Weinhaus Happ

Herzog-Friedrich-Straße 14

Worth knowing

The Weinhaus Happ was already supplying locals and visitors with the eponymous grape juice in the 15th century. In 1427, Tyrolean Prince Frederick IV granted Innsbruck's innkeepers permission to serve wine. From its earliest days, Innsbruck was an important base for the wine trade to the north. The city is located on the imaginary border between the beer and wine regions. In cooler northern Europe, people mainly drank beer, while in the Mediterranean countries they drank the wine that grew there. Innsbruck, as a trading city between Italy and Germany, was a centre of trade from north and south of this border. Wine-beer line influenced. For a long time, wine was not an intoxicating drink, but a foodstuff. While water from wells could not be trusted in the Middle Ages, especially in large cities, wine was tolerable. Wine was lighter than it is today, so people in the Middle Ages and early modern times were not constantly drunk.

In 1783, the building first appeared as a pub under the brewer Martin Juffing. After numerous changes of ownership, Franz Happ took over the pub in 1874. Like many other buildings in the old town, the Weinhaus Happ were in a miserable state at the time. Unlike today, old buildings steeped in history did not correspond to the public's taste, but were considered outdated. After the façade collapsed, it had to be completely renovated.

Maria Schwarz took over the Happ in 1921. As in many other pubs, theatre plays were performed in the inn right next to the Golden Roof. Little by little, it became an Innsbruck institution.

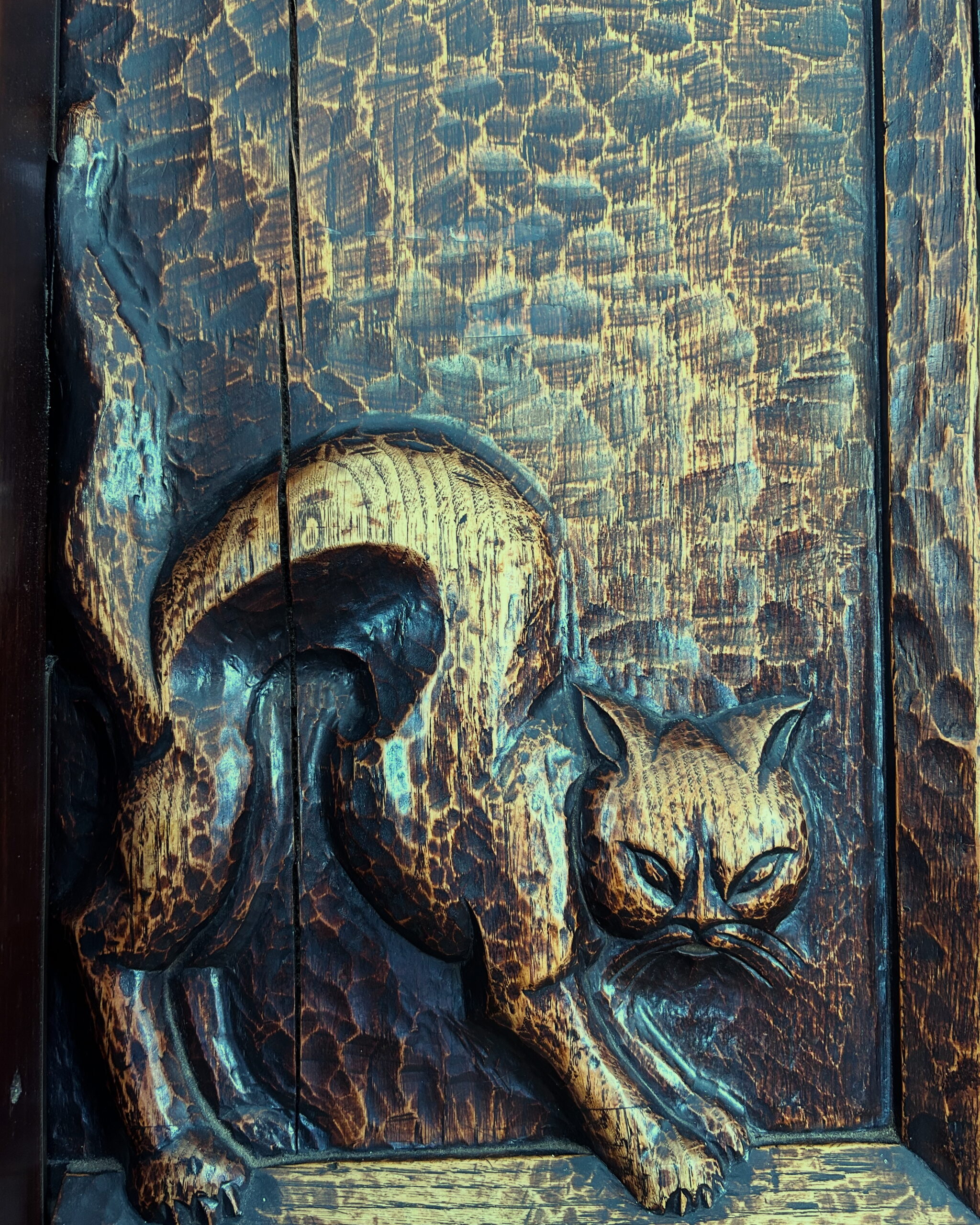

In 1927, the pub's parlour was redesigned according to the plans of the then unknown architect Franz Baumann (1892 - 1974). The challenge was to renovate and modernise the building without disturbing the townscape. For a year, the Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association, together with the district administration, had the final say on building projects in sensitive locations. Urban planning should not be created on the drawing board, but should take historical town centres into consideration. Baumann designed the façade in the cubic style of the Neuen Sachlichkeitthe ornately carved entrance door, the sweeping house sign, the staircase, the guest rooms and the furniture. Instead of a fully panelled parlour, he used wood more sparingly. By using new materials, he succeeded in bringing the Tyrolean style and the cosiness of the traditional parlour into the modern age without betraying it. The centre-axis bay window was a popular stylistic element of the time, which Prachensky also used repeatedly in the design of the building above the passageway to the Sparkasse in Maria-Theresien-Straße and in his large-scale projects. The parlour inside was affectionately renamed the Baumannstube after Baumann's rise to become one of the leading architects of his time.

The façade paintings of the Weinhaus Happ date from the interwar period. The South Tyrolean peasant motifs, including an image of St Urban, the patron saint of winegrowers, were created by Erich Torggler in 1937. The different climatic conditions north and south of the main Alpine ridge resulted in different types of cultivation. While wine in the south was primarily an export commodity, North Tyrol had to import both wine and wheat. The interests of the farmers in the individual regions were completely different when it came to customs duties. The sovereign had to constantly strike a fine balance in order to satisfy all interests and necessities as best as possible. The Weinhaus Happ can be seen as a symbol of the differences in agriculture between Tyrol north and Tyrol south of the Brenner Pass, while at the same time the unity of the country is still felt by many people today.

Franz Baumann and Tyrolean modernism

The First World War not only brought ruling dynasties and empires to an end, the 1920s also saw many changes in art, music, literature and architecture. While jazz, atonal music and expressionism failed to establish themselves in little Innsbruck, a handful of architects changed the cityscape in an astonishing way. Inspired by new forms of design such as the Bauhaus style, skyscrapers from the USA and the Soviet Modernism from the revolutionary USSR, sensational projects emerged in Innsbruck. The best-known representatives of the avant-garde who brought about this new way of designing public space in Tyrol were Lois Welzenbacher, Siegfried Mazagg, Theodor Prachensky and Clemens Holzmeister. Each of these architects had their own idiosyncrasies, making the Tiroler Moderne is difficult to define clearly. What they all had in common was a departure from the classicist architecture of the pre-war period. Lois Welzenbacher wrote in 1920 in an article in the magazine Tyrolean highlands about the architecture of this period:

"As far as we can judge today, it is clear that the 19th century lacked the strength to create its own distinct style. It is the age of stillness... Thus details were reproduced with historical accuracy, mostly without any particular meaning or purpose, and without a harmonious overall picture that would have arisen from factual or artistic necessity."

The best-known and most impressive representative of the so-called Tiroler Moderne was Franz Baumann (1892 - 1974). Unlike Holzmeister or Welzenbacher, he had no academic training. Baumann was born in Innsbruck in 1892, the son of a postal clerk. The theologian, publicist and war propagandist Anton Müllner, alias Bruder Willram became aware of Franz Baumann's talent as a draughtsman and enabled the young man to attend the Staatsgewerbeschule, today's HTL, at the age of 14. It was here that he met his future brother-in-law Theodor Prachensky. Together with Baumann's sister Maria, the two young men went on excursions in the area around Innsbruck to paint pictures of the mountains and nature. During his school years, he gained his first professional experience as a bricklayer at the construction company Huter & Söhne. In 1910 Baumann followed his friend Prachensky to Merano to work for the company Musch & Lun to work. At the time, Merano was Tyrol's most important tourist resort with international spa guests. Under the architect Adalbert Erlebach, he gained his first experience in the planning of large-scale projects such as hotels and cable cars.

Like the majority of his generation, the First World War tore Baumann from his professional and everyday life. On the Italian front, he was shot in the stomach while fighting, from which he recovered in a military hospital in Prague. During this otherwise idle time, he painted cityscapes of buildings in and around Prague. These pictures, which would later help him to visualise his plans, were presented in his only exhibition in 1919.

Baumann's breakthrough came in the second half of the 1920s. He was able to win the tenders for the remodelling of the Weinhaus Happ in the old town and the Nordkettenbahn railway. In addition to his creativity and ability to think holistically, he was also able to harmonise his architectural approach with the legal situation and the modern requirements of tendering in the 1920s. Construction was a state matter, the Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association together with the district administration, was the final authority responsible for the assessment and authorisation of construction projects. During his time in Merano, Baumann was already involved with the Homeland Security Association came into contact with it. Kunibert Zimmeter had founded this association together with Gotthard Graf Trapp in the final years of the monarchy. In "Our Tyrol. A heritage book" he wrote:

"Let us look at the flattening of our private lives, our amusements, at the centre of which, significantly, is the cinema, at the literary ephemera of our newspaper reading, at the hopeless and costly excesses of fashion in the field of women's clothing, let us take a look at our homes with the miserable factory furniture and all the dreadful products of our so-called gallantry goods industry, Things that thousands of people work to produce, creating worthless bric-a-brac in the process, or let us look at our apartment blocks and villas with their cement façades simulating palaces, countless superfluous towers and gables, our hotels with their pompous façades, what a waste of the people's wealth, what an abundance of tastelessness we must find there."

The economic boom of the late 1920s saw the emergence of a new clientele and clientele that placed new demands on buildings and therefore on the construction industry. In many Tyrolean villages, hotels had replaced churches as the largest building in the townscape. The aristocratic distance from the mountains had given way to a bourgeois enthusiasm for sport. This called for new solutions at new heights. No more grand hotels were built at 1500 m for spa holidays, but a complete infrastructure for skiers in high alpine terrain such as the Nordkette. The Tyrolean Heritage Protection Association ensured that nature and townscape were protected from overly fashionable trends, excessive tourism and ugly industrial buildings. Building projects had to blend harmoniously, attractively and appropriately into the environment. Despite the social and artistic innovations of the time, architects had to keep the typical regional character in mind. This was precisely the strength of Baumann's approach to holistic building in the Tyrolean sense. All technical functions and details, the embedding of the buildings in the landscape, taking into account the topography and sunlight, played a role for him, who was not officially allowed to use the title of architect. He thus followed the "Rules for those who build in the mountains" by the architect Adolf Loos from 1913:

Don't build picturesquely. Leave such effects to the walls, the mountains and the sun. The man who dresses picturesquely is not picturesque, but a buffoon. The farmer does not dress picturesquely. But he is...

Pay attention to the forms in which the farmer builds. For they are ancestral wisdom, congealed substance. But seek out the reason for the mould. If advances in technology have made it possible to improve the mould, then this improvement should always be used. The flail will be replaced by the threshing machine."

Baumann designed even the smallest details, from the exterior lighting to the furniture, and integrated them into his overall concept of the Tiroler Moderne in.

From 1927, Baumann worked independently in his studio in Schöpfstraße in Wilten. He repeatedly came into contact with his brother-in-law and employee of the building authority, Theodor Prachensky. From 1929, the two of them worked together to design the building for the new Hötting secondary school on Fürstenweg. Although boys and girls still had to be planned separately in the traditional way, the building was otherwise completely in keeping with the style of the Neuen Sachlichkeit and the principle Light, air and sun.

In his heyday, he employed 14 people in his office. Thanks to his modern approach, which combined function, aesthetics and economical construction, he survived the economic crisis well. Only the 1000-mark barrierwhich Hitler imposed on Austria in 1934 in order to put the Republic in financial difficulties, caused problems for his architectural practice and the economy as a whole. Not only did the unemployment rate in tourism triple within a very short space of time, but the construction industry also got into difficulties. In 1935, Baumann became head of the Central Association of Architects after he was finally allowed to use this professional title with a special licence. In the same year, he planned the Hörtnaglsiedlung in the west of the city.

After the Anschluss in 1938, he quickly joined the NSDAP. On the one hand, like his colleague Lois Welzenbacher, he was probably not averse to the ideas of National Socialism, but on the other he was able to further his career as chairman of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in Tyrol. In this position, he courageously opposed the destructive furore with which those in power wanted to change Innsbruck's cityscape, which did not correspond to his idea of urban planning. The mayor of Innsbruck, Egon Denz, wanted to remove the Triumphal Gate and St Anne's Column in order to make more room for traffic in Maria-Theresienstraße. The city centre was still a transit area from the Brenner Pass in the south to reach the main road to the east and west on today's Innrain. At the request of Gauleiter Franz Hofer, a statue of Adolf Hitler was to be erected in place of St Anne's Column. Hofer also wanted to have the church towers of the collegiate church blown up. Baumann's opinion on these plans was negative. When the matter made it to Albert Speer's desk, he agreed with him. From this point onwards, Baumann was no longer awarded any public projects by Gauleiter Hofer.

After being questioned as part of the denazification process, Baumann began working at the city building authority, probably on the recommendation of his brother-in-law Prachensky. Baumann was fully exonerated, among other things by a statement from the Abbot of Wilten, whose church towers he had saved, but his reputation as an architect could no longer be repaired. Moreover, his studio in Schöpfstraße had been destroyed by a bomb in 1944. In his post-war career, he was responsible for the renovation of buildings damaged by the war. Under his leadership, Boznerplatz with the Rudolfsbrunnen fountain was rebuilt as well as Burggraben and the new Stadtsäle (Note: today House of Music).

Franz Baumann died in 1974 and his paintings, sketches and drawings are highly sought-after and highly traded. Anyone who takes a close look at recent major projects such as the city library, the PEMA towers and many of Innsbruck's housing estates will recognise the approaches of the Tiroler Moderne rediscover even today.

The Tyrolean nation, "democracy" and the heart of Jesus

Many tyroleans see themselves as an own nation. With „Tirol isch lei oans“, „Zu Mantua in Banden“ and „Dem Land Tirol die Treue", the federal state has three more or less official anthems. As in other federal states, there are historical reasons for this pronounced local patriotism. Tyrolean freedom and independence are often invoked as a local shrine to underpin this. It is often referred to as the first democracy in mainland Europe, which is probably an exaggeration considering the feudal and hierarchical history of the country up until the 20th century. However, the country cannot be denied a certain peculiarity in its development, even if it was less about the participation of broad sections of the population and more about the local elites curtailing the power of the sovereign.

The first act was what the Innsbruck historian Otto Stolz (1881 - 1957) in the 1950s exuberantly described, in reference to English history, as the Magna Charta Libertatum celebrated. After the marriage of the Bavarian Ludwig von Wittelsbach to the Tyrolean princess Margarete von Tirol-Görz, the Bavarian Wittelsbachs were rulers of Tyrol for a short time. In order to win over the Tyrolean population to his side, Ludwig decided to offer the provincial estates a treat in the 14th century. In the Großen Freiheitsbrief of 1342, Louis promised the Tyroleans that he would not enact any laws or tax increases without first consulting the provincial estates. However, there can be no question of a democratic constitution as understood in the 21st century, as these provincial estates were primarily the aristocratic, landowning classes, who represented their interests accordingly. Although one copy of the document mentioned the inclusion of peasants as a class in the Diet, this version never became official.

As the towns and bourgeoisie gained more political clout in the 15th century due to their economic importance, a counterweight to the nobility developed within the estates. At the Diet of 1423 under Frederick IV, 18 members of the nobility met 18 members of the towns and peasantry for the first time. Gradually, a fixed composition developed in the provincial diets of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Tyrolean bishops of Brixen and Trento, the abbots of the Tyrolean monasteries, the nobility, representatives of the towns and the peasantry were all represented. The provincial governor presided over the meeting. Of course, the resolutions and wishes of the provincial parliament were not binding for the prince, but it was probably a reassuring feeling for the ruler to know that the representatives of the population were on his side or that difficult decisions were supported.

Another important document for the country was the Tiroler Landlibell. In 1511, Maximilian stipulated, among other things, that Tyrolean soldiers should only be called up for military service in defence of their own country. The reason for Maximilian's generosity was less his love for the Tyroleans than the need to keep the Tyrolean mines running instead of burning out the precious labourers and the peasantry that supplied them on the battlefields of Europe. The fact that in Landlibell At the same time, massive restrictions on the population and higher costs are often forgotten. The Landlibell regulated not only the strength of the troop contingents but also the special taxes that were levied. The nobility and clergy had to use the capital gains from their estates as a tax base, which often amounted to a rough estimate. Towns, on the other hand, were taxed according to the number of fireplaces in the houses, which could be calculated quite accurately. Coveted miners were exempt from these taxes and only had to serve in the army in extreme emergencies.

This special regulation for national defence, as laid down in the Landlibell, was one of the reasons for the uprising of 1809, when young Tyroleans were conscripted for the mobilisation of the armed forces as part of general conscription. To this day, the Napoleonic Wars, when the Catholic crown land was threatened by the "godless French" and the revolutionary social order, characterise the Tyrolean self-image. During this defensive struggle, an alliance was formed between Catholicism and Tyrol. The Tyrolean marksmen entrusted their fate to the heart of Jesus before a decisive battle against Napoleon's armies in June 1796 and entered into a covenant with God personally, which would protect their Heiliges Land Tirol was supposed to protect her. Another identity-forming legend from 1796 centres around a young woman from the village of Spinges. Katharina Lanz, who was known as the Jungfrau von Spinges went down in the history of the country as an identity-forming national heroine, is said to have motivated the almost defeated Tyrolean troops with her imperious demeanour in battle to such an extent that they were ultimately able to achieve victory over the French superiority. Depending on the account, she is said to have taught Napoleon's troops to fear with a pitchfork, a flail or a scythe similar to the French Maid Joan of Arc. Legends and traditions surrounding the marksmen and the feeling of being an independent nation chosen by God, which happened to be attached to the Republic of Austria, go back to these legends.

The particular identities of the individual crown lands did not correspond to what enlightened politicians imagined a modern state to be. Under Maria Theresa, the central state was strengthened vis-à-vis the crown lands and the local nobility. The subjects' sense of belonging should not be to the province of Tyrol, but to the House of Habsburg. In the 19th century, the aim was to strengthen identification with the monarchy and develop a national consciousness. The press, visits by the ruling family, monuments such as the Rudolfsbrunnen or the opening of Mount Isel with Hofer as a Tyrolean loyal to the emperor were intended to help turn the population into subjects loyal to the emperor.

When the Habsburg Empire collapsed after the First World War, the crown land of Tyrol also broke up. What had been known as South Tyrol until 1918, the Italian-speaking part of the province between Riva on Lake Garda and Salurn in the Adige Valley, became Trentino with Trento as its capital. The German-speaking part of the province between Neumarkt and the Brenner Pass is now South Tyrol / Alto Adige, an autonomous region of the Republic of Italy with the capital Bolzano.

Throughout the centuries, Innsbruckers have felt themselves to be Tyroleans, Germans, Catholics and subjects of the emperor. Before 1945, however, hardly anyone felt Austrian. It was only after the Second World War that a sense of belonging to Austria slowly began to develop in Tyrol. To this day, however, many Tyroleans are proud of their local identity and like to distinguish themselves from the inhabitants of other federal states and countries. For many Tyroleans, after more than 100 years, the Brenner Pass still represents a Injustice limit even if the Europa der Regionen cooperates politically across borders at EU level.

The legend of the Holy Landthe independent Tyrolean nation and the first mainland democracy has survived to this day. The bon mot "bisch a Tiroler bisch a Mensch, bisch koana, bisch a Oasch" summarises Tyrolean nationalism succinctly. The fact that the historic crown land of Tyrol was a multi-ethnic construct with Italians, Ladins, Cimbrians and Rhaeto-Romans is often overlooked in right-wing circles. Laws from the federal capital of Vienna or even the EU in Brussels are still viewed with scepticism today. Nationalists on both sides of the Brenner Pass still make use of the Jungfrau von Spingesthe heart of Jesus and Andreas Hofer, to publicise their concerns. The Säcularfeier des Bundes Tirols mit dem göttlichen Herzen Jesu was still celebrated in the 20th century with great participation from the political elite.