Servitenkirche

Maria-Theresienstrasse 42

Worth knowing

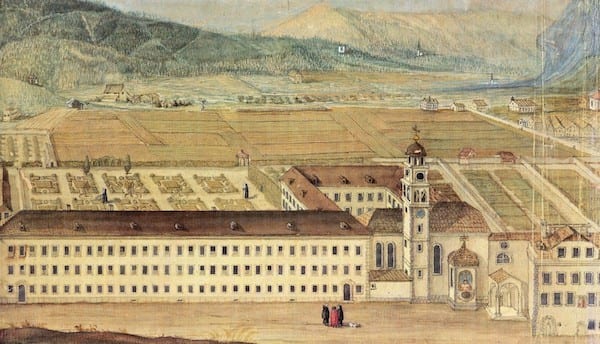

Die Geschichte der Servitenkirche ist bewegter als man dem unscheinbaren Gotteshaus ansieht. Anna Catarina Gonzaga (1566 – 1621), die zweite Frau Ferdinand II., gründete 1613 in Innsbruck mit der Servitenkirche die erste Niederlassung der Neuzeit des „Ordo Servorum Mariae" (Order of the Servants of Mary) north of the Alps. The mosaic in the entrance vault shows the coat of arms of the Duchy of Mantua with the 4 black eagles and the red lion together with the coat of arms of the Archduchy of Austria. It symbolises the unity of Ferdinand and Anna Catarina Gonzaga and their dynasties. Although the city-states of Italy were past their prime, they still had the means to intermarry with the highest circles of the European aristocracy. The northern Italian principalities and the Habsburgs were the Catholic bulwark of Europe at this time of schism. The ceiling fresco in the interior of the church impressively depicts the roots of the church's founder.

The establishment of this strict order was of great concern to the pious sovereigns with Italian roots. As a mendicant order, the Servites dedicated themselves to caring for the poor in their early days. During the Reformation, the Servite order, which originated in Tuscany, was completely dissolved in German-speaking countries and was only able to spread again from Innsbruck in the 17th century. Today, the Servites are mainly involved in development aid.

The first building burnt down in a fire in 1620. The plan to be buried in the church, which they had donated themselves, had to be postponed for the time being. Johann Martin and Georg Anton Gumpp planned the new building in 1626 in the Baroque style. Anna Caterina Gonzaga had already died by this time. Instead of being buried in the Servite church as planned, she was buried in the Servite convent until completion, and later in the Jesuit church. It was not until 1693 that she was reinterred in the church together with her daughter.

In the 20th century, the Servite Church was once again on the brink of collapse. On 3 November 1938, the National Socialists dissolved the Servite Order as the first monastery in Innsbruck "zum Schutze des Volkes" on. In Catholic Tyrol in particular, actions against the church had to be planned and communicated with great care. Often the most hair-raising stories were put out into the world. In the Austrian edition of the "Völkischen Beobachter“ vom 4. November 1938 ist als Grund dafür zu lesen:

„Staatspolizeiliche Untersuchungen im Servitenkloster in Innsbruck ergaben, dass in diesem Kloster derart sittenwidrige Zustände herrschen, dass es unmöglich ist, sie in der Öffentlichkeit zu unterbreiten. Es handelt sich bei dem genannten Kloster um eine Lasterhöhle erster Ordnung, hinter deren Treiben das staatsfeindliche Verhalten, das durch aufgefundene Schriften festgestellt wurde, weit in den Hintergrund tritt.“

Am 15. Dezember 1943 wurde die Servitenkirche bei einem Bombenangriff auf Innsbruck zerstört. Das markante Gemälde an der Außenseite und das Deckenfresko wurden nach 1945 beim Wiederaufbau von Hans Andre, der nach dem Krieg auch die ramponierte Spitalskirche (33) auf Vordermann brachte, neu geschaffen.

Anna Caterina Gonzaga - die fromme Landesfürstin

Innsbruckers like to see themselves as a kind of northern outpost of Italy, a mixture of Italian art de vivre and German precision. In addition to the preference for wine and beer in equal measure, the Tyrolean sovereigns' fondness for the daughters of the Italian high aristocracy and their influence on the city could also be a reason for this. Anna Caterina Gonzaga (1566 - 1621), known as "Principessa"Born in the city of Mantua at the age of 16, he was forced to marry Ferdinand II, the prince of Tyrol, who was known as a bon vivant. While his first wife Philippine Welser was still alive but already ill, he had asked for her hand in marriage. At the time, Mantua was one of the richest royal courts in Europe and a centre of the Renaissance. Ferdinand was already 53 at the time of the wedding and was also Anna Caterina Gonzaga's uncle thanks to unfavourable entanglements in the wedding politics of previous decades. In order for the wedding to take place, the Pope had to issue a special licence. The marriage was necessary because Ferdinand was unable to claim an heir to the throne from his first marriage. Ferdinand II also had "only" three daughters with Anna Catarina. For the House of Habsburg, the marriage meant a considerable dowry, which came to Tyrol from Mantua. In return, Anna Caterina Gonzaga's father was able to boast the title Hoheit which Emperor Rudolf II, like Ferdinand a Habsburg, bestowed on him.

The pious Mantovan woman took refuge in her faith in Tyrol. After the Jesuits under Ferdinand I and the Franciscans, the Capuchins settled in Innsbruck in 1593 under the care of Anna Caterina Gonzaga. In the Silbergasse at the eastern end of the Hofgarten, a Regelhaus, um es der Landesfürstin zu ermöglichen ihrem Glauben in aller Stille nachgehen zu können, ohne sich in aller Strenge dem Klosterleben unterwerfen zu müssen. Nach dem Tod Ferdinands im Jahre 1595 gründete die nunmehrige Landesfürstin von Tirol und tiefgläubige Frau das Servitenkloster in Innsbruck. Die Serviten waren im Volk sehr beliebt, hielten sie doch Armenspeisungen ab. Großzügige Stiftungen an die Kirche waren nicht ungewöhnlich. Neben einem gottgefälligen Leben waren Geschenke an die Kirche und Gebete nach dem Ableben eine Möglichkeit, das Seelenheil zu erlangen. Mitglieder des Hauses Habsburg im Speziellen hatten diese Sitte in ihrer Frömmigkeit seit jeher betrieben und ließen auch in der Neuzeit nicht davon ab. Anna Caterina Gonzaga selbst trat mit ihrer Tochter Maria in das Regelhaus ein, ein offenes Damenkloster mit etwas legereren Regeln, wo sie bis an ihr Lebensende ihrem Glauben nachging. Ihre Grablege fand sie zunächst in der Gruft des Servitinnenklosters gemeinsam mit ihrer Tochter. 1693 wurden die sterblichen Überreste der beiden Frauen in die Jesuitenkirche überstellt. Erst im Jahr 1906 fanden sie ihre letzte Ruhestätte im Servitenkloster in der Maria-Theresien-Straße.

The Red Bishop and Innsbruck's moral decay

In the 1950s, Innsbruck began to recover from the crisis and war years of the first half of the 20th century. On 15 May 1955, Federal Chancellor Leopold Figl declared with the famous words "Austria is free" and the signing of the State Treaty officially marked the political turning point. In many households, the "political turnaround" became established in the years known as Economic miracle moderate prosperity in the years that went down in history. This period not only brought material change, but also social change. People's desires became more outlandish as prosperity increased and the lifestyle conveyed in advertising and the media became more sophisticated. The phenomenon of a new youth culture began to spread gently amidst the grey society of post-war Austria. The terms Teenager and latchkey child entered the Austrian language in the 1950s.

Films brought the big world to Innsbruck. Cinema screenings and cinemas already existed in Innsbruck at the turn of the century, but in the post-war period the programme was adapted to a young audience for the first time. Hardly anyone had a television set in their living room and the programme was meagre. The Chamber light theatre in Wilhelm-Greilstraße, the Laurin cinema in the Gumppstraße, the Central cinema in Maria-Theresienstraße, which Löwen-Lichtspiele in the Höttingergasse and the Leocinema of the Catholic Workers' Association in Anichstraße courted the public's favour with scandalous films.

1956 saw the publication of the magazine BRAVO. For the first time, there was a medium that was orientated towards the interests of young people. The first issue featured Marylin Monroe, including the question: Did Marylin's curves get married too? The big stars of the early years were James Dean and Peter Kraus, before the Beatles took over in the 1960s. After the Summer of Love Dr Sommer explained about love and sex. The first photo love story with bare breasts did not follow until 1982.

Bars, discos, nightclubs, pubs and event venues gradually opened in Innsbruck. Events such as the 5 o'clock tea dance at the Sporthotel Igls attracted young people looking for a mate. Establishments such as the Falconry cellar in the Gilmstraße, the Uptown Jazzsalon in Hötting, the Clima Club in Saggen, the Scotch Club in the Angerzellgasse and the Tangent in Bruneckerstraße had nothing in common with the traditional Tyrolean beer and wine bar. The performances by the Rolling Stones and Deep Purple in the Olympic Hall in 1973 were the high point of Innsbruck's spring awakening for the time being. Innsbruck may not have become London or San Francisco, but it had at least breathed a breath of rock'n'roll.

However, the vast majority of the social life of the city's young people did not take place in disreputable dives, but in the orderly channels of Catholic youth organisations. What is still anchored in cultural memory today as the '68 movement took place in the Holy Land did not take place. Neither workers nor students took to the barricades. Beethoven's wisdom that "As long as the Austrians still have brown beer and sausages, they won't revolt," was true.

Nevertheless, society was quietly and secretly changing. A look at the annual charts gives an indication of this. In 1964, it was still Chaplain Alfred Flury and Freddy with "Leave the little things“ and „Give me your word" and the Beatles with their German version of "Come, give me your hand", which dominated the Top 10, musical tastes changed in the years leading up to the 1970s. Peter Alexander and Mireille Mathieu were still to be found in the charts. From 1967, however, it was international bands with foreign-language lyrics such as The Rolling Stones, Tom Jones, The Monkees, Scott McKenzie, Adriano Celentano and Simon and Garfunkel, some of whom had socially critical lyrics, that occupied the top positions in large numbers.

The spearhead of the conservative counter-revolution was the Innsbruck bishop Paulus Rusch. Cigarettes, alcohol, overly permissive fashion, holidays abroad, working women, nightclubs, premarital sex, the 40-hour week, Sunday sporting events, dance evenings, mixed sex in school and leisure - all of these were strictly forbidden to the strict churchman and follower of the Sacred Heart cult.

Peter Paul Rusch was born in Munich in 1903 and grew up in Vorarlberg as the youngest of three children in a middle-class household. Both parents and his older sister died of tuberculosis before he reached adulthood. At the young age of 17, Rusch had to fend for himself in the meagre post-war period. Inflation had eaten up his father's inheritance, which could have financed his studies, in no time at all. Rusch worked for six years at the Bank for Tyrol and Vorarlbergin order to finance his theological studies. He entered the Collegium Canisianum in 1927 and was ordained a priest of the Jesuit order six years later. His stellar career took the intelligent young man first to Lech and Hohenems as chaplain and then back to Innsbruck as head of the seminary. Here he became titular bishop of Lykopolis in 1938, Innsbruck only becoming its own diocese in 1964, and Apostolic Administrator for Tyrol and Vorarlberg. As the youngest bishop in Europe, he had to survive the harassment of the church by the National Socialist rulers. Although his critical attitude towards National Socialism was well known, Rusch himself was never imprisoned. Those in power were too afraid of turning the popular young bishop into a martyr.

After the war, the socially and politically committed bishop was at the forefront of reconstruction efforts. He wanted the church to have more influence on people's everyday lives again. His father had worked his way up from carpenter to architect and probably gave him a soft spot for the building industry. He also had his own experience at BTV. Thanks to his training as a banker, Rusch recognised the opportunities for the church to get involved and make a name for itself as a helper in times of need. It was not only the churches that had been damaged in the war that were rebuilt. The Catholic Youth under Rusch's leadership, was involved free of charge in the construction of the Heiligjahrsiedlung in the Höttinger Au. The diocese bought a building plot from the Ursuline order for this purpose. The loans for the settlers were advanced interest-free by the church. Decades later, his rustic approach to the housing issue would earn him the title of "Red Bishop" to the new home. In the modest little houses with self-catering gardens, in line with the ideas of the dogmatic and frugal "working-class bishop", 41 families, preferably with many children, found a new home.

By alleviating the housing shortage, the greatest threats in the Cold WarCommunism and socialism, from his community. The atheism prescribed by communism and the consumer-orientated capitalism that had swept into Western Europe from the USA after the war were anathema to him. In 1953, Rusch's book "Young worker, where to?". What sounds like revolutionary, left-wing reading from the Kremlin showed the principles of Christian social teaching, which castigated both capitalism and socialism. Families should live modestly in order to live in Christian harmony with the moderate financial means of a single father. Entrepreneurs, employees and workers were to form a peaceful unity. Co-operation instead of class warfare, the basis of today's social partnership. To each his own place in a Christian sense, a kind of modern feudal system that was already planned for use in Dollfuß's corporative state. He shared his political views with Governor Eduard Wallnöfer and Mayor Alois Lugger, who, together with the bishop, organised the Holy Trinity of conservative Tyrol at the time of the economic miracle. Rusch combined this with a latent Catholic anti-Semitism that was still widespread in Tyrol after 1945 and which, thanks to aberrations such as the veneration of the Anderle von Rinn has long been a tradition.

Education and training were of particular concern to the pugnacious Jesuit. Despite a speech impediment, Rusch was a charismatic character who was extremely popular with his young colleagues and young people. In 1936, he was elected regional field master of the scouts in Vorarlberg. In his opinion, only a sound education under the wing of the church according to the Christian model could save the salvation of young people. In order to give young people a perspective and steer them in an orderly direction with a home and family, the Youth building society savings strengthened. In the parishes, kindergartens, youth centres and educational institutions such as the House of encounter am Rennweg in order to have education in the hands of the church from the very beginning.

In the 1960s and 70s there were two church youth movements in Innsbruck. The education of the elites in the spirit of the Jesuit order was provided in Innsbruck since 1578 by the Marian Congregation. This youth organisation, still known today as the MK, took care of secondary school pupils. The MK had a strict hierarchical structure in order to give the young Soldaten Christi obedience from the very beginning. Father Sigmund Kripp took over the MK in 1959. Under his leadership, the young people built projects such as the Mittergrathütte including its own material cable car in Kühtai and the MK youth centre Kennedyhaus in Sillgasse with financial support from the church, state and parents and with a great deal of personal effort. Chancellor Klaus and members of the American embassy were present at the laying of the foundation stone for this youth centre, which was to become the largest of its kind in Europe with almost 1,500 members, as the building was dedicated to the first Catholic president of the USA, who had only recently been assassinated.

The other church youth organisation in Innsbruck was Z6. The city's youth chaplain, Chaplain Meinrad Schumacher, took care of the youth organisation as part of the Action 4-5-6 to all young people who are in the MK or the Catholic Student Union had no place. Working-class children and apprentices met in various youth centres such as Pradl or Reichenau before the new centre, also built by the members themselves, was opened at Zollerstraße 6 in 1971. Josef Windischer took over the management of the centre. The Z6 already had more to do with what Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda were doing on the big screen on their motorbikes in Easy Rider was shown. Things were rougher here than in the MK. Rocker gangs like the Santanas, petty criminals and drug addicts also spent their free time in Z6. While Schumacher reeled off his programme upstairs with the "good" youngsters, Windischer populated the basement with the Outsiders to help the lost sheep as much as possible.

At the end of the 1960s, both the MK and the Z6 decided to open up to non-members. Girls' and boys' groups were partially merged and non-members were also admitted. Although the two youth centres had different target groups, the concept was the same. Theological knowledge and Christian morals were taught in a playful, age-appropriate environment. Sections such as chess, football, hockey, basketball, music, cinema films and a party room catered to the young people's needs for games, sport and their first sexual experiences. The youth centres offered a space in which young people of both sexes could meet. However, the MK in particular remained an institution that had nothing to do with the wild life of the '68ers, as it is often portrayed in films. For example, dance courses did not take place during Advent, carnival or on Saturdays, and were forbidden for under-17s.

Nevertheless, the youth centres went too far for Bishop Rusch. The critical articles in the MK newspaper We discuss found less and less favour. After years of disputes between the bishop and the youth centre, it came to a showdown in 1973. When Father Kripp published his book Farewell to tomorrow in which he reported on his pedagogical concept and the work in the MK, there were non-public proceedings within the diocese and the Jesuit order against the director of the youth centre. Despite massive protests from parents and members, Kripp was removed. Neither the intervention within the church by the eminent theologian Karl Rahner, nor a petition launched by the artist Paul Flora, nor regional and national outrage in the press could save the overly liberal priest from the wrath of Rusch, who even secured the papal blessing from Rome for his removal from office. In July 1974, the Z6 was also temporarily closed. Rusch had the keys to the youth centre exchanged without further ado, a method he had also used with the Catholic Student Union when it got too close to a left-wing action group.

It was his adherence to conservative values and his stubbornness that damaged Rusch's reputation in the last 20 years of his life. When he was consecrated as the first bishop of the newly founded diocese of Innsbruck in 1964, times were changing. The progressive with practical life experience of the past was overtaken by the modern life of a new generation and its needs. The bishop's constant criticism of the lifestyle of his flock and his stubborn adherence to his overly conservative values, coupled with sometimes bizarre statements, turned the co-founder of development aid into a bishop. Brother in needthe young, hands-on bishop of the reconstruction, from the late 1960s onwards as a reason for leaving the church. His concept of repentance and penance took on bizarre forms. He demanded guilt and atonement from the Tyroleans for their misdemeanours during the Nazi era, but at the same time described the denazification laws as too far-reaching and strict. In response to the new sexual practices and abortion laws under Chancellor Kreisky, he said that girls and young women who have premature sexual intercourse are up to twelve times more likely to develop cancer of the mother's organs. Rusch described Hamburg as a cesspool of sin and he suspected that the simple minds of the Tyrolean population were not up to phenomena such as tourism and nightclubs and were tempted to immoral behaviour. He feared that technology and progress were making people too independent of God. He was strictly against the new custom of double income. People should be satisfied with a spiritual family home with a vegetable garden and not strive for more; women should concentrate on their traditional role as housewife and mother.

In 1973, after 35 years at the head of the church community in Tyrol and Innsbruck, Bishop Rusch was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck. He resigned from his office in 1981. In 1986, Innsbruck's first bishop was laid to rest in St Jakob's Cathedral. The Bishop Paul's Student Residence The church of St Peter Canisius in the Höttinger Au, which was built under him, commemorates him.

After its closure in 1974, the Z6 youth centre moved to Andreas-Hofer-Straße 11 before finding its current home in Dreiheiligenstraße, in the middle of the working-class district of the early modern period opposite the Pest Church. Jussuf Windischer remained in Innsbruck after working on social projects in Brazil. The father of four children continued to work with socially marginalised groups, was a lecturer at the Social Academy, prison chaplain and director of the Caritas Integration House in Innsbruck.

The MK also still exists today, even though the Kennedy House, which was converted into a Sigmund Kripp House was renamed, no longer exists. In 2005, Kripp was made an honorary citizen of the city of Innsbruck by his former sodalist and later deputy mayor, like Bishop Rusch before him.

Believe, Church and Power

The abundance of churches, chapels, crucifixes and murals in public spaces has a peculiar effect on many visitors to Innsbruck from other countries. Not only places of worship, but also many private homes are decorated with depictions of the Holy Family or biblical scenes. The Christian faith and its institutions have characterised everyday life throughout Europe for centuries. Innsbruck, as the residence city of the strictly Catholic Habsburgs and capital of the self-proclaimed Holy Land of Tyrol, was particularly favoured when it came to the decoration of ecclesiastical buildings. The dimensions of the churches alone are gigantic by the standards of the past. In the 16th century, the town with its population of just under 5,000 had several churches that outshone every other building in terms of splendour and size, including the palaces of the aristocracy. Wilten Monastery was a huge complex in the centre of a small farming village that was grouped around it. The spatial dimensions of the places of worship reflect their importance in the political and social structure.

For many Innsbruck residents, the church was not only a moral authority, but also a secular landlord. The Bishop of Brixen was formally on an equal footing with the sovereign. The peasants worked on the bishop's estates in the same way as they worked for a secular prince on his estates. This gave them tax and legal sovereignty over many people. The ecclesiastical landowners were not regarded as less strict, but even as particularly demanding towards their subjects. At the same time, it was also the clergy in Innsbruck who were largely responsible for social welfare, nursing, care for the poor and orphans, feeding and education. The influence of the church extended into the material world in much the same way as the state does today with its tax office, police, education system and labour office. What democracy, parliament and the market economy are to us today, the Bible and pastors were to the people of past centuries: a reality that maintained order. To believe that all churchmen were cynical men of power who exploited their uneducated subjects is not correct. The majority of both the clergy and the nobility were pious and godly, albeit in a way that is difficult to understand from today's perspective.

Unlike today, religion was by no means a private matter. Violations of religion and morals were tried in secular courts and severely penalised. The charge for misconduct was heresy, which encompassed a wide range of offences. Sodomy, i.e. any sexual act that did not serve procreation, sorcery, witchcraft, blasphemy - in short, any deviation from the right belief in God - could be punished with burning. Burning was intended to purify the condemned and destroy them and their sinful behaviour once and for all in order to eradicate evil from the community.

For a long time, the church regulated the everyday social fabric of people down to the smallest details of daily life. Church bells determined people's schedules. Their sound called people to work, to church services or signalled the death of a member of the congregation. People were able to distinguish between individual bell sounds and their meaning. Sundays and public holidays structured the time. Fasting days regulated the diet. Family life, sexuality and individual behaviour had to be guided by the morals laid down by the church. The salvation of the soul in the next life was more important to many people than happiness on earth, as this was in any case predetermined by the events of time and divine will. Purgatory, the last judgement and the torments of hell were a reality and also frightened and disciplined adults.

While Innsbruck's bourgeoisie had been at least gently kissed awake by the ideas of the Enlightenment after the Napoleonic Wars, the majority of people in the surrounding communities remained attached to the mixture of conservative Catholicism and superstitious popular piety.

Faith and the church still have a firm place in the everyday lives of Innsbruck residents, albeit often unnoticed. The resignations from the church in recent decades have put a dent in the official number of members and leisure events are better attended than Sunday masses. However, the Roman Catholic Church still has a lot of ground in and around Innsbruck, even outside the walls of the respective monasteries and educational centres. A number of schools in and around Innsbruck are also under the influence of conservative forces and the church. And anyone who always enjoys a public holiday, pecks one Easter egg after another or lights a candle on the Christmas tree does not have to be a Christian to act in the name of Jesus disguised as tradition.

Baroque: art movement and art of living

Anyone travelling in Austria will be familiar with the domes and onion domes of churches in villages and towns. This form of church tower originated during the Counter-Reformation and is a typical feature of the Baroque architectural style. They are also predominant in Innsbruck's cityscape. Innsbruck's most famous places of worship, such as the cathedral, St John's Church and the Jesuit Church, are in the Baroque style. Places of worship were meant to be magnificent and splendid, a symbol of the victory of true faith. Religiousness was reflected in art and culture: grand drama, pathos, suffering, splendour and glory combined to create the Baroque style, which had a lasting impact on the entire Catholic-oriented sphere of influence of the Habsburgs and their allies between Spain and Hungary.

The cityscape of Innsbruck changed enormously. The Gumpps and Johann Georg Fischer as master builders as well as Franz Altmutter's paintings have had a lasting impact on Innsbruck to this day. The Old Country House in the historic city centre, the New Country House in Maria-Theresien-Straße, the countless palazzi, paintings, figures - the Baroque was the style-defining element of the House of Habsburg in the 17th and 18th centuries and became an integral part of everyday life. The bourgeoisie did not want to be inferior to the nobles and princes and had their private houses built in the Baroque style. Pictures of saints, depictions of the Mother of God and the heart of Jesus adorned farmhouses.

Baroque was not just an architectural style, it was an attitude to life that began after the end of the Thirty Years' War. The Turkish threat from the east, which culminated in the two sieges of Vienna, determined the foreign policy of the empire, while the Reformation dominated domestic politics. Baroque culture was a central element of Catholicism and its political representation in public, the counter-model to Calvin's and Luther's brittle and austere approach to life. Holidays with a Christian background were introduced to brighten up people's everyday lives. Architecture, music and painting were rich, opulent and lavish. In theatres such as the Comedihaus dramas with a religious background were performed in Innsbruck. Stations of the cross with chapels and depictions of the crucified Jesus dotted the landscape. Popular piety in the form of pilgrimages and the veneration of the Virgin Mary and saints found its way into everyday church life.

The Baroque piety was also used to educate the subjects. Even though the sale of indulgences was no longer a common practice in the Catholic Church after the 16th century, there was still a lively concept of heaven and hell. Through a virtuous life, i.e. a life in accordance with Catholic values and good behaviour as a subject towards the divine order, one could come a big step closer to paradise. The so-called Christian edification literature was popular among the population after the school reformation of the 18th century and showed how life should be lived. The suffering of the crucified Christ for humanity was seen as a symbol of the hardship of the subjects on earth within the feudal system. People used votive images to ask for help in difficult times or to thank the Mother of God for dangers and illnesses they had overcome. Great examples of this can be found on the eastern façade of the basilica in Wilten.

The historian Ernst Hanisch described the Baroque and the influence it had on the Austrian way of life as follows:

„Österreich entstand in seiner modernen Form als Kreuzzugsimperialismus gegen die Türken und im Inneren gegen die Reformatoren. Das brachte Bürokratie und Militär, im Äußeren aber Multiethnien. Staat und Kirche probierten den intimen Lebensbereich der Bürger zu kontrollieren. Jeder musste sich durch den Beichtstuhl reformieren, die Sexualität wurde eingeschränkt, die normengerechte Sexualität wurden erzwungen. Menschen wurden systematisch zum Heucheln angeleitet.“

The rituals and submissive behaviour towards the authorities left their mark on everyday culture, which still distinguishes Catholic countries such as Austria and Italy from Protestant regions such as Germany, England or Scandinavia. The Austrians' passion for academic titles has its origins in the Baroque hierarchies. The expression Baroque prince describes a particularly patriarchal and patronising politician who knows how to charm his audience with grand gestures. While political objectivity is valued in Germany, the style of Austrian politicians is theatrical, in keeping with the Austrian bon mot of "Schaumamal".

The master builders Gumpp and the baroqueisation of Innsbruck

Die Werke der Familie Gumpp bestimmen bis heute sehr stark das Aussehen Innsbrucks. Vor allem die barocken Teile der Stadt sind auf die Hofbaumeister zurückzuführen. Der Begründer der Dynastie in Tirol, Christoph Gumpp (1600-1672) war eigentlich Tischler. Sein Talent allerdings hatte ihn für höhere Weihen auserkoren. Den Beruf des Architekten gab es zu dieser Zeit noch nicht. Michelangelo und Leonardo Da Vinci galten in ihrer Zeit als Handwerker, nicht als Künstler. Der Ruhm ihrer Kunstwerke allerdings hatte den Wert italienischer Baumeister innerhalb der Aristokratie immens nach oben getrieben. Wer auf sich hielt, beschäftigte jemand aus dem Süden am Hof. Christoph Gumpp, obwohl aus dem Schwabenland nach Innsbruck gekommen, trat nach seiner Mitarbeit an der Dreifaltigkeitskirche in die Fußstapfen der von Ferdinand II. hochgeschätzten Renaissance-Architekten aus Italien. Auf Geheiß Ferdinands Nachfolger Leopold V. reiste Gumpp nach Italien, um dort Theaterbauten zu studieren- Er sollte bei den kulturell den Ton angebenden Nachbarn südlich des Brenners sein Wissen für das geplante landesfürstliche Comedihaus aufzupolieren. Gumpps offizielle Tätigkeit als Hofbaumeister begann 1633 und er sollte diesen Titel an die nächsten beiden Generationen weitervererben. Über die folgenden Jahrzehnte sollte Innsbruck einer kompletten Renovierung unterzogen werden. Neue Zeiten bedurften eines neuen Designs, abseits des düsteren, von der Gotik geprägten Mittelalters. Die Gumpps traten nicht nur als Baumeister in Erscheinung. Sie waren Tischler, Maler, Kupferstecher und Architekten, was ihnen erlaubte, ähnlich der Bewegung der Tiroler Moderne rund um Franz Baumann und Clemens Holzmeister Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts, Projekte ganzheitlich umzusetzen. Johann Martin Gumpp der Ältere, Georg Anton Gumpp und Johann Martin Gumpp der Jüngere waren für viele der bis heute prägendsten Gebäude zuständig. So stammen die Wiltener Stiftskirche, die Mariahilfkirche, die Johanneskirche und die Spitalskirche von den Gumpps. Neben Kirchen und ihrer Arbeit als Hofbaumeister machten sie sich auch als Planer von Profanbauten einen Namen. Viele der Bürgerhäuser und Stadtpaläste Innsbrucks wie das Taxispalais oder das Alte Landhaus in der Maria-Theresien-Straße wurden von Ihnen entworfen. Das Meisterstück aber war das Comedihaus, das Christoph Gumpp für Leopold V. und Claudia de Medici im ehemaligen Ballhaus plante. Die überdimensionierten Maße des damals richtungsweisenden Theaters, das in Europa zu den ersten seiner Art überhaupt gehörte, erlaubte nicht nur die Aufführung von Theaterstücken, sondern auch Wasserspiele mit echten Schiffen und aufwändige Pferdeballettaufführungen. Das Comedihaus war ein Gesamtkunstwerk an und für sich, das in seiner damaligen Bedeutung wohl mit dem Festspielhaus in Bayreuth des 19. Jahrhunderts oder der Elbphilharmonie heute verglichen werden muss. Das ehemalige Wohnhaus der Familie Gumpp kann heute noch begutachtet werden, es beherbergt heute die Konditorei Munding, eines der traditionsreichsten Cafés der Stadt.

Air raids on Innsbruck

Like the course of the city's history, its appearance is also subject to constant change. The years around 1500 and between 1850 and 1900, when political, economic and social changes took place at a particularly rapid pace, produced particularly visible changes in the cityscape. However, the most drastic event with the greatest impact on the cityscape was probably the air raids on the city during the Second World War.

In addition to the food shortage, people suffered from what the National Socialists called the "Heimatfront" in the city were particularly affected by the Allied air raids. Innsbruck was an important supply station for supplies on the Italian front.

The first Allied air raid on the ill-prepared city took place on the night of 15-16 December 1943. 269 people fell victim to the bombs, 500 were injured and more than 1500 were left homeless. Over 300 buildings, mainly in Wilten and the city centre, were destroyed and damaged. On Monday 18 December, the following were found in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten, dem Vorgänger der Tiroler Tageszeitung, auf der Titelseite allerhand propagandistische Meldungen vom erfolgreichen und heroischen Abwehrkampf der Deutschen Wehrmacht an allen Fronten gegenüber dem Bündnis aus Anglo-Amerikanern und dem Russen, nicht aber vom Bombenangriff auf Innsbruck.

Bombenterror über Innsbruck

Innsbruck, 17. Dez. Der 16. Dezember wird in der Geschichte Innsbrucks als der Tag vermerkt bleiben, an dem der Luftterror der Anglo-Amerikaner die Gauhauptstadt mit der ganzen Schwere dieser gemeinen und brutalen Kampfweise, die man nicht mehr Kriegführung nennen kann, getroffen hat. In mehreren Wellen flogen feindliche Kampfverbände die Stadt an und richteten ihre Angriffe mit zahlreichen Spreng- und Brandbomben gegen die Wohngebiete. Schwerste Schäden an Wohngebäuden, an Krankenhäusern und anderen Gemeinschaftseinrichtungen waren das traurige, alle bisherigen Schäden übersteigende Ergebnis dieses verbrecherischen Überfalles, der über zahlreiche Familien unserer Stadt schwerste Leiden und empfindliche Belastung der Lebensführung, das bittere Los der Vernichtung liebgewordenen Besitzes, der Zerstörung von Heim und Herd und der Heimatlosigkeit gebracht hat. Grenzenloser Haß und das glühende Verlangen diese unmenschliche Untat mit schonungsloser Schärfe zu vergelten, sind die einzige Empfindung, die außer der Auseinandersetzung mit den eigenen und den Gemeinschaftssorgen alle Gemüter bewegt. Wir alle blicken voll Vertrauen auf unsere Soldaten und erwarten mit Zuversicht den Tag, an dem der Führer den Befehl geben wird, ihre geballte Kraft mit neuen Waffen gegen den Feind im Westen einzusetzen, der durch seinen Mord- und Brandterror gegen Wehrlose neuerdings bewiesen hat, daß er sich von den asiatischen Bestien im Osten durch nichts unterscheidet – es wäre denn durch größere Feigheit. Die Luftschutzeinrichtungen der Stadt haben sich ebenso bewährt, wie die Luftschutzdisziplin der Bevölkerung. Bis zur Stunde sind 26 Gefallene gemeldet, deren Zahl sich aller Voraussicht nach nicht wesentlich erhöhen dürfte. Die Hilfsmaßnahmen haben unter Führung der Partei und tatkräftigen Mitarbeit der Wehrmacht sofort und wirkungsvoll eingesetzt.

Diese durch Zensur und Gleichschaltung der Medien fantasievoll gestaltete Nachricht schaffte es gerade mal auf Seite 3. Prominenter wollte man die schlechte Vorbereitung der Stadt auf das absehbare Bombardement wohl nicht dem Volkskörper präsentieren. Ganz so groß wie 1938 nach dem Anschluss, als Hitler am 5. April von 100.000 Menschen in Innsbruck begeistert empfangen worden war, dürfte die Begeisterung für den Nationalsozialismus nicht mehr gewesen sein. Zu groß waren die Schäden an der Stadt und die persönlichen, tragischen Verluste in der Bevölkerung. Im Jänner 1944 begann man Luftschutzstollen und andere Schutzmaßnahmen zu errichten. Die Arbeiten wurden zu einem großen Teil von Gefangenen des Konzentrationslagers Reichenau durchgeführt.

Innsbruck was attacked a total of twenty-two times between 1943 and 1945. Almost 3833, i.e. almost 50%, of the city's buildings were damaged and 504 people died. Fortunately, the city was only the victim of targeted attacks. German cities such as Hamburg or Dresden were completely razed to the ground by the Allies with firestorms and tens of thousands of deaths within a few hours. Many buildings such as the Jesuit Church, Wilten Abbey, the Servite Church, the cathedral and the indoor swimming pool in Amraserstraße were hit.

Historic buildings and monuments received special treatment during the attacks. The Goldene Dachl was protected with a special construction, as was Maximilian's sarcophagus in the Hofkirche. The figures in the Hofkirche, the Schwarzen Mannderwere brought to Kundl. The Mother of Mercy, the famous picture from Innsbruck Cathedral, was transferred to Ötztal during the war.

The air-raid shelter tunnel south of Innsbruck on Brennerstrasse and the markings of houses with air-raid shelters with their black squares and white circles and arrows can still be seen today. In Pradl, where next to Wilten most of the buildings were damaged, bronze plaques on the affected houses indicate that they were hit by a bomb.

Innsbruck and National Socialism

In the 1920s and 30s, the NSDAP also grew and prospered in Tyrol. The first local branch of the NSDAP in Innsbruck was founded in 1923. With "Der Nationalsozialist - Combat Gazette for Tyrol and Vorarlberg“ erschien ein eigenes Wochenblatt. 1933 erlebte die NSDAP auch in Innsbruck einen kometenhaften Aufstieg. Die allgemeine Unzufriedenheit und Politikverdrossenheit der Bürger und theatralisch inszenierte Fackelzüge durch die Stadt samt hakenkreuzförmiger Bergfeuer auf der Nordkette im Wahlkampf verhalfen der Partei zu einem großen Zugewinn. Über 1800 Innsbrucker waren Mitglied der SA, die ihr Quartier in der Bürgerstraße 10 hatte. Konnten die Nationalsozialisten bei ihrem ersten Antreten bei einer Gemeinderatswahl 1921 nur 2,8% der Stimmen erringen, waren es bei den Wahlen 1933 bereits 41%. Neun Mandatare, darunter der spätere Bürgermeister Egon Denz und der Gauleiter Tirols Franz Hofer, zogen in den Gemeinderat ein. Nicht nur die Wahl Hitlers zum Reichskanzler in Deutschland, auch Kampagnen und Manifestationen in Innsbruck verhalfen der ab 1934 in Österreich verbotenen Partei zu diesem Ergebnis. Wie überall waren es auch in Innsbruck vor allem junge Menschen, die sich für den Nationalsozialismus begeisterten. Das Neue, das Aufräumen mit alten Hierarchien und Strukturen wie der katholischen Kirche, der Umbruch und der noch nie dagewesene Stil zogen sie an. Besonders unter den großdeutsch gesinnten Burschen der Studentenverbindungen und vielfach auch unter Professoren war der Nationalsozialismus beliebt.

When the annexation of Austria to Germany took place in March 1938, a majority of almost 99% in Innsbruck also voted in favour. Even before Federal Chancellor Schuschnigg gave his last speech to the people before handing over power to the National Socialists with the words "God bless Austria" had closed on 11 March 1938, the National Socialists were already gathering in the city centre to celebrate the invasion of the German troops. The swastika flag was hoisted at the Tyrolean Landhaus, then still in Maria-Theresienstraße.

On 12 March, the people of Innsbruck gave the German military a frenetic welcome. A short time later, Adolf Hitler visited Innsbruck in person to be celebrated by the crowd. Archive photos show a euphoric crowd awaiting the Führer, the promise of salvation. After the economic hardship of the interwar period, the economic crisis and the governments under Dollfuß and Schuschnigg, people were tired and wanted change. What kind of change was initially less important than the change itself. "Showing them up there“, das war Hitlers Versprechen. Wehrmacht und Industrie boten jungen Menschen eine Perspektive, auch denen, die mit der Ideologie des Nationalsozialismus an und für sich wenig anfangen konnten. Dass es immer wieder zu Gewaltausbrüchen kam, war für die Zwischenkriegszeit in Österreich ohnehin nicht unüblich. Anders als heute war Demokratie nichts, woran sich jemand in der kurzen, von politischen Extremen geprägten Zeit zwischen der Monarchie 1918 bis zur Ausschaltung des Parlaments unter Dollfuß 1933 hätte gewöhnen können. Was faktisch nicht in den Köpfen der Bevölkerung existiert, muss man nicht abschaffen.

Tyrol and Vorarlberg were combined into a Reichsgau with Innsbruck as its capital. There was no armed resistance, as the left in Tyrol was not strong enough. There were isolated instances of unorganised subversive behaviour by the Catholic population, especially in some rural communities around Innsbruck, and it was only very late that organised resistance was able to gain a foothold in Innsbruck.

However, the regime under Hofer and Gestapo chief Werner Hilliges did a great job of suppression. In Catholic Tyrol, the Church was the biggest obstacle. During National Socialism, the Catholic Church was systematically combated. Catholic schools were converted, youth organisations and associations were banned, monasteries were closed, religious education was abolished and a church tax was introduced. Particularly stubborn priests such as Otto Neururer were sent to concentration camps. Local politicians such as the later Innsbruck mayors Anton Melzer and Franz Greiter also had to flee or were arrested. To summarise the violence and crimes committed against the Jewish population, the clergy, political suspects, civilians and prisoners of war would go beyond the scope of this book.

The Gestapo headquarters were located at Herrengasse 1, where suspects were severely abused and sometimes beaten to death with fists. In 1941, the Reichenau labour camp was set up in Rossau near the Innsbruck building yard. Suspects of all kinds were kept here for forced labour in shabby barracks. Over 130 people died in this camp consisting of 20 barracks due to illness, the poor conditions, labour accidents or executions.

Prisoners were also forced to work at the Messerschmitt factory in the village of Kematen, 10 kilometres from Innsbruck. These included political prisoners, Russian prisoners of war and Jews. The forced labour included, among other things, the construction of the South Tyrolean settlements in the final phase or the tunnels to protect against air raids in the south of Innsbruck. In the Innsbruck clinic, disabled people and those deemed unacceptable by the system, such as homosexuals, were forcibly sterilised.

The memorials to the National Socialist era are few and far between. The Tiroler Landhaus with the Liberation Monument and the building of the Old University are the two most striking memorials. The forecourt of the university and a small column at the southern entrance to the hospital were also designed to commemorate what was probably the darkest chapter in Austria's history.