Leopoldsbrunnen

University Road 1

Worth knowing

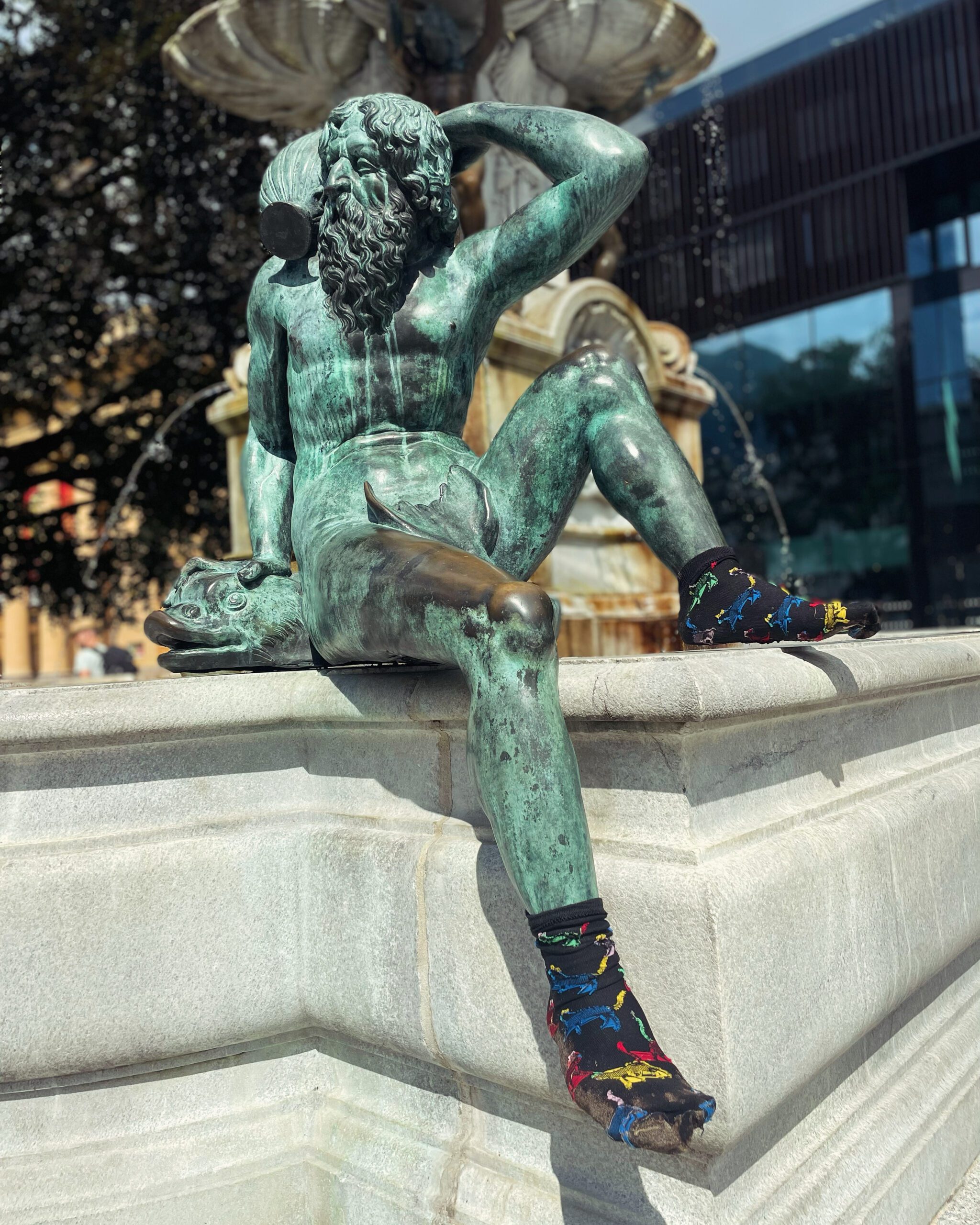

The Baroque Leopold Fountain in front of the Tyrolean State Theatre and the House of Music commemorates the Habsburg Leopold V. Greek gods and nymphs pose around the edge of the basin. Artemis, with her gesture, is particularly popular among tourists and locals as a photo buddy, appearing like the supposed inventor of the selfie. The Innsbruck court aimed to emulate the Italian princely courts that set the trends by adopting this reference to antiquity. Above all, Leopold towers, portrayed in the style of a Roman emperor as a victorious commander. The special feature of his equestrian statue is that the horse stands upright without “supporting” itself on its tail. A lead weight in the tail ensures that horse and rider do not topple over. At the time of its creation, this courbette was a sensation, as it was the only bronze sculpture of a rearing horse of this kind north of the Alps without any supporting aid.

When the Tyrolean sovereign died in 1632, the fountain was still unfinished. During his lifetime, the figures were placed along Rennweg in front of the Hofburg and in the princely court garden. It would take another 250 years for the final work to be completed. The occasion for finishing the fountain was the Tyrolean State Exhibition held in Innsbruck in June 1893. The installation and design of the fountain were entrusted to the skilled hands of Johann Deiniger and Heinrich Fuss, founders of the Imperial-Royal State Trade School, today’s HTL Anichstraße. About ten years earlier, their new educational institution had welcomed its first students. Strengthening local crafts and industry was the order of the day, and the new type of school and modern trade fair were intended to contribute to this goal. The state exhibition aimed not only to present “Tyrol with an image of its entire agricultural, industrial, technical, and artistic capabilities” but also to demonstrate the crown land’s loyalty to the monarchy. Leopold V was the ideal Habsburg for this occasion and the spirit of the turn of the century, which was architecturally shaped by neoclassicism. The ancient Greek world of gods combined with the powerful Habsburg prince was a perfect match to adorn the square in front of the theatre in a way that was both national-liberal and loyal to the emperor. The Renaissance-style artworks fit the year 1893 at least as well as they did the early modern period—at least from the perspective of Innsbruck’s educated bourgeoisie. Leopold was considered a liberal bon vivant who had renounced the clergy and bishopric to serve his homeland. The Innsbrucker Nachrichten described the opening with the following words:

"The actual opening ceremony began in the exhibition hall at 11am. A coat of arms - the Tyrolean eagle with the imperial motto "Viribus unitis" below it - adorned the pediment of the entrance. Palm trees and mighty bamboo sticks adorned the portal. The guests gathered in the centre of the hall by the Leopoldsbrunnen fountain in front of the magnificent imperial tent."

As is typical of monuments in public spaces to this day—especially when a political message resonates—the Leopold Fountain was also controversial. In the year of its installation, it was a hot political issue. The press even spoke of a “fountain war” surrounding the monument. In a carnival speech, the Leopold Fountain was mockingly referred to as a monumental stove. The uproar was not new. Nearly 100 years earlier, the figures of the fountain had almost met their end. When Andreas Hofer resided in Innsbruck as Tyrol’s commander in 1809, the overly revealing figures were a thorn in his side. The devout Catholic wanted to hide the bare-breasted nymphs and the polytheism of antiquity from the eyes of the hoped-for pious population. He planned to melt down the bronze statues to make cannon ammunition. Thanks to some Innsbruck citizens who hid the artworks, the Leopold Fountain still exists today. The “fountain war” continues to this day. More often than other artworks, the statues invite pranksters to decorate them with clothing and other adornments. In 2022, one of the nymphs was even unscrewed and stolen from the fountain. Although the originals had long been housed in the Ferdinandeum and it was only a copy, the disappearance of the statue became the talk of the town. After weeks of speculation about the crime, during which countless rumors about motives and perpetrators circulated, the figure reappeared on the bike path in the Olympic Village. Whether it was an imitator and admirer of moral guardian Andreas Hofer or just a “drunken escapade” will probably never be clarified.

Leopold V & Claudia de Medici: Glamour and splendour in Innsbruck

The most important princely couple for the Baroque face of Innsbruck ruled Tyrol during the period in which the Thirty Years' War devastated Europe. The Habsburg Leopold (1586 - 1632) to lead the princely affairs of state in the Upper Austrian regiment in Tyrol and the foothills. He had enjoyed a classical education under the wing of the Jesuits. He studied philosophy and theology in Graz and Judenburg in order to prepare himself for the clerical realm of power politics, a common career path for later-born sons who had little chance of ascending to secular thrones. Leopold's early career in the church's power structure epitomised everything that Protestants and church reformers rejected about the Catholic Church. At the age of 12, he was elected Bishop of Passau, and at thirteen he was appointed coadjutor of the diocese of Strasbourg in Lorraine. However, he never received ecclesiastical ordination. His prince-bishop was responsible for his spiritual duties. He was a passionate politician, travelled extensively between his dioceses and took part on the imperial side in the conflict between Rudolf II and Matthias, the model for Franz Grillparzer's "Fraternal strife in the House of Habsburg". These agendas, which were not necessarily an honour for a churchman, were intended to keep Leopold's chances of becoming a secular prince alive.

This opportunity came when the unmarried Maximilian III died childless in 1618. At the behest of his brother, Leopold acted as the Habsburg Governor and regent of these Upper and Vorderösterreichische, also Mitincorpierter Leuth and Lannde. In his first years as regent, he continued to commute between his bishoprics in southern and western Germany, which were threatened by the turmoil of the Thirty Years' War. The ambitious power politician was probably satisfied with his exciting life in the midst of high politics, but not with his status as gubernator. He wanted the title of Prince Regnant along with homage and dynastic hereditary rights. He lacked a suitable bride, time and money for the title of prince and to set up a court. The costly disputes in which he was involved had emptied Leopold's coffers.

The money came with the bride and with it came time. Claudia de Medici (1604 - 1648) from the rich Tuscan family of merchants and princes was chosen to bring dynastic delights to the future sovereign, who was already approaching 40. Claudia had already been promised to the Duke of Urbino as a child, whom she married at the age of 17 despite a request from Emperor Ferdinand II. After two years of marriage, her husband died. The ties with the Habsburgs were still there. The two dynasties had been closely intertwined since the marriage of Francesco de Medici to Joan of Habsburg, a daughter of Ferdinand I. at the latest. Leopold and Claudia were also a Perfect Match of title, power, baroque piety and money. Leopold's sister Maria Magdalena had landed in Florence as Grand Duchess of Tuscany by marriage and sent her brother a painted portrait of the young widow Claudia with the accompanying words that she "beautiful in face, body and virtue" be. After a chicken-and-egg dance - the bride's family wanted an assurance of the son-in-law's titles while his brother the emperor demanded proof of a bride for the award of the ducal dignity - the time had come. In 1625, Leopold, now elevated to duke, well-fed and forty years old, renounced his ecclesiastical possessions and dignities in order to marry and found a new Tyrolean line of the House of Habsburg with his bride, who was almost 20 years his junior.

The relationship between the prince and the Italian woman was to characterise Innsbruck. The Medici had made a fortune from the cotton and textile trade, but above all from financial transactions, and had risen to political power. Under the Medici, Florence had become the cultural and financial centre of Europe, comparable to the New York of the 20th century or the Arab Emirates of the 21st century. The Florentine cathedral, which was commissioned by the powerful wool merchants' guild, was the most spectacular building in the world in terms of its design and size. Galileo Galilei was the first mathematician of Duke Cosimo II. In 1570, Cosimo de Medici was appointed the first Grand Duke of Tuscany by the Pope. Thanks to generous loans and donations, the Tuscan moneyed aristocracy became European aristocracy. In the 17th century, the city on the Arno had lost some of its political clout, but in cultural terms Florence was still the benchmark. Leopold did everything in his power to catapult his royal seat into this league.

In February 1622, the wedding celebrations between Emperor Ferdinand II and Eleanor of Mantua took place in Innsbruck. Innsbruck was easier to reach than Vienna for the bridal party from northern Italy. Tyrol was also denominationally united and had been spared the first years of the Thirty Years' War. While the imperial wedding was completed in five days, Leopold and Claudia's party lasted over two weeks. The official wedding took place in Florence Cathedral without the presence of the groom. The subsequent celebration in honour of the union of Habsburg and Medici went down as one of the most magnificent in Innsbruck's history and kept the city in suspense for a fortnight. After a frosty entry from the snow-covered Brenner Pass, Innsbruck welcomed its new princess and her family. The husband and his subjects had prayed in advance for divine blessing to purify themselves. Like the Emperor before them, the bridal couple entered the city in a long procession through two specially erected gates. 1500 marksmen fired volleys from all guns. Drummers, pipers and the bells of the Hofkirche accompanied the procession of 750 people as they marvelled at the crowd. A broad entertainment programme with hunts, theatre, dances, music and all kinds of exotic events such as "Bears, Türggen and Moors" left guests and townspeople in raptures and amazement. From today's perspective, a less glamorous highlight was the Cat racein which several riders attempted to chop off the head of a cat hanging by its legs as it rode past.

Leopold's early years in power were less glorious for his subjects. His politics were characterised by many disputes with the estates. As a hardliner of the Counter-Reformation, he was a supporter of the imperial troops. The Lower Engadine, over which Leopold had jurisdiction, was a constant centre of unrest. Under the pretext of protecting the Catholic subjects living there from Protestant attacks, Leopold had the area occupied. Although he was always able to successfully suppress uprisings, the resources required to do so infuriated the population and the estates. The situation on the northern border with Bavaria was also unsettled and required Leopold as warlord. Duke Bernhard of Weimar had taken Füssen and was at the Ehrenberger Klause on the border. Although Innsbruck was spared direct hostilities, it was still part of the Thirty Years' War thanks to the nearby front lines.

He provided the financial means for this through a comprehensive tax reform to the detriment of the middle class. The inflation that was common during wars due to the stagnation of trade, which was important for Innsbruck, worsened the lives of the subjects. In 1622, a bad harvest due to bad weather exacerbated the situation, which was already strained by the interest burden on the state budget caused by old debts. His insistence on enforcing modern Roman law across the board as opposed to traditional customary law did not win him any favour with many of his subjects.

All this did not stop Leopold and Claudia from holding court in a splendid absolutist manner. Innsbruck was extensively remodelled in Baroque style during Leopold's reign. Parties were held at court in the presence of the European aristocracy. Shows such as lion fights with the exotic animals from the prince's own stock, which Ferdinand II had established in the Court Garden, theatre and concerts served to entertain court society.

The morals and customs of the rugged Alpine people were to improve. It was a balancing act between festivities at court and the ban on carnival celebrations for normal citizens. The wrath of God, which after all had brought plague and war, was to be kept away as far as possible through virtuous behaviour. Swearing, shouting and the use of firearms in the streets were banned. The pious court took strict action against pimping, prostitution, adultery and moral decay. Jews also had hard times under Leopold and Claudia. The hatred of the always unloved Hebrew gave rise to one of the most unsavoury traditions of Tyrolean piety. In 1642, Dr Hippolyt Guarinoni, a monastery doctor of Italian origin from Hall and founder of the Karlskirche church in Volders, wrote the legend of the Martyr's child Anderle von Rinn. Inspired by Simon of Trento, who was allegedly murdered by Jews in his home town in 1475, Guarinoni wrote the Anderl song in verse. In Rinn near Innsbruck, an anti-Semitic Anderl cult developed around the remains of Andreas Oxner, who was allegedly murdered by Jews in 1462 - the year had appeared to the doctor in a dream - and was only banned by the Bishop of Innsbruck in 1989.

Innsbruck was not only cleaned morally, but also actually. Waste, which was a particular problem when there was no rain and no water flowing through the sewer system, was regularly cleaned up by princely decree. Farm animals were no longer allowed to roam freely within the city walls. The wave of plague a few years earlier was still fresh in the memory. Bad odours and miasmas were to be kept away at all costs.

After the early death of Leopold, Claudia ruled the country in place of her underage son with the help of her court chancellor Wilhelm Biener (1590 - 1651) with modern, confessionally motivated, early absolutist policies and a strict hand. She was able to rely on a well-functioning administration. The young widow surrounded herself with Italians and Italian-speaking Tyroleans, who brought fresh ideas into the country, but at the same time also toughness in the fight against the Lutheranism showed. In order to avoid fires, in 1636, the Lion house and the Ansitz Ruhelust Ferdinand II, stables and other wooden buildings within the city walls had to be demolished. Silkworm breeding in Trentino and the first tentative plans for a Tyrolean university flourished under Claudia's reign. Chancellor Biener centralised parts of the administration. Above all, the fragmented legal system within the Tyrolean territories was to be replaced by a universal code. To achieve this, the often arbitrary actions of the local petty nobility had to be further disempowered in favour of the sovereign.

This system was not only intended to finance the expensive court, but also the defence of the country. It was not only Protestant troops from southern Germany that threatened the Habsburg possessions. France, actually a Catholic power, also wanted to hold the lands of the Casa de Austria in Spain, Italy and the Vorlanden, today's Benelux countries, harmless. Innsbruck became one of the centres of the Habsburg war council. On the edge of the front in the German lands and centred between Vienna and Tuscany, the city was perfect for Austrians, Spaniards and Italians to meet. The Swedes, notorious for their brutality, threatened Tyrol directly, but were prevented from invading. The castle and ramparts that protected Tyrol were built by unwanted inhabitants of the country, beggars, gypsies and deserted soldiers using forced labour. Defences were built near Scharnitz on today's German border and named after the provincial princess Porta Claudia called.

When Claudia de Medici died in 1648, there was an uprising of the estates against the central government, as there was in England under Cromwell at almost the same time. Claudia, who had never learnt the local German language and was still unfamiliar with local customs even after more than 20 years, had never been particularly popular with the population. However, there was no question of deposing her. The cup of hemlock was passed on to her chancellor. The uncomfortable Biener was recognised by Claudia's successor, Archduke Ferdinand Karl, and the estates as a Persona non grata was imprisoned and, like Charles I, beheaded two years after a show trial in 1651.

A touch of Florence and Medici still characterises Innsbruck today: both the Jesuit church, where Claudia and Leopold found their final resting place, and the Mariahilf parish church still bear the coat of arms of their family with the red balls and lilies. The Old Town Hall in the old town centre is also known as Claudiana known. Remains of the Porta Claudia near Scharnitz still stand today. The theatre in Innsbruck is particularly associated with Leopold's name. The Leopold Fountain in front of the House of Music commemorates him. Those who dare to climb the striking Serles mountain start the hike at the Maria Waldrast monastery, which Leopold devotedly founded in 1621 as a theatre. marvellous picture of our dear lady at the Waldrast to the Servite Order and had Claudia extended. A street name in Saggen was dedicated to Chancellor Wilhelm Biener.

Innsbruck and the House of Habsburg

Today, Innsbruck's city centre is characterised by buildings and monuments that commemorate the Habsburg family. For many centuries, the Habsburgs were a European ruling dynasty whose sphere of influence included a wide variety of territories. At the zenith of their power, they were the rulers of a "Reich, in dem die Sonne nie untergeht". Through wars and skilful marriage and power politics, they sat at the levers of power between South America and the Ukraine in various eras. Innsbruck was repeatedly the centre of power for this dynasty. The relationship was particularly intense between the 15th and 17th centuries. Due to its strategically favourable location between the Italian cities and German centres such as Augsburg and Regensburg, Innsbruck was given a special place in the empire at the latest after its elevation to a royal seat under Emperor Maximilian.

Tyrol was a province and, as a conservative region, usually favoured the dynasty. Even after its time as a royal seat, the birth of new children of the ruling family was celebrated with parades and processions, deaths were mourned in memorial masses and archdukes, kings and emperors were immortalised in public spaces with statues and pictures. The Habsburgs also valued the loyalty of their Alpine subjects to the Nibelung. In the 19th century, the Jesuit Hartmann Grisar wrote the following about the celebrations to mark the birth of Archduke Leopold in 1716:

„But what an imposing sight it was when, as night fell, the Abbot of Wilten held the final religious function in front of St Anne's Column, which had been consecrated by the blood of the country, surrounded by rows of students and the packed crowd; when, by the light of thousands of burning lights and torches, the whole town, together with the studying youth, the hope of the country, implored heaven for a blessing for the Emperor's newborn first son.“

Its inaccessible location made it the perfect refuge in troubled and crisis-ridden times. Charles V (1500 - 1558) fled during a conflict with the Protestant Schmalkaldischen Bund to Innsbruck for some time. Ferdinand I (1793 - 1875) allowed his family to stay in Innsbruck, far away from the Ottoman threat in eastern Austria. Shortly before his coronation in the turbulent summer of the 1848 revolution, Franz Josef I enjoyed the seclusion of Innsbruck together with his brother Maximilian, who was later shot by insurgent nationalists as Emperor of Mexico. A plaque at the Alpengasthof Heiligwasser above Igls reminds us that the monarch spent the night here as part of his ascent of the Patscherkofel. Some of the Tyrolean sovereigns from the House of Habsburg had no special relationship with Tyrol, nor did they have any particular affection for this German land. Ferdinand I (1503 - 1564) was educated at the Spanish court. Maximilian's grandson Charles V had grown up in Burgundy. When he set foot on Spanish soil for the first time at the age of 17 to take over his mother Joan's inheritance of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, he did not speak a word of Spanish. When he was elected German Emperor in 1519, he did not speak a word of German.

Not all Habsburgs were happy to be „allowed“ to be in Innsbruck. Married princes and princesses such as Maximilian's second wife Bianca Maria Sforza or Ferdinand II's second wife Anna Caterina Gonzaga were stranded in the harsh, German-speaking mountains after the wedding without being asked. If you also imagine what a move and marriage from Italy to Tyrol to a foreign man meant for a teenager, you can imagine how difficult life was for the princesses. Until the 20th century, children of the aristocracy were primarily brought up to be politically married. There was no opposition to this. One might imagine courtly life to be ostentatious, but privacy was not provided for in all this luxury.

Innsbruck experienced its Habsburg heyday when the city was the main residence of the Tyrolean sovereigns. Ferdinand II, Maximilian III and Leopold V and their wives left their mark on the city during their reigns. When Sigismund Franz von Habsburg (1630 - 1665) died childless as the last sovereign prince, the title of residence city was also history and Tyrol was ruled by a governor. Tyrolean mining had lost its importance and did not require any special attention. Shortly afterwards, the Habsburgs lost their possessions in Western Europe along with Spain and Burgundy, which moved Innsbruck from the centre to the periphery of the empire. In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy of the 19th century, Innsbruck was the western outpost of a huge empire that stretched as far as today's Ukraine. Franz Josef I (1830 - 1916) ruled over a multi-ethnic empire between 1848 and 1916. However, his neo-absolutist concept of rule was out of date. Although Austria had had a parliament and a constitution since 1867, the emperor regarded this government as "his". Ministers were responsible to the emperor, who was above the government. In the second half of the 19th century, the ailing empire collapsed. On 28 October 1918, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was proclaimed, and on 29 October, Croats, Slovenes and Serbs left the monarchy. The last Emperor Charles abdicated on 11 November. On 12 November, "Deutschösterreich zur demokratischen Republik, in der alle Gewalt vom Volke ausgeht“. The chapter of the Habsburgs was over.

Despite all the national, economic and democratic problems that existed in the multi-ethnic states that were subject to the Habsburgs in various compositions and forms, the subsequent nation states were sometimes much less successful in reconciling the interests of minorities and cultural differences within their territories. Since the eastward enlargement of the EU, the Habsburg monarchy has been seen by some well-meaning historians as a pre-modern predecessor of the European Union. Together with the Catholic Church, the Habsburgs shaped the public sphere through architecture, art and culture. Goldenes DachlThe Hofburg, the Triumphal Gate, Ambras Castle, the Leopold Fountain and many other buildings still remind us of the presence of the most important ruling dynasty in European history in Innsbruck.

Andreas Hofer and the Tyrolean uprising of 1809

The Napoleonic Wars gave the province of Tyrol a national epic and, in Andreas Hofer, a hero whose splendour still shines today. However, if one subtracts the carefully constructed legend of the Tyrolean uprising against foreign rule, the period before and after 1809 was a dark chapter in Innsbruck's history, characterised by economic hardship, the devastation of war and several instances of looting. The Kingdom of Bavaria was allied with France during the Napoleonic Wars and was able to take over the province of Tyrol from the Habsburgs in several battles between 1796 and 1805. Innsbruck was no longer the capital of a crown land, but just one of many district capitals of the administrative unit Innkreis. Revenues from tolls and customs duties as well as from Hall salt left the country for the north. The British colonial blockade against Napoleon meant that Innsbruck's long-distance trade and transport industry, which had always flourished and brought prosperity, collapsed. Innsbruck's citizens had to accommodate Bavarian soldiers in their homes. The abolition of the Tyrolean provincial government, the gubernium and the Tyrolean parliament meant not only the loss of status, but also of jobs and financial resources. Inspired by the spirit of the Enlightenment, reason and the French Revolution, the new rulers set about overturning the traditional order. While the city suffered financially as a result of the war, as is always the case, the upheaval opened up new socio-political opportunities. War is the father of all things, The breath of fresh air was not inconvenient for many citizens. Modern laws such as the Alley cleaning order or compulsory smallpox immunisation were intended to promote cleanliness and health in the city. At the beginning of the 19th century, a considerable number of people were still dying from diseases caused by a lack of hygiene and contaminated drinking water. A new tax system was introduced and the powers of the nobility were further reduced. The Bavarian administration allowed associations, which had been banned in 1797, again. Liberal Innsbruckers also liked the fact that the church was pushed out of the education system. The Benedictine priest and later co-founder of the Innsbruck Music Society, Martin Goller, was appointed to Innsbruck to promote musical education.

Diese Reformen behagten einem großen Teil der Tiroler Bevölkerung nicht. Katholische Prozessionen und religiöse Feste fielen dem aufklärerischen Programm der neuen Landesherren zum Opfer. 1808 wurde vom bayerischen König für seinen gesamten Herrschaftsbereich das Gemeindeedikt eingeführt. Die Untertanen wurden darin verpflichtet öffentliche Gebäude, Brunnen, Wege, Brücken und andere Infrastruktur in Stand zu halten. Für die Tiroler Bauern, die seit Jahrhunderten von Fronarbeit größtenteils befreit waren, bedeutete das eine zusätzliche Belastung und war ein Affront gegen ihren Standesstozl. Der Funke, der das Pulverfass zur Explosion brachte, war die Aushebung junger Männer zum Dienst in der bayrisch-napoleonischen Armee, obwohl Tiroler seit dem LandlibellThe law of Emperor Maximilian stipulated that soldiers could only be called up for the defence of their own borders. On 10 April, there was a riot during a conscription in Axams near Innsbruck, which ultimately led to an uprising. For God, Emperor and Fatherland Tyrolean defence units came together to drive the small army and the Bavarian administrative officials out of Innsbruck. The riflemen were led by Andreas Hofer (1767 - 1810), an innkeeper, wine and horse trader from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley near Meran. He was supported not only by other Tyroleans such as Father Haspinger, Peter Mayr and Josef Speckbacher, but also by the Habsburg Archduke Johann in the background.

Once in Innsbruck, the marksmen not only plundered official facilities. As with the peasants' revolt under Michael Gaismair, their heroism was fuelled not only by adrenaline but also by alcohol. The wild mob was probably more damaging to the city than the Bavarian administrators had been since 1805, and the "liberators" rioted violently, particularly against middle-class ladies and the small Jewish population of Innsbruck.

In July 1809, Bavaria and the French took control of Innsbruck following the agreement with the Habsburgs. Peace of Znojmo, which many still regard as a Viennese betrayal of the province of Tyrol. What followed was what is known as Tyrolean survey under Andreas Hofer, who had meanwhile assumed supreme command of the Tyrolean defence forces, was to go down in the history books. The Tyrolean insurgents were able to carry victory from the battlefield a total of three times. The 3rd battle in August 1809 on Mount Isel is particularly well known. "Innsbruck sees and hears what it has never heard or seen before: a battle of 40,000 combatants...“ For a short time, Andreas Hofer was Tyrol's commander-in-chief in the absence of regular facts, also for civil affairs. Innsbruck's financial plight did not change. Instead of the Bavarian and French soldiers, the townspeople now had to house and feed their compatriots from the peasant regiment and pay taxes to the new provincial government. The city's liberal and wealthy elites in particular were not happy with the new city rulers. The decrees issued by him as provincial commander were more reminiscent of a theocracy than a 19th century body of laws. Women were only allowed to go out on the streets wearing chaste veils, dance events were banned and revealing monuments such as the one on the Leopoldsbrunnen nymphs on display were banned from public spaces. Educational agendas were to return to the clergy. Liberals and intellectuals were arrested, but the Praying the rosary zum Gebot. Am Ende gab es im Herbst 1809 in der vierten und letzten Schlacht am Berg Isel eine empfindliche Niederlage gegen die französische Übermacht. Die Regierung in Wien hatte die Tiroler Aufständischen vor allem als taktischen Prellbock im Krieg gegen Napoleon benutzt. Bereits zuvor hatte der Kaiser das Land Tirol offiziell im Friedensvertrag von Schönbrunn wieder abtreten müssen. Innsbruck war zwischen 1810 und 1814 wieder unter bayrischer Verwaltung. Auch die Bevölkerung war nur noch mäßig motiviert, Krieg zu führen. Wilten wurde von den Kampfhandlungen stark in Mitleidenschaft gezogen. Das Dorf schrumpfte von über 1000 Einwohnern auf knapp 700. Hofer selbst war zu dieser Zeit bereits ein von der Belastung dem Alkohol gezeichneter Mann. Er wurde gefangengenommen und am 20. Januar 1810 in Mantua hingerichtet. Zu allem Überfluss wurde das Land geteilt. Das Etschtal und das Trentino wurden Teil des von Napoleon aus dem Boden gestampften Königreich Italien, das Pustertal wurde den französisch kontrollierten Illyrian provinces connected.

Der „Fight for freedom" symbolises the Tyrolean self-image to this day. For a long time, Andreas Hofer, the innkeeper from the South Tyrolean Passeier Valley, was regarded as an undisputed hero and the prototype of the Tyrolean who was brave, loyal to his fatherland and steadfast. The underdog who fought back against foreign superiority and unholy customs. In fact, Hofer was probably a charismatic leader, but politically untalented and conservative-clerical, simple-minded. His tactics at the 3rd Battle of Mount Isel "Do not abandon them“ (Ann.: Ihr dürft sie nur nicht heraufkommen lassen) fasst sein Wesen wohl ganz gut zusammen. In konservativen Kreisen Tirols wie den Schützen wird Hofer unkritisch und kultisch verehrt. Das Tiroler Schützenwesen ist gelebtes Brauchtum, das sich zwar modernisiert hat, in vielen dunklen Winkeln aber noch reaktionär ausgerichtet ist. Wiltener, Amraser, Pradler und Höttinger Schützen marschieren immer noch einträchtig neben Klerus, Trachtenvereinen und Marschmusikkapellen bei kirchlichen Prozessionen und schießen in die Luft, um alles Übel von Tirol und der katholischen Kirche fernzuhalten. Über die Stadt verteilt erinnern viele Denkmäler an das Jahr 1809. Die zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts erfuhr eine Heroisierung der Kämpfer, die als deutsches Bollwerk gegen fremde Völkerschaften charakterisiert wurden. Der Berg Isel wurde der Stadt für die Verehrung der Freiheitskämpfer vom Stift Wilten, der katholischen Instanz Innsbrucks, zur Verfügung gestellt. Andreas Hofer und seinen Mitstreitern Josef Speckbacher, Peter Mayer, Pater Haspinger und Kajetan Sweth wurden im Stadtteil Wilten, das in der Zeit des großdeutsch-liberal dominierten Gemeinderats 1904 zu Innsbruck kam und lange unter der Verwaltung des Stiftes gestanden hatte, Straßennamen gewidmet. Das kurze Rote Gassl im alten Kern von Wilten erinnert an die Tiroler Schützen, die, in ihnen wohl fälschlich nachgesagten roten Uniformen, dem siegreichen Feldherrn Hofer nach dem Sieg in der zweiten Berg Isel Schlacht an dieser Stelle in Massen gehuldigt haben sollen. In Tirol wird Andreas Hofer bis heute gerne für alle möglichen Initiativen und Pläne vor den Karren gespannt. Vor allem im Nationalismus des 19. Jahrhunderts berief man sich immer wieder auf den verklärten Helden Andreas Hofer. Hofer wurde über Gemälde, Flugblätter und Schauspiele zur Ikone stilisiert. Aber auch heute noch kann man das Konterfei des Oberschützen sehen, wenn sich Tiroler gegen unliebsame Maßnahmen der Bundesregierung, den Transitbestimmungen der EU oder der FC Wacker gegen auswärtige Fußballvereine zur Wehr setzen. Das Motto lautet dann „Man, it's time!“. Die Legende vom wehrfähigen Tiroler Bauern, der unter Tags das Feld bestellt und sich abends am Schießstand zum Scharfschützen und Verteidiger der Heimat ausbilden lässt, wird immer wieder gerne aus der Schublade geholt zur Stärkung der „echten“ Tiroler Identität. Die Feiern zum Todestag Andreas Hofers am 20. Februar locken bis heute regelmäßig Menschenmassen aus allen Landesteilen Tirols in die Stadt. Erst in den letzten Jahrzehnten setzte eine kritische Betrachtung des erzkonservativen und mit seiner Aufgabe als Tiroler Landeskommandanten wohl überforderten Schützenhauptmanns ein, der angestachelt von Teilen der Habsburger und der katholischen Kirche nicht nur Franzosen und Bayern, sondern auch das liberale Gedankengut der Aufklärung vehement aus Tirol fernhalten wollte.

Baroque: art movement and art of living

Anyone travelling in Austria will be familiar with the domes and onion domes of churches in villages and towns. This form of church tower originated during the Counter-Reformation and is a typical feature of the Baroque architectural style. They are also predominant in Innsbruck's cityscape. Innsbruck's most famous places of worship, such as the cathedral, St John's Church and the Jesuit Church, are in the Baroque style. Places of worship were meant to be magnificent and splendid, a symbol of the victory of true faith. Religiousness was reflected in art and culture: grand drama, pathos, suffering, splendour and glory combined to create the Baroque style, which had a lasting impact on the entire Catholic-oriented sphere of influence of the Habsburgs and their allies between Spain and Hungary.

The cityscape of Innsbruck changed enormously. The Gumpps and Johann Georg Fischer as master builders as well as Franz Altmutter's paintings have had a lasting impact on Innsbruck to this day. The Old Country House in the historic city centre, the New Country House in Maria-Theresien-Straße, the countless palazzi, paintings, figures - the Baroque was the style-defining element of the House of Habsburg in the 17th and 18th centuries and became an integral part of everyday life. The bourgeoisie did not want to be inferior to the nobles and princes and had their private houses built in the Baroque style. Pictures of saints, depictions of the Mother of God and the heart of Jesus adorned farmhouses.

Baroque was not just an architectural style, it was an attitude to life that began after the end of the Thirty Years' War. The Turkish threat from the east, which culminated in the two sieges of Vienna, determined the foreign policy of the empire, while the Reformation dominated domestic politics. Baroque culture was a central element of Catholicism and its political representation in public, the counter-model to Calvin's and Luther's brittle and austere approach to life. Holidays with a Christian background were introduced to brighten up people's everyday lives. Architecture, music and painting were rich, opulent and lavish. In theatres such as the Comedihaus dramas with a religious background were performed in Innsbruck. Stations of the cross with chapels and depictions of the crucified Jesus dotted the landscape. Popular piety in the form of pilgrimages and the veneration of the Virgin Mary and saints found its way into everyday church life. Multiple crises characterised people's everyday lives. In addition to war and famine, the plague broke out particularly frequently in the 17th century. The Baroque piety was also used to educate the subjects. Even though the sale of indulgences was no longer a common practice in the Catholic Church after the 16th century, there was still a lively concept of heaven and hell. Through a virtuous life, i.e. a life in accordance with Catholic values and good behaviour as a subject towards the divine order, one could come a big step closer to paradise. The so-called Christian edification literature was popular among the population after the school reformation of the 18th century and showed how life should be lived. The suffering of the crucified Christ for humanity was seen as a symbol of the hardship of the subjects on earth within the feudal system. People used votive images to ask for help in difficult times or to thank the Mother of God for dangers and illnesses they had overcome.

The historian Ernst Hanisch described the Baroque and the influence it had on the Austrian way of life as follows:

„Österreich entstand in seiner modernen Form als Kreuzzugsimperialismus gegen die Türken und im Inneren gegen die Reformatoren. Das brachte Bürokratie und Militär, im Äußeren aber Multiethnien. Staat und Kirche probierten den intimen Lebensbereich der Bürger zu kontrollieren. Jeder musste sich durch den Beichtstuhl reformieren, die Sexualität wurde eingeschränkt, die normengerechte Sexualität wurden erzwungen. Menschen wurden systematisch zum Heucheln angeleitet.“

The rituals and submissive behaviour towards the authorities left their mark on everyday culture, which still distinguishes Catholic countries such as Austria and Italy from Protestant regions such as Germany, England or Scandinavia. The Austrians' passion for academic titles has its origins in the Baroque hierarchies. The expression Baroque prince describes a particularly patriarchal and patronising politician who knows how to charm his audience with grand gestures. While political objectivity is valued in Germany, the style of Austrian politicians is theatrical, in keeping with the Austrian bon mot of "Schaumamal".