advantage for Innsbruck's economy. Innsbruck was not quite as rich as Bolzano and had no political significance until the early 15th century, but became one of the most important transport and trade hubs in the Alpine region The former provincial capital of Merano had no chance against the city on the Inn between Brenner, Scharnitz and the Achen Pass in the long term due to its remoteness. Its location in the Alps also favoured tourism, which gained a foothold from the 1860s at the latest. Travellers appreciated the combination of easy accessibility, urban infrastructure and Alpine flair. With the development of the mountainous region by railway, it was easy to travel and spend leisure time in the mountains or at one of the spas without having to forego the comforts of city life. By the time they were tamed by the railway, the Alps had gone from being a source of problems to an economic factor. Gone were the times characterised by difficult agriculture; yesterday's enemy became a saviour.

Neben den Bergen waren die Flüsse maßgeblich an der Entwicklung Innsbrucks beteiligt. Innsbrucks Trinkwasser kam zwar von der Nordkette über eine Wasserleitung in die Stadt, für die sanitäre Versorgung aber waren Inn und Sill zuständig. Das Vieh wurde am Inn zur Tränke geführt, die Wäsche gewaschen und Abfälle aller Art, inklusive Fäkalien von Mensch und Tier, entsorgt. Als die während der Industrialisierung zu wachsen begann, entstand am Sillspitz im Osten der Stadt eine erste Mülldeponie, die später um eine weitere im Westen am heutigen Sieglanger ergänzt wurde. Das Inntal war über 1000 Jahre nach der römischen Besiedlung noch immer ein sumpfiger, von Auwäldern durchzogener Landstrich. Siedlungen wie Wilten, Burgen wie die Festung über Amras und Straßen entstanden etwas vom Fluss entfernt auf Schwemmkegeln oder in Mittelgebirgshöhen. Rund um Innsbruck wurden die Auen als Allmende der Dörfer genutzt. Je nach Wasserhöhe standen Weideland und Brennholz zur Verfügung und der Fluss konnte als Transportweg genutzt werden – oder eben nicht. Flurnamen wie At the pouring in der Höttinger Au erinnern bis heute daran, dass der Inn am heutigen Stadtgebiet bis in die frühe Neuzeit ebenfalls nicht gebändigt, sondern mehr schlecht als recht kultvierte Wildnis war. Überschwemmungen waren immer wieder Folge des unregulierten Flusses. Zwischen 1749 und 1789 forderten mehrere Hochwasser in Innsbruck viele Tote. Auch der wirtschaftliche Schaden war immens. Die Innbrücke spülte Zolleinnahmen in die Stadtkassa und war der Grund, warum die Siedlung zur Stadt werden konnte.

Bis zur Verbesserung des Straßennetzes im 16. Jahrhundert herrschte zwischen Telfs, Innsbruck und Hall reger Schiffsverkehr. Die Flöße, auf denen die Waren transportiert wurden, waren flache Platten mit Dimensionen bis zu 35 x 10 Meter. Mehrere dieser Wasserfahrzeuge bildeten einen Zug, der am Inn bis zur Mündung in die Donau in Passau und weiter nach Osten Waren aller Art verschiffte. Silber, Baumaterialien, Holz, Salz, Weizen, Fleisch – die flussaufwärts auf Treidelwegen genannten Bahnen neben dem Flussbett von Pferden gezogenen Schiffszüge waren der schnellste Weg, um große Mengen an Waren möglichst schnell durchs Inntal transportiert zu bekommen. Auch das Militär nutzte den Inn als Logistikunterstützung. Vom Tiroler Oberland wurde über Jahrhundert hinweg Holz als Trift den Inn flussabwärts geschickt. In Hall fischte ein Holzrechen an der Innbrücke das kostbare Treibgut aus dem Wasser. Innsbruck, vor allem aber die Salz- und Silberbergwerke in Hall und Schwaz benötigten den Werkstoff und Energieträger. Nahe Siedlungen und Städten errichtete man befestigte Archen-Verbauungen, um den Fluss zumindest ein wenig zu zähmen und die Beeinträchtigung von Hochwasser und Dürre einzudämmen. Im 18. Jahrhundert förderten Ökonomisierung und Verwissenschaftlichung, die sich in allen Lebensbereichen bemerkbar machten, auch die Kultivierung der Landschaft. Von diesem Geist der Aufklärung erfasst, wurde auch die Optimierung des Inns als Transportweg und die Erhöhung der Wirtschaftlichkeit des verfügbaren Bodens in Angriff genommen. Die Allmende entlang des Inn wurde mehr und mehr in die Obhut einzelner Grundherren gegeben, die die Urbarmachung dieses Schwemmlandes vorantrieben. Der Theresianische Staatsapparat wollte das habsburgische Riesenreich nicht nur am Landweg mit Straßen, sondern auch über die Hauptflüsse verbinden. Die Verantwortung für Regulierung und Verbauung des Inns ging von den Gemeinden und der Saline Hall auf den Staat über. Innsbrucks erster Chief ark inspector Franz Anton Rangger began mapping the Inn in 1739 in order to make the course of the river easier to plan and faster by straightening and damming it. The project of taming the river was to take more than 100 years. The Napoleonic Wars delayed the construction of the facilities. It was only after the economic hardship of the early 19th century that the state was able to continue the project. Blockstone dams gradually replaced the ark defences. By the time the Inn had been tamed, the railway had replaced shipping as a means of transport. The next major wave of engineering works on the Inn came in the second half of the 20th century. The Olympic Village, the motorway and settlements such as Sieglanger required space that had previously been withheld from the river in order to facilitate the economic miracle of the post-war period.

The smaller river that crosses Innsbruck was almost as important as the Inn. Where the Sill leaves the Sill Gorge today, the Sill Canal was created to supply the city with water. When the Counts of Andechs founded the market at the Inn bridge in 1180, the canal already existed, as the mill of Wilten Abbey in St. Bartlmä was already in operation. From here, the canal continued along the route Karmelitergasse, Adamgasse, Salurnerstraße, Meinhardstraße, Sillgasse, Ing.-Etzel-Straße to Pradler Brücke, where it reconnected with the Sill before flowing into the Inn. Initially intended primarily for fire protection, many businesses soon utilised the water flowing through the town to operate mills for power generation. It was not until the 1970s that the last parts of it disappeared after bombing damaged it during the Second World War.

The final geographical ingredient in the city's success story is the broad valley basin, which favoured Innsbruck's development. As the city grew and the population increased, so did the demand for food. While the farmers in the higher side valleys faced harsh conditions, the Inn Valley offered fertile soil and land for livestock farming and agriculture. Until the High Middle Ages, the Inn Valley was much more heavily forested. In the 13th century, as in many parts of Europe, the area around Innsbruck was subject to major and long-term human intervention in nature for economic purposes. Contrary to what is often portrayed, the Middle Ages were not a primitive time of stagnation. From the 12th century onwards, people no longer relied on prayers and God's grace to escape the effects of regularly occurring crop failures. Innovations such as three-field farming made it possible to feed the agriculturally unproductive urban population, known in modern parlance as the Overhead would call it. The reclamation of the land allowed the town to grow. The towns such as Schwaz, Hall and Innsbruck could not feed themselves, and considerable food imports were required, especially in the early modern period during the mining boom. In addition to meat, it was mainly wine that came to the county of Tyrol from abroad for a long time. Without the local farmers, however, Innsbruck would not have been able to survive. Corn, which Beda Weber considered worthy of mention in Innsbruck's cityscape as early as 1851, is still growing vigorously and even today gives large areas on the outskirts of the city an agricultural flavour.

Tourism: From Alpine summer retreat to Piefke Saga

In the 1990s, an Austrian television series caused a scandal. The Piefke Saga written by the Tyrolean author Felix Mitterer, describes the relationship between the German holidaymaker family Sattmann and their hosts in a fictitious Tyrolean holiday resort in four bizarrely amusing episodes. Despite all the scepticism about tourism in its current, sometimes extreme, excesses, it should not be forgotten that tourism was an important factor in Innsbruck and the surrounding area in the 19th century, driving the region's development in the long term, and not just economically.

The first travellers to Innsbruck were pilgrims and business people. Traders, journeymen on the road, civil servants, soldiers, entourages of aristocratic guests at court, skilled workers from various trades, miners, clerics, pilgrims and scientists were the first tourists to be drawn to the city between Italy and Germany. Travelling was expensive, dangerous and arduous. In addition, a large proportion of the subjects were not allowed to leave their own land without the permission of their landlord or abbot. Those who travelled usually did so on the cobbler's pony. Although Innsbruck's inns and innkeepers were already earning money from travellers in the Middle Ages and early modern times, there was no question of tourism as we understand it today. It began when a few crazy travellers were drawn to the mountain peaks for the first time. In addition to a growing middle class, this also required a new attitude towards the Alps. For a long time, the mountains had been a pure threat to people. It was mainly the British who set out to conquer the world's mountains after the oceans. From the late 18th century, the era of Romanticism, news of the natural beauty of the Alps spread through travelogues. The first foreign-language travel guide to Tyrol, Travells through the Rhaetian Alps by Jean Francois Beaumont was published in 1796.

In addition to the alpine attraction, it was the wild and exotic Natives Tirols, die international für Aufsehen sorgten. Der bärtige Revoluzzer namens Andreas Hofer, der es mit seinem Bauernheer geschafft hatte, Napoleons Armee in die Knie zu zwingen, erzeugte bei den Briten, den notorischen Erzfeinden der Franzosen, ebenso großes Interesse wie bei deutschen Nationalisten nördlich der Alpen, die in ihm einen frühen Protodeutschen sahen. Die Tiroler galten als unbeugsamer Menschenschlag, archetypisch und ungezähmt, ähnlich den Germanen unter Arminius, die das Imperium Romanum herausgefordert hatten. Die Beschreibungen Innsbrucks aus der Feder des Autors Beda Weber (1798 – 1858) und andere Reiseberichte in der boomenden Presselandschaft dieser Zeit trugen dazu bei, ein attraktives Bild Innsbrucks zu prägen.

Nun mussten die wilden Alpen nur noch der Masse an Touristen zugänglich gemacht werden, die zwar gerne den frühen Abenteurern auf ihren Expeditionen nacheifern wollten, deren Risikobereitschaft und Fitness mit den Wünschen nicht schritthalten konnten. Der German Alpine Club eröffnete 1869 eine Sektion Innsbruck, nachdem der 1862 Österreichische Alpenverein was not very successful. Driven by the Greater German idea of many members, the two institutions merged in 1873. Alpine Club is still bourgeois to this day, while its social democratic counterpart is the Naturfreunde. The network of paths grew as a result of its development, as did the number of huts that could accommodate guests. The transit country of Tyrol had countless mule tracks and footpaths that had existed for centuries and served as the basis for alpinism. Small inns, farms and stations along the postal routes served as accommodation. The Tyrolean theologian Franz Senn (1831 - 1884) and the writer Adolf Pichler (1819 - 1900) were instrumental in the surveying of Tyrol and the creation of maps. Contrary to popular belief, the Tyroleans were not born mountaineers, but had to be taught the skills to conquer the mountains. Until then, mountains had been one thing above all: dangerous and arduous in everyday agricultural life. Climbing them had hardly occurred to anyone before. The Alpine clubs also trained mountain guides. From the turn of the century, skiing came into fashion alongside hiking and mountaineering. There were no lifts yet, and to get up the mountains you had to use the skins that are still glued to touring skis today. It was not until the 1920s, following the construction of the cable cars on the Nordkette and Patscherkofel mountains, that a wealthy clientele was able to enjoy the modern luxury of mountain lifts while skiing.

New hotels, cafés, inns, shops and means of transport were needed to meet the needs of guests. Anyone who had running water and a telephone connection at home in London or Paris did not want to make do with an outhouse in the corridor or in front of the house when on holiday. The so-called first and second class inns were suitable for transit traffic, but they were not equipped to receive upscale tourists. Until the 19th century, innkeepers in the city and in the villages around Innsbruck belonged to the upper middle class in terms of income. They were often farmers who ran a pub on the side and sold food. As the example of Andreas Hofer shows, they also had a good reputation and influence within local society. As meeting places for the locals and hubs for postal and goods traffic, they were often well informed about what was happening in the wider world. However, as they were neither members of a guild nor counted among the middle classes, the profession of innkeeper was not one of the most honourable professions. This changed with the professionalisation of the tourism industry. Entrepreneurs such as Robert Nißl, who took over Büchsenhausen Castle in 1865 and converted it into a brewery, invested in the infrastructure. Former aristocratic residences such as Weiherburg Castle became inns and hotels. The revolution in Innsbruck did not take place on the barricades in 1848, but in tourism a few decades later, when resourceful citizens replaced the aristocracy as owners of castles such as Büchsenhausen and Weiherburg.

Opened in 1849, the Österreichischer Hof was long regarded as the top dog of the modern hotel industry, but was officially just a copy of a grand hotel. Only with the Grand Hotel Europa had opened a first-class establishment in Innsbruck in 1869. The heyday of the inns in the old town was over. In 1892, the zeitgeisty Reformhotel Habsburger Hof a second large business. Where the Metropolkino cinema stands today, the Kaiserhof was built as a new building. The Habsburg Court already offered its guests electric light, an absolute sensation. Also on the previously unused area in front of the railway station was the Arlberger Hof settled. What would be seen as a competitive disadvantage today was a selling point at the time. Railway stations were the centres of modern cities. Station squares were not overcrowded transport hubs as they are today, but sophisticated and well-kept places in front of the architecturally sophisticated halls where the trains arrived.

The number of guests increased slowly but steadily. Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, Innsbruck had 200,000 guests. In June 1896, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten:

„Der Fremdenverkehr in Innsbruck bezifferte sich im Monat Mai auf 5647 Personen. Darunter befanden sich (außer 2763 Reisenden aus Oesterreich-Ungarn) 1974 Reichsdeutsche, 282 Engländer, 65 Italiener, 68 Franzosen, 53 Amerikaner, 51 Russen und 388 Personen aus verschiedenen anderen Ländern.“

In addition to the number of travellers who had an impact on life in the small town of Innsbruck, it was also the internationality of the visitors who gradually gave Innsbruck a new look. In addition to the purely touristic infrastructure, the development of general innovations was also accelerated. The wealthy guests could hardly socialise in pubs with cesspits behind their houses. Of course, a sewerage system would have been on the agenda anyway, but the economic factor of tourism made it possible and accelerated the release of funds for the major projects at the turn of the century. This not only changed the appearance of the town, but also people's everyday and working lives. Resourceful entrepreneurs such as Heinrich Menardi managed to expand the value chain to include paid holiday pleasures in addition to board and lodging. In 1880, he opened the Lohnkutscherei und Autovermietung Heinrich Menardi for excursions in the Alpine surroundings. Initially with carriages, and after the First World War with coaches and cars, wealthy tourists were chauffeured as far as Venice. The company still exists today and is now based in the Menardihaus at Wilhelm-Greil-Strasse 17 opposite Landhausplatz, even though over time the transport and trading industry shifted to the more lucrative property sector. Local trade also benefited from the wealthy clientele from abroad. In 1909, there were already three dedicated Tourist equipment shops next to the fashionable department stores that had just opened a few years earlier.

Innsbruck and the surrounding towns were also known for spa holidays, the predecessor of today's wellness, where well-heeled clients recovered from a wide variety of illnesses in an Alpine environment. The Igler Hof, back then Grandhotel Igler Hof and the Sporthotel Igls, still partly exude the chic of that time. Michael Obexer, the founder of the spa town of Igls and owner of the Grand Hotel, was a tourism pioneer. There were two spas in Egerdach near Amras and in Mühlau. The facilities were not as well-known as the hotspots of the time in Bad Ischl, Marienbad or Baden near Vienna, as can be seen on old photos and postcards, but the treatments with brine, steam, gymnastics and even magnetism were in line with the standards of the time, some of which are still popular with spa and wellness holidaymakers today. Bad Egerdach near Innsbruck had been known as a healing spring since the 17th century. The spring was said to cure gout, skin diseases, anaemia and even the nervous disorder known in the 19th century as neurasthenia, the predecessor of burnout. The institution's chapel still exists today opposite the SOS Children's Village. The bathing establishment in Mühlau has existed since 1768 and was converted into an inn and spa in the style of the time in the course of the 19th century. The former bathing establishment is now a residential building worth seeing in Anton-Rauch-Straße. However, the most spectacular tourist project that Innsbruck ever experienced was probably Hoch Innsbruck, today's Hungerburg. Not only the Hungerburg railway and hotels, but even its own lake was created here after the turn of the century to attract guests.

One of the former owners of the land of the Hungerburg and Innsbruck tourism pioneer, Richard von Attlmayr, was significantly involved in the predecessor of today's tourism association. Since 1881, the Innsbruck Beautification Association to satisfy the increasing needs of guests. The association took care of the construction of hiking and walking trails, the installation of benches and the development of impassable areas such as the Mühlauer Klamm or the Sillschlucht gorge. The striking green benches along many paths are a reminder of the still existing association. 1888 years later, the profiteers of tourism in Innsbruck founded the Commission for the promotion of tourismthe predecessor of today's tourism association. By joining forces in advertising and quality assurance at the accommodation establishments, the individual businesses hoped to further boost tourism.

„Alljährlich mehrt sich die Zahl der überseeischen Pilger, die unser Land und dessen gletscherbekrönte Berge zum Verdrusse unserer freundnachbarlichen Schweizer besuchen und manch klingenden Dollar zurücklassen. Die Engländer fangen an Tirol ebenso interessant zu finden wie die Schweiz, die Zahl der Franzosen und Niederländer, die den Sommer bei uns zubringen, mehrt sich von Jahr zu Jahr.“

Postkarten waren die ersten massentauglichen Influencer der Tourismusgeschichte. Viele Betriebe ließen ihre eigenen Postkarten drucken. Verlage produzierten unzählige Sujets der beliebtesten Sehenswürdigkeiten der Stadt. Es ist interessant zu sehen, was damals als sehenswert galt und auf den Karten abgebildet wurde. Anders als heute waren es vor allem die zeitgenössisch modernen Errungenschaften der Stadt: der Leopoldbrunnen, das Stadtcafé beim Theater, die Kettenbrücke, die Zahnradbahn auf die Hungerburg oder die 1845 eröffnete Stefansbrücke an der Brennerstraße, die als Steinbogen aus Quadern die Sill überquerte, waren die Attraktionen. Auch Andreas Hofer war ein gut funktionierendes Testimonial auf den Postkarten: Der Gasthof Schupfen in dem Andreas Hofer sein Hauptquartier hatte und der Berg Isel mit dem großen Andreas-Hofer-Denkmal waren gerne abgebildete Motive.

1914 gab es in Innsbruck 17 Hotels, die Gäste anlockten. Dazu kamen die Sommer- und Winterfrischler in Igls und dem Stubaital. Der Erste Weltkrieg ließ die erste touristische Welle mit einem Streich versanden. Gerade als sich der Fremdenverkehr Ende der 1920er Jahre langsam wieder erholt hatte, kamen mit der Wirtschaftskrise und Hitlers 1000 Mark blockThe next setback came in 1933, when he tried to put pressure on the Austrian government to end the ban on the NSDAP.

It required the Economic miracle in the 1950s and 1960s to revitalise tourism in Innsbruck after the destruction. Between 1955 and 1972, the number of overnight stays in Tyrol increased fivefold. After the arduous war years and the reconstruction of the European economy, Tyrol and Innsbruck were able to slowly but steadily establish tourism as a stable source of income, even away from the official hotels and guesthouses. Many Innsbruck families moved together in their already cramped flats to supplement their household budgets by renting out beds to guests from abroad. Tourism not only brought in foreign currency, but also enabled the locals to create a new image of themselves both internally and externally. At the same time, the economic upturn made it possible for more and more Innsbruck residents to go on holiday abroad. The beaches of Italy were particularly popular. The wartime enemies of previous decades became guests and hosts.

A republic is born

Few eras are more difficult to grasp than the interwar period. The Roaring TwentiesJazz and automobiles come to mind, as do inflation and the economic crisis. In big cities like Berlin, young ladies behaved as Flappers mit Bubikopf, Zigarette und kurzen Röcken zu den neuen Klängen lasziv, Innsbrucks Bevölkerung gehörte als Teil der jungen Republik Österreich zum größten Teil zur Fraktion Armut, Wirtschaftskrise und politischer Polarisierung. Schon die Ausrufung der Republik am Parlament in Wien vor über 100.000 mehr oder minder begeisterten, vor allem aber verunsicherten Menschen verlief mit Tumulten, Schießereien, zwei Toten und 40 Verletzten alles andere als reibungsfrei. Wie es nach dem Ende der Monarchie und dem Wegfall eines großen Teils des Staatsterritoriums weitergehen sollte, wusste niemand. Das neue Österreich erschien zu klein und nicht lebensfähig. Der Beamtenstaat des k.u.k. Reiches setzte sich nahtlos unter neuer Fahne und Namen durch. Die Bundesländer als Nachfolger der alten Kronländer erhielten in der Verfassung im Rahmen des Föderalismus viel Spielraum in Gesetzgebung und Verwaltung. Die Begeisterung für den neuen Staat hielt sich aber in der Bevölkerung in Grenzen. Nicht nur, dass die Versorgungslage nach dem Wegfall des allergrößten Teils des ehemaligen Riesenreiches der Habsburger miserabel war, die Menschen misstrauten dem Grundgedanken der Republik. Die Monarchie war nicht perfekt gewesen, mit dem Gedanken von Demokratie konnten aber nur die allerwenigsten etwas anfangen. Anstatt Untertan des Kaisers war man nun zwar Bürger, allerdings nur Bürger eines Zwergstaates mit überdimensionierter und in den Bundesländern wenig geliebter Hauptstadt anstatt eines großen Reiches. In den ehemaligen Kronländern, die zum großen Teil christlich-sozial regiert wurden, sprach man gerne vom Viennese water headwho was fed by the yields of the industrious rural population.

Other federal states also toyed with the idea of seceding from the Republic after the plan to join Germany, which was supported by all parties, was prohibited by the victorious powers of the First World War. The Tyrolean plans, however, were particularly spectacular. From a neutral Alpine state with other federal states, a free state consisting of Tyrol and Bavaria or from Kufstein to Salurn, an annexation to Switzerland and even a Catholic church state under papal leadership, there were many ideas. The most obvious solution was particularly popular. In Tyrol, feeling German was nothing new. So why not align oneself politically with the big brother in the north? This desire was particularly pronounced among urban elites and students. The annexation to Germany was approved by 98% in a vote in Tyrol, but never materialised.

Instead of becoming part of Germany, they were subject to the unloved Wallschen. Italian troops occupied Innsbruck for almost two years after the end of the war. At the peace negotiations in Paris, the Brenner Pass was declared the new border. The historic Tyrol was divided in two. The military was stationed at the Brenner Pass to secure a border that had never existed before and was perceived as unnatural and unjust. In 1924, the Innsbruck municipal council decided to name squares and streets around the main railway station after South Tyrolean towns. Bozner Platz, Brixnerstrasse and Salurnerstrasse still bear their names today. Many people on both sides of the Brenner felt betrayed. Although the war was far from won, they did not see themselves as losers to Italy. Hatred of Italians reached its peak in the interwar period, even if the occupying troops were emphatically lenient. A passage from the short story collection "The front above the peaks" by the National Socialist author Karl Springenschmid from the 1930s reflects the general mood:

"The young girl says, 'Becoming Italian would be the worst thing.

Old Tappeiner just nods and grumbles: "I know it myself and we all know it: becoming a whale would be the worst thing."

Trouble also loomed in domestic politics. The revolution in Russia and the ensuing civil war with millions of deaths, expropriation and a complete reversal of the system cast its long shadow all the way to Austria. The prospect of Soviet conditions machte den Menschen Angst. Österreich war tief gespalten. Hauptstadt und Bundesländer, Stadt und Land, Bürger, Arbeiter und Bauern – im Vakuum der ersten Nachkriegsjahre wollte jede Gruppe die Zukunft nach ihren Vorstellungen gestalten. Die Kulturkämpfe der späten Monarchie zwischen Konservativen, Liberalen und Sozialisten setzte sich nahtlos fort. Die Kluft bestand nicht nur auf politischer Ebene. Moral, Familie, Freizeitgestaltung, Erziehung, Glaube, Rechtsverständnis – jeder Lebensbereich war betroffen. Wer sollte regieren? Wie sollten Vermögen, Rechte und Pflichten verteilt werden. Ein kommunistischer Umsturz war besonders in Tirol keine reale Gefahr, ließ sich aber medial gut als Bedrohung instrumentalisieren, um die Sozialdemokratie in Verruf zu bringen. 1919 hatte sich in Innsbruck zwar ein Workers', farmers' and soldiers' council nach sowjetischem Vorbild ausgerufen, sein Einfluss blieb aber gering und wurde von keiner Partei unterstützt. Ab 1920 bildeten sich offiziell sogenannten Soldatenräte, die aber christlich-sozial dominiert waren. Das bäuerliche und bürgerliche Lager rechts der Mitte militarisierte sich mit der Tiroler Heimatwehr professioneller und konnte sich über stärkeren Zulauf freuen als linke Gruppen, auch dank kirchlicher Unterstützung. Die Sozialdemokratie wurde von den Kirchkanzeln herab und in konservativen Medien als Jewish Party and homeless traitors to their country. They were all too readily blamed for the lost war and its consequences. The Tiroler Anzeiger summarised the people's fears in a nutshell: "Woe to the Christian people if the Jews=Socialists win the elections!".

With the new municipal council regulations of 1919, which provided for universal suffrage for all adults, the Innsbruck municipal council comprised 40 members. Of the 24,644 citizens called to the ballot box, an incredible 24,060 exercised their right to vote. Three women were already represented in the first municipal council with free elections. While in the rural districts the Tyrolean People's Party as a merger of Farmers' Union, People's Association und Catholic Labour Despite the strong headwinds in Innsbruck, the Social Democrats under the leadership of Martin Rapoldi were always able to win between 30 and 50% of the vote in the first elections in 1919. The fact that the Social Democrats did not succeed in winning the mayor's seat was due to the majorities in the municipal council formed by alliances with other parties. Liberals and Tyrolean People's Party was at least as hostile to social democracy as he was to the federal capital Vienna and the Italian occupiers.

But high politics was only the framework of the actual misery. The as Spanish flu This epidemic, which has gone down in history, also took its toll in Innsbruck in the years following the war. Exact figures were not recorded, but the number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 27 - 50 million. In Innsbruck, at the height of the Spanish flu epidemic, it is estimated that around 100 people fell victim to the disease every day. Many Innsbruck residents had not returned home from the battlefields and were missing as fathers, husbands and labourers. Many of those who had made it back were wounded and scarred by the horrors of war. As late as February 1920, the „Tyrolean Committee of the Siberians" im Gasthof Breinößl "...in favour of the fund for the repatriation of our prisoners of war..." organised a charity evening. Long after the war, the province of Tyrol still needed help from abroad to feed the population. Under the heading "Significant expansion of the American children's aid programme in Tyrol" was published on 9 April 1921 in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten to read: "Taking into account the needs of the province of Tyrol, the American representatives for Austria have most generously increased the daily number of meals to 18,000 portions.“

Then there was unemployment. Civil servants and public sector employees in particular lost their jobs after the League of Nations linked its loan to severe austerity measures. Salaries in the public sector were cut. There were repeated strikes. Tourism as an economic factor was non-existent due to the problems in the neighbouring countries, which were also shaken by the war. The construction industry, which had been booming before the war, collapsed completely. Innsbruck's largest company Huter & Söhne hatte 1913 über 700 Mitarbeiter, am Höhepunkt der Wirtschaftskrise 1933 waren es nur noch 18. Der Mittelstand brach zu einem guten Teil zusammen. Der durchschnittliche Innsbrucker war mittellos und mangelernährt. Oft konnten nicht mehr als 800 Kalorien pro Tag zusammengekratzt werden. Die Kriminalitätsrate war in diesem Klima der Armut höher als je zuvor. Viele Menschen verloren ihre Bleibe. 1922 waren in Innsbruck 3000 Familien auf Wohnungssuche trotz eines städtischen Notwohnungsprogrammes, das bereits mehrere Jahre in Kraft war. In alle verfügbaren Objekte wurden Wohnungen gebaut. Am 11. Februar 1921 fand sich in einer langen Liste in den Innsbrucker Nachrichten on the individual projects that were run, including this item:

„The municipal hospital abandoned the epidemic barracks in Pradl and made them available to the municipality for the construction of emergency flats. The necessary loan of 295 K (note: crowns) was approved for the construction of 7 emergency flats.“

Very little happened in the first few years. Then politics awoke from its lethargy. The crown, a relic from the monarchy, was replaced by the schilling as Austria's official currency on 1 January 1925. The old currency had lost more than 95% of its value against the dollar between 1918 and 1922, or the pre-war exchange rate. Innsbruck, like many other Austrian municipalities, began to print its own money. The amount of money in circulation rose from 12 billion crowns to over 3 trillion crowns between 1920 and 1922. The result was an epochal inflation.

With the currency reorganisation following the League of Nations loan under Chancellor Ignaz Seipel, not only banks and citizens picked themselves up, but public building contracts also increased again. Innsbruck modernised itself. There was what economists call a false boom. This short-lived economic recovery was a Bubble, However, the city of Innsbruck was awarded major projects such as the Tivoli, the municipal indoor swimming pool, the high road to the Hungerburg, the mountain railways to the Isel and the Nordkette, new schools and apartment blocks. The town bought Lake Achensee and, as the main shareholder of TIWAG, built the power station in Jenbach. The first airport was built in Reichenau in 1925, which also involved Innsbruck in air traffic 65 years after the opening of the railway line. In 1930, the university bridge connected the hospital in Wilten and the Höttinger Au. The Pembaur Bridge and the Prince Eugene Bridge were built on the River Sill. The signature of the new, large mass parties in the design of these projects cannot be overlooked.

The first republic was a difficult birth from the remnants of the former monarchy and it was not to last long. Despite the post-war problems, however, a lot of positive things also happened in the First Republic. Subjects became citizens. What began in the time of Maria Theresa was now continued under new auspices. The change from subject to citizen was characterised not only by a new right to vote, but above all by the increased care of the state. State regulations, schools, kindergartens, labour offices, hospitals and municipal housing estates replaced the benevolence of the landlord, sovereigns, wealthy citizens, the monarchy and the church.

To this day, much of the Austrian state and Innsbruck's cityscape and infrastructure are based on what emerged after the collapse of the monarchy. In Innsbruck, there are no conscious memorials to the emergence of the First Republic in Austria. The listed residential complexes such as the Slaughterhouse blockthe Pembaurblock or the Mandelsbergerblock oder die Pembaur School are contemporary witnesses turned to stone. Every year since 1925, World Savings Day has commemorated the introduction of the schilling. Children and adults should be educated to handle money responsibly.

Sporty Innsbruck

Wer den Beweis benötigt, dass die Innsbrucker stets ein aktives Völkchen waren, könnte das Bild „Winterlandschaft“ des niederländischen Malers Pieter Bruegel (circa 1525 – 1569) aus dem 16. Jahrhundert bemühen. Auf seiner Rückreise von Italien gen Norden hielt der Meister wohl auch in Innsbruck und beobachtete dabei die Bevölkerung beim Eislaufen auf dem zugefrorenen Amraser See. Beda Weber beschrieb in seinem Handbuch für Reisende in Tirol 1851 the leisure habits of the people of Innsbruck, including ice skating on Lake Amras. "The lake not far away (note: Amras), a pool in the mossy area, is used by ice skaters in winter." To this day, sporty clothing in every situation is the most normal thing in the world for Innsbruckers. While in other cities people turn up their noses at functional clothing or hiking and sports shoes in restaurants or offices, at the foot of the Nordkette you don't stand out.

It wasn't always like that. The path from ice-skating peasant to active citizen was a long one. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, leisure and free time for sports such as hunting or riding was primarily a privilege of the nobility. It was not until the changed living conditions of the 19th century that a large proportion of the population, especially in the cities, had something like leisure time for the first time. More and more people no longer worked in agriculture, but as labourers and employees in offices, workshops and factories according to regulated schedules.

The pioneer was the early industrialised England, where workers and employees slowly began to free themselves from the turbo capitalism of early industrialisation. 16-hour days were not only detrimental to workers' health, entrepreneurs also realised that overworking was unprofitable. Healthy and happy workers were better for productivity. Efforts to introduce an 8-hour day had been underway since the 1860s. In 1873, the Austrian book printers pushed through a working day of ten hours. In 1918, Austria switched to a 48-hour week. From 1930, 40 hours per week became the standard working time in industrial companies. People of all classes, no longer just the aristocracy, now had time and energy for hobbies, club life and sporting activities.

In many cases, it was also English tourists who brought sporting trends, disciplines and equipment with them. The financial outlay for the required equipment determined whether the discipline remained the preserve of the middle classes or whether labourers could also afford the pleasure. For example, luge was already widespread around the turn of the century, while bobsleigh and skeleton remained elitist sports. Sport was not just a leisure activity, but a demarcation between the individual social classes. The working classes, bourgeoisie and aristocracy also nurtured their identity through the sports they practised. Aristocrats rode and hunted with the dignity of old, the middle classes showed their individuality, wealth and independence through expensive sports equipment such as modern bicycles, and the working classes chased balls or wrestled in teams of eleven. The separation may no longer be conscious, but you can still see people identifying with „their“ sport today.

In the middle of the 19th century, sportsmen and women joined singers, museum and theatre enthusiasts, scientists and literature fans. The beginning of organised club sport in Innsbruck was marked by the ITV, the Innsbrucker Turnvereinwhich was founded in 1849. Gymnastics was the epitome of sport in German-speaking countries. The idea of competition was not in the foreground. Most clubs had a political background. There were Christian, socialist and Greater German sports clubs. They served as a preliminary organisation for political parties and bodies. More or less all clubs had Aryan clauses in their statutes. Jews therefore founded their own sports clubs. The national movement emerged from the German gymnastics clubs, similar to the student fraternities. The members were supposed to train themselves physically in order to fulfil the national body to serve in the best possible way in the event of war. Sedentary occupations, especially academic ones, became more common, and gymnastics served as a means of compensation. If you see the gymnasts performing their exercises and demonstrations in old pictures, the strictly military character of these events is striking. The Greater German agitator Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778 - 1852), commonly known as Gymnastics father Jahnwas not only the nation's gymnast, but also the spiritual father of the Lützow Free Corps which went into action against Napoleon as a kind of all-German volunteer army. One of the most famous bon mots attributed to this passionate anti-Semite is "Hatred of everything foreign is a German's duty". In Saggen, Jahnstraße and a small park with a monument commemorate Friedrich Ludwig Jahn.

Swimming pools were among the first sports facilities. The first bathing establishment welcomed swimmers from 1833 in the Höttinger in the outdoor pool on the Gießen. Further baths at Büchsenhausen Castle or the separate women's and men's baths next to today's Sillpark area soon followed. The outdoor swimming pool was in a particularly beautiful location Beautiful rest above Ambras Castle, which opened in 1929 shortly after the indoor swimming pool in Pradl was built. The population had grown just as much as the desire for swimming as a leisure activity. In 1961, the sports programme at Tivoli was expanded to include the Freischwimmbad Tivoli extended.

1883 gründeten die Radfahrer den Verein Bicycle Club. The first bicycle races in France and Great Britain took place from 1869. The English city of Coventry was also a pioneer in the production of the elegant steel steeds, which cost a fortune. In the same year, the Innsbruck press had already reported on the modern means of personal transport when "some gentlemen ventured onto the road with several velocipedes ordered by the Peterlongo company". In 1876, cycling was briefly banned in Innsbruck as accidents had repeatedly occurred. Cycling was also quickly recognised by the state as a form of exercise that could be used for military purposes. A Reich war ministerial decree on this can be found in the press:

„Es ist beabsichtigt, wie in den Vorjahren, auch heuer bei den Uebungen mit vereinigten Waffen Radfahrer zu verwenden… Die Commanden der Infanterie- und Tiroler Jägerregimenter sowie der Feldjäger-Bataillone haben jene Personen, welche als Radfahrer in Evidenz stehen und heuer zur Waffenübung verpflichtet sind, zum Einrücken mit ihrem Fahrrade aufzufordern.“

The scene continued to develop before the turn of the century under the direction of Anton Schlumpeter from Munich. Schlumpeter covered the entire value chain with a riding school, a bicycle shop and workshop and finally the Veldidena bicycle brand produced in his Wilten factory. The Velocipedists siedelten sich 1896 im Rahmen der „Internationalen Ausstellung für körperliche Erziehung, Gesundheitspflege und Sport" in Saggen near the viaduct arches with a cycling track and grandstand. The Innsbrucker Nachrichten newspaper reported enthusiastically on this innovation, as cycling was the most popular sporting discipline in Europe until the first car races:

„Die Innsbrucker Rennbahn, welche in Verbindung mit der internationalen Ausstellung noch im Laufe der nächsten Wochen eröffnet wird, erhält einen Umfang von 400 Metern bei einer Breite von 6 Metern… Die Velociped-Rennbahn, um deren Errichtung sich der Präsident des Tiroler Radfahrer-Verbandes Herr Staatsbahn-Oberingenieur R. v. Weinong, das Hauptverdienst erworben hat, wird eine der hervorragendsten und besteingerichteten Radfahrbahnen des Continents sein. Am. 29. d. M. (Anm.: Juni 1896) wird auf der Innsbrucker Rennbahn zum erstenmale ein großes internationales Radwettfahren abgehalten, welchem dann in der Zukunft alljährlich regelmäßig Velociped-Preisrennen folgen sollen, was der Förderung des Radfahr-Sports wie auch des Fremdenverkehrs in Innsbruck sicher in bedeutendem Maße nützlich sein wird.“

The cement railway was used for daily training in the warm season. The smoke-filled air as the locomotives passed by was probably not good for the lungs. After initial enthusiasm, Schlumpeter had to step in to save the railway. The enterprising entrepreneur realised that the cyclists were not providing enough activity and, on his own initiative, began to build a kind of predecessor to today's Olympiaworld at the Tivoli with several facilities for sport. In addition to cycling races, boxers could compete in the ring. He also had tennis courts built in Saggen. Despite all his efforts, the facility was demolished again in 1901.

Football was able to establish itself in Innsbruck more sustainably than cycling. The footballers had left the umbrella organisation ITV due to the Aryan law, which forbade matches with teams with Jewish players, and founded several clubs of their own. Verein Fußball Innsbruckwhich would later become the SVI. At this time, there were already national football matches, for example a 1:1 draw between the ITV team and Bayern Munich. The matches were played on a football pitch in front of the Sieberer orphanage. In Wilten, now part of Innsbruck, in 1910 the SK Wilten. The Besele football pitch, which still exists today next to the Westfriedhof cemetery, was equipped with stands to cope with the masses of spectators. 1913 saw the founding of Wacker Innsbruck the most successful Tyrolean football club to date, winning the Austrian championship ten times under different names and also celebrating international success.

In addition to the various summer sports, winter sports also became increasingly popular. Tobogganing was already a popular leisure activity on the hills around Innsbruck in the middle of the 19th century. The first ice rink opened in 1870 as a winter alternative to swimming on the grounds of the open-air swimming pool in the Höttinger Au. Unlike water sports, ice skating was a pleasure that could be enjoyed by men and women together. Instead of meeting up for a Sunday stroll, young couples could meet at the ice rink without their parents present. The ice skating club was founded in 1884 and used the exhibition grounds as an ice rink. With the ice rink in front of the k.u.k. shooting range in Mariahilf, the Lansersee, the Amraser See, the Höttinger Au swimming facility and the Sillkanal in Kohlstatt provided the people of Innsbruck with many opportunities for ice skating. The first ice hockey club, the IEV, was founded as early as 1908.

Skiing, initially a Nordic pastime in the valley, soon spread as a downhill discipline. The Innsbruck Academic Alpine Club was founded in 1893 and two years later organised the first ski race on Tyrolean soil from Sistrans to Ambras Castle. Founded in 1867, the Sports shop Witting in Maria-Theresien-Straße proved its business acumen and was still selling equipment for the well-heeled skiing public before 1900. After St. Anton and Kitzbühel, the first ski centre was founded in 1906. Innsbruck Ski Club. The equipment was simple and for a long time only allowed skiing on relatively flat slopes with a mixture of alpine and Nordic style similar to cross-country skiing. Nevertheless, people dared to whizz down the slopes in Mutters or on the Ferrariwiese. In 1928, two cable cars were installed on the Nordkette and the Patscherkofel, which made skiing significantly more attractive. Skiing achieved its breakthrough as a national sport with the World Ski Championships in Innsbruck in February 1933. On an unmarked course, 10 kilometres and 1500 metres of altitude had to be covered between the Glungezer and Tulfes. The two local heroes Gustav Lantschner and Inge Wersin-Lantschner won several medals in the races, fuelling the hype surrounding alpine winter sports in Innsbruck.

Innsbruck identifiziert sich bis heute sehr stark mit dem Sport. Mit der Fußball-EM 2008, der Radsport-WM 2018 und der Kletter-WM 2018 konnte man an die glorreichen 1930er Jahre mit zwei Skiweltmeisterschaften und die beiden Olympiaden von 1964 und 1976 auch im Spitzensportbereich wieder an die Goldenen Zeiten anknüpfen. Trotzdem ist es weniger der Spitzen- als vielmehr der Breitensport, der dazu beiträgt, aus Innsbruck die selbsternannte Sporthauptstadt Österreichs zu machen. Es gibt kaum einen Innsbrucker, der nicht zumindest den Alpinski anschnallt. Mountainbiken auf den zahlreichen Almen rund um Innsbruck, Skibergsteigen, Sportklettern und Wandern sind überdurchschnittlich populär in der Bevölkerung und fest im Alltag verankert.

Wilhelm Greil: DER Bürgermeister Innsbrucks

One of the most important figures in the town's history was Wilhelm Greil (1850 - 1923). From 1896 to 1923, the entrepreneur held the office of mayor, having previously helped to shape the city's fortunes as deputy mayor. It was a time of growth, the incorporation of entire neighbourhoods, technical innovations and new media. The four decades between the economic crisis of 1873 and the First World War were characterised by unprecedented economic growth and rapid modernisation. Private investment in infrastructure such as railways, energy and electricity was desired by the state and favoured by tax breaks in order to lead the countries and cities of the ailing Danube monarchy into the modern age. The city's economy boomed. Businesses sprang up in the new districts of Pradl and Wilten, attracting workers. Tourism also brought fresh capital into the city. At the same time, however, the concentration of people in a confined space under sometimes precarious hygiene conditions also brought problems. The outskirts of the city and the neighbouring villages in particular were regularly plagued by typhus.

Innsbruck city politics, in which Greil was active, was characterised by the struggle between liberal and conservative forces. Greil belonged to the "Deutschen Volkspartei", a liberal and national-Great German party. What appears to be a contradiction today, liberal and national, was a politically common and well-functioning pair of ideas in the 19th century. The Pan-Germanism was not a political peculiarity of a radical right-wing minority, but rather a centrist trend, particularly in German-speaking cities in the Reich, which was significant in various forms across almost all parties until after the Second World War. Innsbruckers who were self-respecting did not describe themselves as Austrians, but as Germans. Those who were members of the liberal Innsbrucker Nachrichten of the period around the turn of the century, you will find countless articles in which the common ground between the German Empire and the German-speaking countries was made the topic of the day, while distancing themselves from other ethnic groups within the multinational Habsburg Empire. Greil was a skilful politician who operated within the predetermined power structures of his time. He knew how to skilfully manoeuvre around the traditional powers, the monarchy and the clergy and to come to terms with them.

Taxes, social policy, education, housing and the design of public spaces were discussed with passion and fervour. Due to an electoral system based on voting rights via property classes, only around 10% of the entire population of Innsbruck were able to go to the ballot box. Women were excluded as a matter of principle. Relative suffrage applied within the three electoral bodies, which meant as much as: The winner takes it all. Greil wohne passenderweise ähnlich wie ein Renaissancefürst. Er entstammte der großbürgerlichen Upper Class. Sein Vater konnte es sich leisten, im Palais Lodron in der Maria-Theresienstraße die Homebase der Familie zu gründen. Massenparteien wie die Sozialdemokratie konnten sich bis zur Wahlrechtsreform der Ersten Republik nicht durchsetzen. Konservative hatten es in Innsbruck auf Grund der Bevölkerungszusammensetzung, besonders bis zur Eingemeindung von Wilten und Pradl, ebenfalls schwer. Bürgermeister Greil konnte auf 100% Rückhalt im Gemeinderat bauen, was die Entscheidungsfindung und Lenkung natürlich erheblich vereinfachte. Bei aller Effizienz, die Innsbrucker Bürgermeister bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung an den Tag legten, sollte man nicht vergessen, dass das nur möglich war, weil sie als Teil einer Elite aus Unternehmern, Handelstreibenden und Freiberuflern ohne nennenswerte Opposition und Rücksichtnahme auf andere Bevölkerungsgruppen wie Arbeitern, Handwerkern und Angestellten in einer Art gewählten Diktatur durchregierten. Das Reichsgemeindegesetz von 1862 verlieh Städten wie Innsbruck und damit den Bürgermeistern größere Befugnisse. Es verwundert kaum, dass die Amtskette, die Greil zu seinem 60. Geburtstag von seinen Kollegen im Gemeinderat verliehen bekam, den Ordensketten des alten Adels erstaunlich ähnelte.

Under Greil's aegis and the general economic upturn, fuelled by private investment, Innsbruck expanded at a rapid pace. In true merchant style, the municipal council purchased land with foresight in order to enable the city to innovate. The politician Greil was able to rely on the civil servants and town planners Eduard Klingler, Jakob Albert and Theodor Prachensky for the major building projects of the time. Infrastructure projects such as the new town hall in Maria-Theresienstraße in 1897, the opening of the Mittelgebirgsbahn railway, the Hungerburgbahn and the Karwendelbahn wurden während seiner Regierungszeit umgesetzt. Weitere gut sichtbare Meilensteine waren die Erneuerung des Marktplatzes und der Bau der Markthalle. Neben den prestigeträchtigen Großprojekten entstanden in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts aber viele unauffällige Revolutionen. Vieles, was in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts vorangetrieben wurde, gehört heute zum Alltag. Für die Menschen dieser Zeit waren diese Dinge aber eine echte Sensation und lebensverändernd. Bereits Greils Vorgänger Bürgermeister Heinrich Falk (1840 – 1917) hatte erheblich zur Modernisierung der Stadt und zur Besiedelung des Saggen beigetragen. Seit 1859 war die Beleuchtung der Stadt mit Gasrohrleitungen stetig vorangeschritten. Mit dem Wachstum der Stadt und der Modernisierung wurden die Senkgruben, die in Hinterhöfen der Häuser als Abort dienten und nach Entleerung an umliegende Landwirte als Dünger verkauft wurden, zu einer Unzumutbarkeit für immer mehr Menschen. 1880 wurde das RaggingThe city was responsible for the emptying of the lavatories. Two pneumatic machines were to make the process at least a little more hygienic. Between 1887 and 1891, Innsbruck was equipped with a modern high-pressure water pipeline, which could also be used to supply fresh water to flats on higher floors. For those who could afford it, this was the first opportunity to install a flush toilet in their own home.

Greil continued this campaign of modernisation. After decades of discussions, the construction of a modern alluvial sewerage system began in 1903. Starting in the city centre, more and more districts were connected to this now commonplace luxury. By 1908, only the Koatlackler Mariahilf und St. Nikolaus nicht an das Kanalsystem angeschlossen. Auch der neue Schlachthof im Saggen erhöhte Hygiene und Sauberkeit in der Stadt. Schlecht kontrollierte Hofschlachtungen gehörten mit wenigen Ausnahmen der Vergangenheit an. Das Vieh kam im Zug am Sillspitz an und wurde in der modernen Anlage fachgerecht geschlachtet. Greil überführte auch das Gaswerk in Pradl und das Elektrizitätswerk in Mühlau in städtischen Besitz. Die Straßenbeleuchtung wurde im 20. Jahrhundert von den Gaslaternen auf elektrisches Licht umgestellt. 1888 übersiedelte das Krankenhaus von der Maria-Theresienstraße an seinen heutigen Standort. Bürgermeister und Gemeinderat konnten sich bei dieser Innsbrucker Renaissance neben der wachsenden Wirtschaftskraft in der Vorkriegszeit auch auf Mäzen aus dem Bürgertum stützen. Waren technische Neuerungen und Infrastruktur Sache der Liberalen, verblieb die Fürsorge der Ärmsten weiterhin bei klerikal gesinnten Kräften, wenn auch nicht mehr bei der Kirche selbst. Freiherr Johann von Sieberer stiftete das Greisenasyl und das Waisenhaus im Saggen. Leonhard Lang stiftete das Gebäude in der Maria-Theresienstraße, in der sich bis heute das Rathaus befindet gegen das Versprechen der Stadt ein Lehrlingsheim zu bauen.

Im Gegensatz zur boomenden Vorkriegsära war die Zeit nach 1914 vom Krisenmanagement geprägt. In seinen letzten Amtsjahren begleitete Greil Innsbruck am Übergang von der Habsburgermonarchie zur Republik durch Jahre, die vor allem durch Hunger, Elend, Mittelknappheit und Unsicherheit geprägt waren. Er war 68 Jahre alt, als italienische Truppen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg die Stadt besetzten und Tirol am Brenner geteilt wurde. Das Ende der Monarchie und des Zensuswahlrechts bedeuteten auch den Niedergang der Liberalen in Innsbruck, auch wenn Greil das in seiner aktiven Karriere nur teilweise miterlebte. 1919 konnten die Sozialdemokraten in Innsbruck zwar zum ersten Mal den Wahlsieg davontragen, dank der Mehrheiten im Gemeinderat blieb Greil aber Bürgermeister. 1928 verstarb er als Ehrenbürger der Stadt Innsbruck im Alter von 78 Jahren. Die Wilhelm-Greil-Straße war noch zu seinen Lebzeiten nach ihm benannt worden.