The First World War and the time afterwards

The First World War

It was almost not Gavrilo Princip, but a student from Innsbruck who changed the fate of the world. It was thanks to chance that the 20-year-old Serb was stopped in 1913 because he bragged to a waitress that he was planning to assassinate the heir to the throne. It was only when the world-changing shooting in Sarajevo actually took place that an article about it appeared in the media. After the actual assassination of Franz Ferdinand on 28 June, it was impossible to foresee what impact the First World War that broke out as a result would have on the world and people's everyday lives. However, two days after the assassination of the Habsburg in Sarajevo, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten already prophetic: "We have reached a turning point - perhaps the "turning point" - in the fortunes of this empire".

Enthusiasm for the war in 1914 was also high in Innsbruck. From the "Gott, Kaiser und VaterlandDriven by the "spirit of the times", most people unanimously welcomed the attack on Serbia. Politicians, the clergy and the press joined in the general rejoicing. In addition to the imperial appeal "To my peoples", which appeared in all the media of the empire, the Innsbrucker Nachrichten On 29 July, the day after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, the media published an article about the capture of Belgrade by Prince Eugene in 1717. The tone in the media was celebratory, although not entirely without foreboding of what was to come.

"The Emperor's appeal to his people will be deeply felt. The internal strife has been silenced and the speculations of our enemies about unrest and similar things have been miserably put to shame. Above all, the Germans stand by the Emperor and the Empire in their old and well-tried loyalty: this time, too, they are ready to stand up for dynasty and fatherland with their blood. We are facing difficult days; no one can even guess what fate will bring us, what it will bring to Europe, what it will bring to the world. We can only trust with our old Emperor in our strength and in God and cherish the confidence that, if we find unity and stick together, we must be granted victory, for we did not want war and our cause is that of justice!"

Theologians such as Joseph Seeber (1856 - 1919) and Anton Müllner alias Bruder Willram (1870 - 1919) who, with her sermons and writings such as "Das blutige Jahr" elevated the war to a crusade against France and Italy.

Many Innsbruckers volunteered for the campaign against Serbia, which was thought to be a matter of a few weeks or months. Such a large number of volunteers came from outside the city to join the military commissions that Innsbruck was almost bursting at the seams. Nobody could have guessed how different things would turn out. Even after the first battles in distant Galicia, it was clear that it would not be a matter of months. Kaiserjäger and other Tyrolean troops were literally burnt out. Poor equipment, a lack of supplies and the catastrophic leadership of the high command under Konrad von Hötzendorf led to the deaths of thousands or to captivity, where hunger, abuse and forced labour awaited them.

In 1915, the Kingdom of Italy entered the war on the side of France and England. This meant that the front went right through what was then Tyrol. From the Ortler in the west across northern Lake Garda to the Sextener Dolomiten the battles of the mountain war took place. Innsbruck was not directly affected by the fighting. However, the war could at least be heard as far as the provincial capital, as was reported in the newspaper of 7 July 1915:

„Bald nach Beginn der Feindseligkeiten der Italiener konnte man in der Gegend der Serlesspitze deutlich Kanonendonner wahrnehmen, der von einem der Kampfplätze im Süden Tirols kam, wahrscheinlich von der Vielgereuter Hochebene. In den letzten Tagen ist nun in Innsbruck selbst und im Nordosten der Stadt unzweifelhaft der Schall von Geschützdonner festgestellt worden, einzelne starke Schläge, die dumpf, nicht rollend und tönend über den Brenner herüberklangen. Eine Täuschung ist ausgeschlossen. In Innsbruck selbst ist der Donner der Kanonen schwerer festzustellen, weil hier der Lärm zu groß ist, es wurde aber doch einmal abends ungefähr um 9 Uhr, als einigermaßen Ruhe herrschte, dieser unzweifelhafte von unseren Mörsern herrührender Donner gehört.“

Until the transfer of regular troops from the Eastern Front to the Tyrolean borders, the national defence depended on the Standschützen, a troop made up of men under 21, over 42 or unfit for regular military service. The casualty figures were correspondingly high.

Although the front was relatively far away from Innsbruck, the war also penetrated civilian life. Due to the mass mobilisation of a large part of the working male population, many businesses came to a complete standstill. Shelves in shops remained empty, public transport came to a standstill, craftsmen and labourers were missing everywhere. There was often a shortage of coal and firewood. Hunger and cold became bitter enemies of women, children, the wounded and those unfit for war in the city. This experience of the total involvement of society as a whole was new to the people. Barracks were erected in the Höttinger Au to house prisoners of war. Transports of wounded brought such a large number of horribly injured people that many civilian buildings such as the university library, which was currently under construction, or Ambras Castle were converted into military hospitals. The Pradl military cemetery was established to cope with the large number of fallen soldiers. A predecessor to tram line 3 was set up to transport the wounded from the railway station to the new garrison hospital, today's Conrad barracks in Pradl. The companies that were still able to produce were subordinated to the war economy. However, the longer the war lasted, the fewer there were. By the winter of 1917, Innsbruck's economy had almost completely collapsed.

As the war drew to a close, so did the front. In February 1918, the Italian air force managed to drop three bombs on Innsbruck. In this winter, which was known as Hunger winter When the war went down in European history, the shortages also made themselves felt. In the final years of the war, food was supplied via ration coupons. 500 g of meat, 60 g of butter and 2 kg of potatoes were the basic diet per person - per week, mind you. Archive photos show the long queues of desperate and hungry people outside the food shops. There were repeated protests and strikes. Politicians, trade unionists, workers and war returnees saw their chance for change. Under the motto Peace, bread and the right to vote a wide variety of parties united in resistance to the war. At this time, most people were already aware that the war was lost and what fate awaited Tyrol, as this article from 6 October 1918 shows:

„Aeußere und innere Feinde würfeln heute um das Land Andreas Hofers. Der letzte Wurf ist noch grausamer; schändlicher ist noch nie ein freies Land geschachert worden. Das Blut unserer Väter, Söhne und Brüder ist umsonst geflossen, wenn dieser schändliche Plan Wirklichkeit werden soll. Der letzte Wurf ist noch nicht getan. Darum auf Tiroler, zum Tiroler Volkstag in Brixen am 13. Oktober 1918 (nächsten Sonntag). Deutscher Boden muß deutsch bleiben, Tiroler Boden muß tirolisch bleiben. Tiroler entscheidet selbst über Eure Zukunft!“

On 4 November, Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Italy finally agreed an armistice. This gave the Allies the right to occupy areas of the monarchy. The very next day, Bavarian troops entered Innsbruck. Austria's ally Germany was still at war with Italy and was afraid that the front could be moved closer to the German Reich in North Tyrol. Fortunately for Innsbruck and the surrounding area, however, Germany also surrendered a week later on 11 November. This meant that the major battles between regular armies did not take place.

Nevertheless, Innsbruck was in danger. Huge columns of military vehicles, trains full of soldiers and thousands of emaciated soldiers making their way home from the front on foot passed through the city. Those who could, jumped on one of the overcrowded trains or a car to leave the Brenner Pass behind them to get home. In November 1918, more than 270 soldiers lost their lives during these daring manoeuvres or had to be admitted to one of the city's military hospitals. The city not only had to keep its own citizens in check and guarantee rations, but also protect itself from looting. In order to maintain public order, the Tyrolean National Council formed a People's Army on 5 November made up of schoolchildren, students, workers and citizens. On 23 November 1918, Italian troops occupied the city and the surrounding area. Mayor Greil's appeasement to the people of Innsbruck to surrender the city without rioting was successful. 5000 men had to find shelter in the starving and miserable city. Schools were turned into barracks. Although there were isolated riots, hunger riots and looting, there were no armed clashes with the occupying troops or even a Bolshevik revolution as in Munich.

Over 1200 Innsbruck residents lost their lives on the battlefields and in military hospitals, over 600 were wounded. Memorials to the First World War and its victims can be found in Innsbruck, particularly at churches and cemeteries. The Kaiserjägermuseum on Mount Isel displays uniforms, weapons and pictures of the battle. Streets in Innsbruck are dedicated to the two theologians Anton Müllner and Josef Seeber. A street was also named after the commander-in-chief of the Imperial and Royal Army on the Southern Front, Archduke Eugene. There is a memorial to the unsuccessful commander in front of the Hofgarten. The eastern part of the Amras military cemetery commemorates the Italian occupation.

"The assassination has been planned for years"

Published: Innsbrucker Nachrichten, 30 June 1914

The fact that the Greater Serbian agitators had been planning to assassinate the heir to the throne for years is best demonstrated by an episode that took place about a year and a half ago in Frankfurt and had its legal repercussions last summer.

The South Slavic students enrolled at the local medical faculty used to meet regularly in a pub in the centre of the city. Among the guests, 20-year-old Vistula Serbanovic from Belgrade claimed to be in favour with the beautiful girls there and to be popular. To make an impression on her, he told her that he belonged to a secret society that had set itself the task of travelling to Vienna and killing the Archduke there.

When the girl asked him, startled, whether he knew for sure about the plan, not only Serbanovic, but also ten of his friends wrote. The house searches that were carried out as a result of the number of enrolled Serbs of the young people involuntarily fished out at the entrance of any anti-partisan protocol had the result that the main participant managed to find a sharply loaded Browning, a Serbian flag and many detonators. During the interrogation, Serbanovic tried to claim that he had only spoken hearsay, but he substantiated it by saying that he had learnt this skill from a good high school student (Tonković or a Serbian commoner).

The Serbanovic trial, which as a minor was only partially investigated later, had little value due to the sensation; it ended with an acquittal because the defence succeeded in proving that the key witnesses were playing a joke that was poorly understood by the students at the time.

Nevertheless, the authorities maintained the view that Serbanovic was not a harmless fantasist after all, but a dangerous agent, and arranged for his expulsion from Austria. The Hungarian authorities did the same.

No one doubts that the young students were really part of a Serbian organisation that planned the murder in Sarajevo. It is also significant that Serbanovic, despite his young age, immediately rejoined a revolutionary organisation that encompassed the entire South Slavic youth.

To my peoples

This proclamation by Emperor Franz Josef I appeared in all the newspapers of the Empire on 29 July 1914, the day after the start of the war.

It was My most ardent wish to dedicate the years that are still granted to Me by God's grace to works of peace and to protect My peoples from the heavy sacrifices and burdens of war.

It was decided differently in the Council of Providence.

The machinations of a hateful adversary force Me to take up the sword after long years of peace in order to preserve the honour of My monarchy, to protect its reputation and its position of power, and to secure its possessions.

With quickly forgotten ingratitude, the Kingdom of Serbia, which had been supported and promoted by My ancestors and Me from the first beginnings of its state independence to the most recent times, set out on the path of open hostility against Austria-Hungary years ago.

When, after three decades of blessed peace work in Bosnia and Hercegovina, I extended My sovereign rights to these countries, this decree of Mine provoked outbursts of unbridled passion and bitter hatred in the Kingdom of Serbia, whose rights were in no way violated. At that time, My Government made use of the fine prerogative of the strongest and, with the utmost forbearance and leniency, demanded from Serbia only the reduction of its army to the level of peace and the promise to pursue the path of peace and friendship in the future.

Guided by the same spirit of moderation, my government, when Serbia was engaged in battle with the Turkish Empire two years ago, confined itself to safeguarding the most important living conditions of the monarchy. Serbia owed the achievement of the purpose of the war primarily to this attitude.

The hope that the Serbian kingdom would honour the patience and love of peace of my government and keep its word has not been fulfilled.

The hatred against Me and My House is flaring up ever higher, the endeavour to tear apart inseparable territories of Austria-Hungary by force is becoming more and more obvious.

Criminal activity is spreading across the border to undermine the foundations of state order in the south-east of the monarchy, to make the people, to whom I devote My full care in paternal love, waver in their loyalty to the ruling house and the fatherland, to mislead the growing youth and to incite them to sacrilegious acts of madness and high treason. A series of assassination attempts, a conspiracy prepared and carried out according to plan, the terrible success of which has struck Me and My people to the heart, forms the widely visible bloody trail of those secret machinations which were set in motion and directed from Serbia.

This intolerable activity must be stopped, an end must be put to Serbia's incessant challenges if the honour and dignity of My Monarchy are to be preserved intact and its state, economic and military development protected from constant upheaval.

In vain did my government make one last attempt to achieve this goal by peaceful means, to persuade Serbia to change its ways with a stern warning.

Serbia has rejected the moderate and just demands of My Government and refused to fulfil those duties whose fulfilment is the natural and necessary basis of peace in the life of peoples and states.

So I must then proceed to create the indispensable guarantees by force of arms, which are to secure peace within My states and lasting peace without.

In this serious hour I am fully aware of the full extent of My decision and My responsibility before the Almighty.

I have checked and considered everything.

With a clear conscience, I tread the path that duty shows me.

I trust in My peoples, who have always rallied around My throne in unity and loyalty in all storms and have always been prepared to make the heaviest sacrifices for the honour, greatness and power of the Fatherland.

I have faith in Austria-Hungary's valiant and enthusiastic armed forces.

And I trust in the Almighty that He will give victory to My weapons.

Sights to see...

Adolf-Pichler-Platz

Adolf-Pichler-Platz

Old & New Hötting Parish Church / Plague Cemetery

Schulgasse / Schneeburggasse

Adambräu & Ansitz Windegg

Adamgasse 23

Fraternity House Austria

Josef-Hirn-Straße

Johanneskirche

Bischof-Reinhold-Stecher-Platz

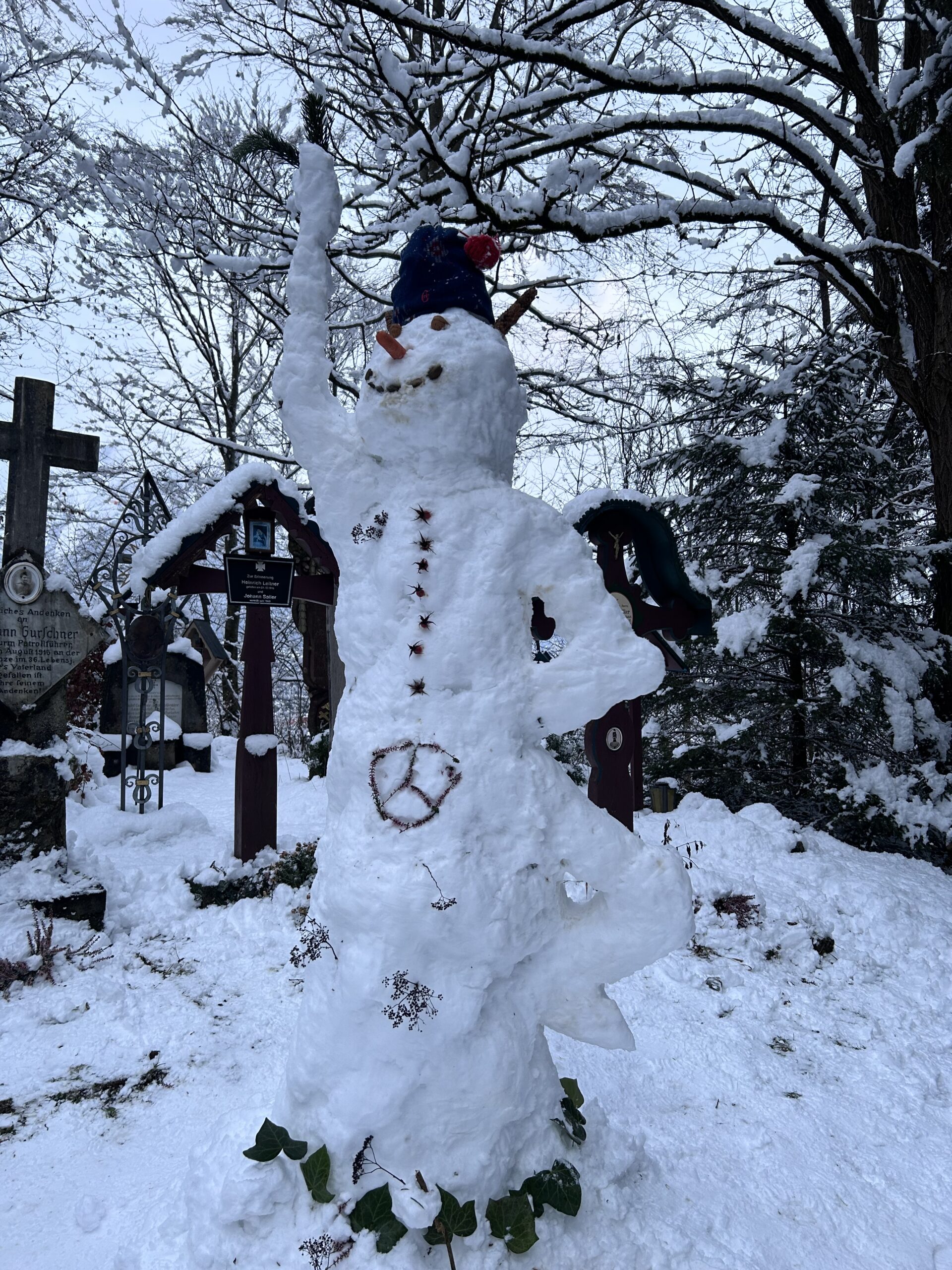

Militärfriedhof & Pradler Friedhof

Kaufmannstraße / Wiesengasse

Alter Militärfriedhof Pradl

Anzengruberstraße

Turnus clubhouse

Innstraße 2

St Nicholas Church & Cemetery

Schmelzergasse 1

University of Innsbruck

Innrain 52

Panoramagebäude

Rennweg 39

Tummelplatz

Haltestelle Tummelplatz