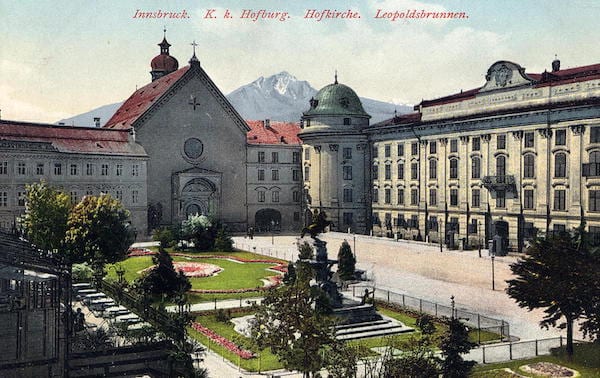

Court Church

Universitätsstraße 2

Worth knowing

„Das meiste Kunstinteresse erregt die Hof- oder Franziskaner-, eigentlich heil. Kreuzkirche, die mehr Museum der Erzbildnerei als Kirche ist. Im Mittelschiff ist das Grabmal Kaiser Marimilian’s I. angebracht, von einem unförmlichen Eisengitter umschlossen. Auf der Decke des Sargs ist der Kaiser lebensgroß, knieend, die Hände zum Gebet gefaltet, zu schauen. Diesen Erzguß verfertigte der Sicilianer Ludwig del Duca, und die an den vier Ecken der Decke angebrachten Statuetten, die Tugenden der Gerechtigkeit, Klugheit, Stärke und Mäßigkeit vorstellend… Die Seitenflächen des Sarges, in 24 Felder getheilt, enthalten auf eben so vielen Marmortafeln die merkwürdigsten Kriegs- und Friedensthaten dieses Herrschers in erhabener Arbeit.“

So beschrieb ein Besucher Innsbrucks im Jahr 1846 die Hofkirche. Und es ist wohl wahr: Kein Bauwerk zeigt die Sicht, die Maximilian I. auf sich selbst hatte, so gut wie die Innsbrucker Hofkirche. Der „letzte Ritter und erste Kanonier" placed himself at the centre of a long line of ancestors stretching back to the English legendary king Arthur. One could have gone even further, as Maximilian's court genealogist had identified Noah, the father of the Bible, and Hector, the prince of ancient Troy, as the progenitors of the Habsburgs.

Albrecht Dürer, among others, was involved in the design of the cenotaph, which is enthroned in the centre of the church. Dürer did not suffer the fate of many other early modern artists, whose value was only recognised post mortem, but marketed himself well during his lifetime. Maximilian was a keen patron of Dürer, who as a commercially and early capitalistically orientated artist was the cultural equivalent of the Fuggers.

Of the planned 40 Schwarzen Mandern, auch wenn nicht alle männlich sind, wurden schlussendlich nur 28 realisiert. Das Oratorium am Sarg von Hans Waldner stellt eine Sternstunde der Tischlereikunst dieser Zeit dar. Maximilian ließ sich knieend als frommer Mann darstellen. Die Reliefs an den Seiten zeigen wichtige Stationen aus dem Leben Maximilians, jedes für sich ist ein kleines Kunstwerk. Beginnend mit der Vermählung mit Maria von Burgund über verschiedene kriegerische Stationen zeigen die 24 Tafeln die Glanztaten Maximilians.

The emperor did not live to see the completion of his tomb. In 1519, at the end of his life, the Innsbruck innkeepers are said to have presented him with the bill that his court had accumulated over the years. Enraged by this insolence, Maximilian returned "seinem" Innsbruck and made his way to Wiener Neustadt, his alternative to Innsbruck as a final resting place. He died on the way there.

As the figures were too heavy for the castle in Wiener Neustadt, Emperor Ferdinand I, Maximilian's grandson, decided to have the tomb built in Innsbruck. The bronze figures were cast in the foundry opened in 1511 in the building in Mühlau now known as the Workers' House, and the empty coffin was nothing more than an unpleasant side effect. Construction of the church was completed in 1563 after 10 years.

Der Bau an der Kirche wurde 1563 nach 10 Jahren beendet. So egozentrisch Maximilian im Leben und dessen Darstellung war, so bescheiden wollte er seinen letzten Weg antreten. Er soll verfügt haben, ihn nach der letzten Ölung nicht mehr mit seinen Titeln anzusprechen, seinem Leichnam die Zähne zu ziehen, den Schädel zu rasieren und ihn in einen Leichensack einzunähen, auf dass er als armer Büßer vor dem Herrn im Himmel treten könnte. Glaube war ein Instrument, um Ordnung herzustellen und Macht zu legitimieren, Herrscher wie Maximilian waren aber keine Zyniker, sondern tatsächlich fromme Menschen. Glaube funktioniert nur, wenn man wirklich glaubt, Gebäude wie die Hofkirche zeigen das heute noch eindrucksvoll. Der Leichnam Maximilians wurde nicht mehr überführt, der Kaiser blieb in Wiener Neustadt begraben. Sein Herz wurde wie bei Monarchen üblich, getrennt vom Körper bestattet. Es liegt bei seiner geliebten ersten Ehefrau Maria von Burgund in Brügge. Die Schwarzmanderkirche ist auch ohne den Leichnam im prächtigen Sarkophag ein eindrucksvoller Coup des PR-Profis Maximilian. Sie gilt als das größte kaiserliche Grabmal Westeuropas.

Was dem Kaiser nicht gelang, schaffte der Tiroler Widerstandskämpfer Andreas Hofer. Seine sterblichen Überreste liegen in der Hofkirche in einem Ehrengrab. Nachdem er 1810 in Mantua hingerichtet worden war, machte sich eine inoffizielle Delegation der Tiroler Schützen 1823 auf, um den Leichnam Hofers auszugraben und nach Innsbruck zu überstellen. Nach anfänglichen Widerständen der Obrigkeit, wurde er schlussendlich doch in der Hofkirche beerdigt. Das Marmordenkmal zeigt Hofer in Tiroler Tracht mit Fahne beim Treueschwur „For God, Emperor and Fatherland".

At the back of the church, one of the oldest Renaissance organs that can still be played towers above the scenery. Instruments in churches are still used for concerts today, but hardly seem spectacular to us as 21st century people. We should not forget that church music was a highlight of the mass-goers' day for centuries, as there was no radio or Spotify.

Another sovereign of Tyrol is in the Silver Chapel which is accessible via the Hofkirche. Ferdinand II was regarded as a bon vivant, bon vivant and art collector. Given the stories about his legendary parties in the palace, it is hardly surprising that he was not buried with his second wife Caterina Gonzaga in the Servite Monastery, but with his first wife Philippine Welser, who was very popular with the people, in the Silver Chapel at the Innsbruck Hofburg.

Wer mehr über die Kultur und Alltag vergangener Zeiten in Tirol und die Geschichte der Hofkirche erfahren möchte, kann das Volkskunstmuseum im Rahmen der Besichtigung der Hofkirche besuchen. Das Volkskunstmuseum in Innsbruck war ehemals ein Stift, erbaut nach den Plänen von Andrea Crivelli und Niclas Türing, einem Mitglied der bedeutenden Tiroler Architektendynastie.

Maximilian I. und seine Zeit

Maximilian zählt zu den bedeutendsten Persönlichkeiten der europäischen und der Innsbrucker Stadtgeschichte. Über Tirol soll der passionierte Jäger gesagt haben: "Tirol ist ein grober Bauernkittel, der aber gut wärmt." Er machte Innsbruck in seiner Regierungszeit zu einem der wichtigsten Zentren des Heiligen Römischen Reichs. „Wer immer sich im Leben kein Gedächtnis macht, der hat nach seinem Tod kein Gedächtnis und derselbe Mensch wird mit dem Glockenton vergessen.“ Dieser Angst wirkte Maximilian höchst erfolgreich aktiv entgegen. Unter ihm spielten Propaganda, Bild und Medien eine immer stärkere Rolle, bedingt auch durch den aufkeimenden Buchdruck. Maximilian nutzte Kunst und Kultur, um sich präsent zu halten. So hielt er sich eine Reichskantorei, eine Musikkapelle, die vor allem bei öffentlichen Auftritten und Empfängen internationaler Gesandter zum Einsatz kam. Das Goldene DachlThe Hofburg, the Hofkirche and the Innsbruck Armoury were largely initiated by him, as was the paving of the streets and alleyways of the old town. He had the trade route laid in what is now Mariahilf and improved the city's water supply. Fire regulations had already existed in Innsbruck since 1510 and the new water pipeline, which had been laid to Innsbruck 25 years earlier under Maximilian, opened up new possibilities for fire protection. In 1499 Maximilian ordered the SalvatorikapelleHe began to rebuild a hospital for the needy inhabitants of Innsbruck, who had no right to a place in the Brotherhood's city hospital. He also began to chip away at the privileges of Wilten Abbey, the largest landowner in the present-day city area. Infrastructure owned by the monastery, such as the mill, sawmill and Sill Canal, were to come under greater control of the prince.

The imperial court, which was always based in Innsbruck, transformed Innsbruck's appearance and attitude. Envoys and politicians from all over Europe up to the Ottoman Empire as well as noblemen had their residences built in Innsbruck or stayed in the town's inns. Culturally, it was above all his second wife Bianca Maria Sforza who patronised Innsbruck. Not only did her wedding take place here, she also resided here for a long time, as the city was closer to her home in Milan than Maximilian's other residences. She brought her entire court with her from the Renaissance metropolis to the German lands north of the Alps.

Under Maximilian, Innsbruck not only became a cultural centre of the empire, the city also boomed economically. Among other things, Innsbruck was the centre of the postal service in the empire. The Thurn und Taxis family was granted a monopoly on this important service and chose Innsbruck as the centre of their private imperial postal service.

Maximilian was able to build on the expertise of the gunsmiths who had already established themselves in the foundries in Hötting under his predecessor Siegmund. The most famous of them was Peter "Löffler“ Laiminger. Die Geschichte der Löfflers ist im Roman Der Meister des siebten Siegels excellently processed.

The Fuggers maintained an office in Innsbruck. In addition to his favoured love of Tyrolean nature, the treasures such as salt from Hall and silver from Schwaz were at least as valuable and useful to him. Maximilian financed his lavish court, his election as king by the electors and his many wars by pledging the country's natural resources to the wealthy merchant family from Augsburg, among other things.

Maximilian was long unpopular with Tyrolean farmers during his lifetime. Maximilian curtailed the peasants' rights to the commons. Logging, hunting and fishing were placed under the control of the sovereign and were no longer common property. This had a negative impact on peasant self-sufficiency. Meat and fish, which had long been part of the diet in the Middle Ages, now became a luxury. It was around 1500 that hunters became poachers.

Many Tyroleans had to enforce the imperial will on the battlefields. Many of Maximilian's battles took place in the immediate vicinity of Tyrol. The wars demanded a great deal from the men fit for military service. This only changed in the last years of his reign. The skilful political move of the Tyrolean Landlibells from 1511 Maximilian was able to buy the affection and loyalty of his subjects and limit the influence of the bishops of Brixen and Trento. Maximilian conceded to the Tyroleans in a kind of constitution that they could only be called up as soldiers for the defence of their own country.

It is difficult to summarise Maximilian's work in Innsbruck. He is said to have been downright enamoured of his province of Tyrol. Of course, declarations of love from an emperor flatter the popular psyche to this day. His material legacy with its many magnificent buildings reinforces this positive image. He turned Innsbruck into an imperial residence city and pushed ahead with the modernisation of the infrastructure. Innsbruck became the centre of the armaments industry and grew economically and spatially. The debts he incurred for this and the state assets he pledged to the Fuggers left their mark on Tyrol after his death, at least as much as the strict laws he imposed on the ordinary population. In today's popular imagination, the hard times are not as present as the Goldene Dachl und die in der Schule gelernten weichen Fakten und Legenden rund um den einflussreichen Kaiser. 2019 überschlug man sich mit den Feierlichkeiten zum 500. Todestag des für Innsbruck wohl wichtigsten Habsburgers. Der Wiener wurde wohlwollend eingebürgert. Salzburg hat Mozart, Innsbruck Maximilian, einen Kaiser, den Tiroler, ob seiner damals nicht ungewöhnlichen Leidenschaft für die Jagd passend zur gewünschten Identität Innsbrucks als rauen Gesellen, der am liebsten in den Bergen ist, angepasst haben. Sein markantes Gesicht prangt heute auf allerhand Konsumartikeln, vom Käse bis zum Skilift steht der Kaiser für allerhand Profanes Pate. Lediglich für politische Agenden lässt er sich weniger gut vor den Karren spannen als Andreas Hofer. Wahrscheinlich ist es für den Durchschnittsbürger einfacher, sich mit einem revolutionären Wirt zu identifizieren als mit einem Kaiser.

Philippine Welser: Klein Venedig, Kochbücher und Kräuterkunde

Philippine Welser was the wife of Archduke Ferdinand II. The Welsers were one of the wealthiest non-aristocratic families of their time. Her uncle Bartholomäus Welser was similarly wealthy to Jakob Fugger. He had also granted loans to the Habsburgs. Instead of paying off the loans, Emperor Charles V pledged part of the newly annexed lands in America to the Welsers, who in return used the land as a colony. Klein-VenedigVenezuela, with fortresses and settlements. They organised expeditions to discover the legendary land of gold El Dorado to discover. In order to get as much as possible out of their fiefdom, they set up trading posts to take part in the profitable transatlantic slave trade between Europe, West Africa and America. Their brutal behaviour led to complaints at the imperial court, where they were subsequently stripped of their fiefdom.

Ferdinand and Philippine met at a carnival ball in Pilsen. The Habsburg fell head over heels in love with the wealthy woman from Augsburg and married her. Nobody in the House of Habsburg was particularly pleased about the couple's secret marriage, even though the Welser's money was put to good use. Despite their wealth, marriages between commoners and nobles were considered scandalous and not befitting their status. The children were therefore excluded from the succession.

Philippine galt als überaus schön. Ihre Haut sei laut Zeitzeugen so zart gewesen, „man hätte einen Schluck Rotwein durch ihre Kehle fließen sehen können". Ferdinand had Ambras Castle remodelled into its present form for his beloved wife. His brother Maximilian even said that "Ferdinand verzaubert sai" by the beautiful Philippine Welser, when Ferdinand withdrew his troops during the Turkish war to go home to his wife.

Philippine Welser's passion was cooking. A collection of recipes still exists in the Austrian National Library today. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the art of cookery was practised exclusively by the wealthy and nobility, while the vast majority of subjects had to eat whatever was available. The Middle Ages and modern times, in fact all people up until the 1950s, lived with a permanent lack of calories. Whereas today we eat too much and get ill as a result, our ancestors suffered from illnesses caused by malnutrition. Fruit was just as rare on the menu as meat. The food was monotonous and hardly flavoured. Spices such as exotic pepper were luxury goods that ordinary people could not afford. While the diet of the ordinary citizen was a dull affair, where the main aim was to get the calories for the daily work as efficiently as possible, the attitude towards food and drink began to change in Innsbruck under Ferdinand II and Philippine Welser. The court had contributed to a certain cultivation of manners and customs since Frederick IV, and Philippine Welser and Ferdinand continued to drive this development at Ambras Castle and Weiherburg Castle. The banquets they organised were legendary and often degenerated into orgies.

Herbalism was her second hobbyhorse. Philippine Welser described how plants and herbs could be used to alleviate physical ailments of all kinds. At Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, she had a herb garden created for her hobby and her studies.

According to reports of the time, she was very popular among the Tyrolean population, as she took great care of the poor and needy. The care of the needy, led by the town council and sponsored by wealthy citizens and aristocrats, was not a speciality at the time, but common practice. Closer to salvation in the next life than through Christian charity, Caritasyou could not come.

, konnte man nicht kommen. Ihre letzte Ruhe fand Philippine Welser nach ihrem Tod 1580 in der Silbernen Kapelle in der Innsbrucker Hofkirche. Gemeinsam mit ihren als Säugling verstorbenen Kindern und Ferdinand wurde sie dort begraben. Unterhalb des Schloss Ambras erinnert die Philippine-Welser-Straße an sie.

Ferdinand II.: Renaissance, Glanz und Glamour

Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria (1529 - 1595) is one of the most colourful figures in Tyrolean history. His father, Emperor Ferdinand I, gave his son an excellent education. He grew up at the Spanish court of his uncle Emperor Charles V. He spent part of his youth at the court in Innsbruck, which was also influenced by Spain at the time. The years in which Ferdinand received his schooling were the early years of Jesuit influence at the Habsburg courts. At a young age, he travelled through Italy and Burgundy and had become acquainted with a lifestyle at the wealthy courts there that had not yet established itself among the German aristocracy. Ferdinand was what today would be described as a globetrotter, a member of the educated elite or a cosmopolitan. He was considered intelligent, charming and artistic. Among his less eccentric contemporaries, Ferdinand enjoyed a reputation as an immoral and hedonistic libertine. Even during his lifetime, he was rumoured to have organised debauched and immoral orgies.

Ferdinand had taken over the province of Tyrol as sovereign in turbulent times. The mines in Schwaz began to become unprofitable due to the cheap silver from America. The flood of silver from the New World led to inflation. This did not stop him from maintaining an expensive court, while the cost of living rose for the poorer sections of the population. The Italian cities were style-defining in terms of culture, art and architecture. Ferdinand's Tyrolean court was in no way inferior to these cities. His masked balls and parades were legendary. Ferdinand had Innsbruck remodelled in the spirit of the Renaissance. In keeping with the trend of the time, he imitated the Italian aristocratic courts in Florence, Mantua, Ferrara and Milan. Court architect Giovanni Lucchese assisted him in this endeavour. Gone were the days when Germans in the more beautiful cities south of the Alps were regarded as uncivilised, barbaric or even as Pigs were labelled.

But Ambras Castle was not the end of the story. To the west of the town, an archway is a reminder of the Tiergarten, ein Jagdrevier Ferdinands samt Lusthaus entworfen ebenfalls von Lucchese. Damit der Landesfürst sein Wochenenddomizil erreichen konnte, wurde eine Straße in die sumpfige Höttinger Au gelegt, die die Basis für die heutige Kranebitter Allee bildete. Das Lusthaus wurde 1786 durch den heute als Pulverturm The new building, which houses part of the sports science faculty of the University of Innsbruck, replaced the well-known building. The princely sport of hunting was followed in the former Lusthaus, das der Pulverturm war, die Sportuniversität nach. In der Innenstadt ließ er das fürstliche Comedihaus am heutigen Rennweg errichten. Um Innsbrucks Trinkwasserversorgung zu verbessern, wurde unter Ferdinand die Mühlauerbrücke errichtet, um eine Wasserleitung vom Mühlaubach ins Stadtgebiet zu verlegen.

Ferdinand's politics were also influenced by Italy. Machiavelli wrote his work "Il Principe", which stated that rulers were allowed to do whatever was necessary for their success if they were incompetent and could be deposed. Ferdinand II attempted to do justice to this early absolutist style of leadership and issued a modern set of legal rules for the time with his Tyrolean Provincial Code. The Jesuits, who had arrived in Innsbruck shortly before Ferdinand took office to make life difficult for troublesome reformers and church critics, reorganise the education system and strengthen the church's presence, were given a new church in Silbergasse. It may seem contradictory today that the pleasure-seeking Prince Ferdinand defended the church as a Catholic and counter-reformer, but this was not the case in the late Renaissance period. With his measures against the Jewish population, he was also in line with the Jesuits.

Ferdinand spent a considerable part of his life at Ambras Castle near Innsbruck, where he amassed one of the most valuable collections of works of art and armour in the world.

Ferdinand's first "semi-wild marriage" was to the commoner Philippine Welser. The sovereign is said to have been downright infatuated with his beautiful wife, which is why he disregarded all conventions of the time. Their children were excluded from the succession due to the strict social order of the 16th century. After Philippine Welser died, Ferdinand married the devout Anna Caterina Gonzaga, a 16-year-old princess of Mantua, at the age of 53. However, it seems that the two did not feel much affection for each other, especially as Anna Caterina was a niece of Ferdinand. The Habsburgs were less squeamish about marriages between relatives than they were about the marriage of a nobleman to a commoner. However, he was also "only" able to father three daughters with her. Ferdinand found his final resting place in the Silver Chapel with his first wife.

Andreas Hofer and the Tyrolean uprising of 1809

The Napoleonic Wars gave the province of Tyrol a national epic and a hero whose splendour still shines today. The reason for this was once again a conflict with its northern neighbour and its allies after 1703. During the Napoleonic Wars, the Kingdom of Bavaria was, as it had been during the War of the Spanish Succession allied with France and was able to conquer Tyrol between 1796 and 1805. Innsbruck was no longer the provincial capital of Tyrol, but only one of many district capitals of the administrative unit Innkreis.

Taxes were increased and powers reduced. Processions and religious festivals of the conservative and pious Tyroleans fell victim to the Enlightenment programme of the new rulers, who were influenced by the French Revolution. Strict Catholics like Father Haspinger were also opposed to measures such as the smallpox vaccinations ordered by the Bavarians. There was great dissatisfaction among large sections of the Tyrolean population.

The spark that set off the powder keg was the conscription of young men for service in the Bavarian-Napoleonic army, although Tyroleans had been in the army since the LandlibellThe law of Emperor Maximilian stipulated that soldiers could only be called up for the defence of their own borders. On 10 April, there was a riot during a conscription in Axams near Innsbruck, which ultimately led to an uprising.

For God, Emperor and Fatherland Tyrolean defence units came together to drive the small army and the Bavarian administrative officials out of Innsbruck. The riflemen were led by Andreas Hofer (1767 - 1810), an innkeeper, wine and horse trader from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley near Meran. He was supported not only by other Tyroleans such as Father Haspinger, Peter Mayr and Josef Speckbacher, but also by the Habsburg Archduke Johann in the background.

Once in Innsbruck, the marksmen plundered houses, some of whose liberal inhabitants were not entirely averse to the modern Bavarian administration. Some of the citizens would have preferred this fresh wind blowing over from revolutionary France to the conservative Habsburgs. The wild mob was probably more harmful to the city than the Bavarian administrators had been since 1805, and the "liberators" rioted violently against Innsbruck's small Jewish population in particular.

One month later, the Bavarians and French had regained control of Innsbruck. What followed was what was known as the Tyrolean survey under Andreas Hofer, who had meanwhile assumed supreme command of the Tyrolean defence forces, was to go down in the history books. The Tyrolean insurgents were able to carry victory from the battlefield a total of three times. The 3rd battle in August 1809 on Mount Isel is particularly well known. "Innsbruck sees and hears what it has never heard or seen before: a battle of 40,000 combatants...“

For a short time, Andreas Hofer was Tyrol's commander-in-chief in the absence of regular facts, also for civil matters. Innsbruck had to bear the costs of board and lodging for this peasant regiment. The city's liberal and wealthy circles in particular were not happy with the new city rulers. The decrees issued by him as provincial commander were more reminiscent of a theocracy than a 19th century body of laws. Women were only allowed to go out on the streets wearing a chaste veil, dance events were banned and revealing monuments such as the one on the Leopoldsbrunnen nymphs on display were banned from public spaces. Educational agendas were to return to the clergy. Liberals and intellectuals were arrested, but the Praying the rosary to the bid.

In the end, the fourth and final battle on Mount Isel in autumn 1809 resulted in a heavy defeat against the French superiority. The government in Vienna had used the Tyrolean rebels primarily as a tactical bruiser in the war against Napoleon. The Emperor had already had to officially cede the province of Tyrol in the peace treaty of Schönbrunn. Innsbruck was again under Bavarian administration between 1810 and 1814. By this time, Hofer himself was already a man marked by the effects of alcohol. He was captured and executed in Mantua on 20 January 1810.

Der „Fight for freedom" symbolises the Tyrolean self-image to this day. For a long time, Andreas Hofer, the innkeeper from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley, was regarded as an undisputed hero and the prototype of the Tyrolean who was brave, loyal to his fatherland and steadfast. The underdog who fought back against foreign superiority and unholy customs. In fact, Hofer was probably a charismatic leader, but politically untalented and conservative-clerical, simple-minded. His tactics at the 3rd Battle of Mount Isel "Do not abandon them" (Ann.: You just mustn't let them come up) probably summarises his nature quite well.

In conservative Tyrolean circles such as the Schützen, Hofer is uncritically and cultishly worshipped. Tyrolean marksmanship is a living tradition that has modernised, but is still reactionary in many dark corners. Wiltener, Amraser, Pradler and Höttinger marksmen still march in unison alongside the clergy, traditional costume societies and marching bands in church processions and shoot into the air to keep all evil away from Tyrol and the Catholic Church.

In Tyrol, Andreas Hofer is still used today for all kinds of initiatives and plans. The glorified hero Andreas Hofer was repeatedly invoked, especially during the nationalist period of the 19th century. Hofer was stylised into an icon through paintings, pamphlets and plays. But even today, you can still see the likeness of the head marksman when Tyroleans defend themselves against unwelcome measures by the federal government, the transit regulations of the EU or FC Wacker against foreign football clubs. The motto is then "Man, it's time!". The legend of the Tyrolean farmer who is fit for military service, who tills the fields during the day and trains as a marksman and defender of his homeland at the shooting range in the evening, is often brought out of the drawer to strengthen the "real" Tyrolean identity.

It was only in the last few decades that the arch-conservative and probably overburdened with his task as Tyrolean provincial commander began to be criticised. Spurred on by parts of the Habsburgs and the Catholic Church, he not only wanted to keep the French and Bavarians out of Tyrol, but also the liberal ideas of the Enlightenment.

Many monuments throughout the city commemorate the year 1809. Andreas Hofer and his comrades-in-arms Josef Speckbacher, Peter Mayer, Father Haspinger and Kajetan Sweth were given street names, especially in the Wilten district, which became part of Innsbruck in 1904 and had long been under the administration of the monastery. To this day, the celebrations to mark the anniversary of Andreas Hofer's death on 20 February regularly attract crowds of people from all parts of Tyrol to the city.

Believe, Church and Power

The abundance of churches, chapels, crucifixes and murals in public spaces has a peculiar effect on many visitors to Innsbruck from other countries. Not only places of worship, but also many private homes are decorated with depictions of the Holy Family or biblical scenes. The Christian faith and its institutions have characterised everyday life throughout Europe for centuries. Innsbruck, as the residence city of the strictly Catholic Habsburgs and capital of the self-proclaimed Holy Land of Tyrol, was particularly favoured when it came to the decoration of ecclesiastical buildings. The dimensions of the churches alone are gigantic by the standards of the past. In the 16th century, the town with its population of just under 5,000 had several churches that outshone every other building in terms of splendour and size, including the palaces of the aristocracy. Wilten Monastery was a huge complex in the centre of a small farming village that was grouped around it. The spatial dimensions of the places of worship reflect their importance in the political and social structure.

For many Innsbruck residents, the church was not only a moral authority, but also a secular landlord. The Bishop of Brixen was formally on an equal footing with the sovereign. The peasants worked on the bishop's estates in the same way as they worked for a secular prince on his estates. This gave them tax and legal sovereignty over many people. The ecclesiastical landowners were not regarded as less strict, but even as particularly demanding towards their subjects. At the same time, it was also the clergy in Innsbruck who were largely responsible for social welfare, nursing, care for the poor and orphans, feeding and education. The influence of the church extended into the material world in much the same way as the state does today with its tax office, police, education system and labour office. What democracy, parliament and the market economy are to us today, the Bible and pastors were to the people of past centuries: a reality that maintained order. To believe that all churchmen were cynical men of power who exploited their uneducated subjects is not correct. The majority of both the clergy and the nobility were pious and godly, albeit in a way that is difficult to understand from today's perspective.

Unlike today, religion was by no means a private matter. Violations of religion and morals were tried in secular courts and severely penalised. The charge for misconduct was heresy, which encompassed a wide range of offences. Sodomy, i.e. any sexual act that did not serve procreation, sorcery, witchcraft, blasphemy - in short, any deviation from the right belief in God - could be punished with burning. Burning was intended to purify the condemned and destroy them and their sinful behaviour once and for all in order to eradicate evil from the community.

For a long time, the church regulated the everyday social fabric of people down to the smallest details of daily life. Church bells determined people's schedules. Their sound called people to work, to church services or signalled the death of a member of the congregation. People were able to distinguish between individual bell sounds and their meaning. Sundays and public holidays structured the time. Fasting days regulated the diet. Family life, sexuality and individual behaviour had to be guided by the morals laid down by the church. The salvation of the soul in the next life was more important to many people than happiness on earth, as this was in any case predetermined by the events of time and divine will. Purgatory, the last judgement and the torments of hell were a reality and also frightened and disciplined adults.

While Innsbruck's bourgeoisie had been at least gently kissed awake by the ideas of the Enlightenment after the Napoleonic Wars, the majority of people in the surrounding communities remained attached to the mixture of conservative Catholicism and superstitious popular piety.

Faith and the church still have a firm place in the everyday lives of Innsbruck residents, albeit often unnoticed. The resignations from the church in recent decades have put a dent in the official number of members and leisure events are better attended than Sunday masses. However, the Roman Catholic Church still has a lot of ground in and around Innsbruck, even outside the walls of the respective monasteries and educational centres. A number of schools in and around Innsbruck are also under the influence of conservative forces and the church. And anyone who always enjoys a public holiday, pecks one Easter egg after another or lights a candle on the Christmas tree does not have to be a Christian to act in the name of Jesus disguised as tradition.

Maria Theresia, Reformatorin und Landesmutter

Maria Theresa is one of the most important figures in Austrian history. Although she is often referred to as Empress, she was officially "only" Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Queen of Bohemia. Her domestic reforms were significant. Together with her advisors Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, Joseph von Sonnenfels and Wenzel Anton Kaunitz, she managed to emerge from the so-called Österreichischen Erblanden to create a modern state. Instead of the administration of its territories by the local nobility, it favoured a modern administration. The welfare of her subjects became more important. In the style of the Enlightenment, her advisors had recognised that the welfare of the state depended on the health and education of its individual parts. Subjects were to be Catholic, but their loyalty was to be to the state. School education was placed under centralised state administration. No critical, humanistic intellectuals were to be educated, but rather material for the state administrative apparatus. Non-nobles could now also rise to higher state positions via the military and administration.

A rethink took place in law enforcement and the judiciary. In 1747, a kleine Polizei which was responsible for matters relating to market supervision, trade regulations, tourist control and public decency. The penal code Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana did not abolish torture, but it did regulate its use.

Economic reforms were intended not only to create more opportunities for the subjects, but also to increase state revenue. Weights and measures were nominated to make the tax system more impermeable. For citizens and peasants, the standardisation of laws had the advantage that life was less dependent on landlords and their whims. The RobotThis was abolished under Maria Theresa.

As much as Maria Theresa staged herself as a pious mother of the country and is known today as an Enlightenment figure, the strict Catholic ruler was not squeamish when it came to questions of power and religion. In keeping with the trend of the Enlightenment, she had superstitions such as vampirism, which was widespread in the eastern parts of her empire, critically analysed and initiated the final end to witch trials. At the same time, however, she mercilessly expelled Protestants from the country. Many Tyroleans were forced to leave their homeland and settle in parts of the Habsburg Empire further away from the centre.

In crown lands such as Tyrol, Maria Theresa's reforms met with little favour. With the exception of a few liberals, they saw themselves more as an independent and autonomous province and less as part of a modern territorial state. The clergy also did not like the new, subordinate role, which became even more pronounced under Joseph II. For the local nobility, the reforms not only meant a loss of importance and autonomy, but also higher taxes and duties. Taxes, levies and customs duties, which had always provided the city of Innsbruck with reliable income, were now collected centrally and only partially refunded via financial equalisation. In order to minimise the fall of sons from impoverished aristocratic families and train them for civil service, Maria Theresa founded the Theresianumwhich also had a branch in Innsbruck from 1775.

As is so often the case, time has ironed out many a wrinkle and the people of Innsbruck are now proud to have been home to one of the most important rulers in Austrian history. Today, the Triumphpfote and the Hofburg in Innsbruck are the main reminders of the Theresian era.

Innsbruck and the House of Habsburg

Today, Innsbruck's city centre is characterised by buildings and monuments that commemorate the Habsburg family. For many centuries, the Habsburgs were a European ruling dynasty whose sphere of influence included a wide variety of territories. At the zenith of their power, they were the rulers of a "Reich, in dem die Sonne nie untergeht". Through wars and skilful marriage and power politics, they sat at the levers of power between South America and the Ukraine in various eras. Innsbruck was repeatedly the centre of power for this dynasty. The relationship was particularly intense between the 15th and 17th centuries. Due to its strategically favourable location between the Italian cities and German centres such as Augsburg and Regensburg, Innsbruck was given a special place in the empire at the latest after its elevation to the status of a royal seat under Emperor Maximilian. Some of the Habsburg rulers had no special relationship with Tyrol, nor did they have any particular affection for this German land. Ferdinand I (1503 - 1564) was educated at the Spanish court. Maximilian's grandson Charles V had grown up in Burgundy. When he set foot on Spanish soil for the first time at the age of 17 to take over his mother Joan's inheritance of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, he did not speak a word of Spanish. When he was elected German Emperor in 1519, he did not speak a word of German.

Tyrol was a province and, as a conservative region, usually favoured by the ruling family. Its inaccessible location made it the perfect refuge in troubled and crisis-ridden times. Charles V (1500 - 1558) fled during a conflict with the Protestant Schmalkaldischen Bund to Innsbruck for some time. Ferdinand I (1793 - 1875) allowed his family to stay in Innsbruck, far away from the Ottoman threat in eastern Austria. Shortly before his coronation in the turbulent summer of the 1848 revolution, Franz Josef I enjoyed the seclusion of Innsbruck together with his brother Maximilian, who was later shot by insurgent nationalists as Emperor of Mexico. A plaque at the Alpengasthof Heiligwasser above Igls reminds us that the monarch spent the night here as part of his ascent of the Patscherkofel.

Not all Habsburgs were always happy to be in Innsbruck. Married princes and princesses such as Maximilian's second wife Bianca Maria Sforza or Ferdinand II's second wife Anna Caterina Gonzaga were stranded in the harsh, German-speaking mountains after their wedding without being asked. If you also imagine what a move and marriage from Italy to Tyrol to a foreign man meant for a teenager, you can imagine how difficult life was for the princesses. Until the 20th century, children of the aristocracy were primarily brought up to be politically married. There was no opposition to this. One might imagine courtly life to be ostentatious, but privacy was not provided for in all this luxury.

When Sigismund Franz von Habsburg (1630 - 1665) died childless as the last prince of the province, the title of royal seat was also history and Tyrol was ruled by a governor. Tyrolean mining had lost its importance. Shortly afterwards, the Habsburgs lost their possessions in Western Europe along with Spain and Burgundy, moving Innsbruck from the centre to the periphery of the empire. In the Austro-Hungarian monarchy of the 19th century, Innsbruck was the western outpost of a huge empire that stretched as far as today's Ukraine. Franz Josef I (1830 - 1916) ruled over a multi-ethnic empire between 1848 and 1916. However, his neo-absolutist concept of rule was out of date. Although Austria had had a parliament and a constitution since 1867, the emperor regarded this government as "his". Ministers were responsible to the emperor, who was above the government. The ailing empire collapsed in the second half of the 19th century. On 28 October 1918, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was proclaimed, and on 29 October, Croats, Slovenes and Serbs left the monarchy. The last Emperor Charles abdicated on 11 November. On 12 November, "Deutschösterreich zur demokratischen Republik, in der alle Gewalt vom Volke ausgeht“. The chapter of the Habsburgs was over.

Despite all the national, economic and democratic problems that existed in the multi-ethnic states that were subject to the Habsburgs in various compositions and forms, the subsequent nation states were sometimes much less successful in reconciling the interests of minorities and cultural differences within their territories. Since the eastward enlargement of the EU, the Habsburg monarchy has been seen by some well-meaning historians as a pre-modern predecessor of the European Union. Together with the Catholic Church, the Habsburgs shaped the public sphere through architecture, art and culture. Goldenes DachlThe Hofburg, the Triumphal Gate, Ambras Castle, the Leopold Fountain and many other buildings still remind us of the presence of the most important ruling dynasty in European history in Innsbruck.