Sonnenburgplatz

Sonnenburgstraße / Stafflerstraße

Worth knowing

When the Innsbruck municipal council decided in 2016 to "The pasture" to be felled, a storm of indignation broke out. Every trained Innsbruck resident immediately knew which tree it was. The city council for urban planning was inundated with emails in which outraged citizens gave free rein to their emotions over the loss of the tree. All the shouting and screaming did not help. The tree was decrepit and diseased and posed a safety risk due to its imposing size.

The willow in question stood on Sonnenburgplatz, a small inner-city roundabout in Wilten. It covered a stone fountain consisting of two intertwined dolphins spouting water into two shell basins. The square offered neither a cosy bench nor did it commemorate a special event in the city's history. No famous artist had designed it and the once customary title of the fountain Salt and pepper fountain was hardly known to anyone. It was only with the imminent disappearance of the pasture that the people of Innsbruck consciously rediscovered the place, which had long gone unnoticed and overlooked in everyday life.

The fountain was installed on the square in front of the railway station in 1886 to welcome arriving guests to the up-and-coming tourist city of Innsbruck. The two dolphins, symbolising peace and harmony, were the inspiration for the design. When Baron Johann von Sieberer realised his plan in 1905 to celebrate the unification of Innsbruck and Wilten with his much more grandiose Unification fountain the dolphin fountain was moved to Wilten to its current location near the Wilten state railway station, which opened in 1883 and is now the Westbahnhof. The two coats of arms of Innsbruck and Wilten were probably engraved in one of the basins at a later date.

From the 1880s, Sonnenburgplatz developed into Wilten's posh neighbourhood. The name recalls the sovereign jurisdiction of Sonnenburg, which had its origins in the Middle Ages above Mount Isel. Similar to Claudiaplatz in Saggen, residential buildings for the wealthy bourgeoisie were built in the style of the time in Wilten, which was still an independent neighbourhood at the time. A picture postcard from 1910 shows the expanse and splendour of the square, where a cyclist presents her modern sports equipment, without a willow, mind you.

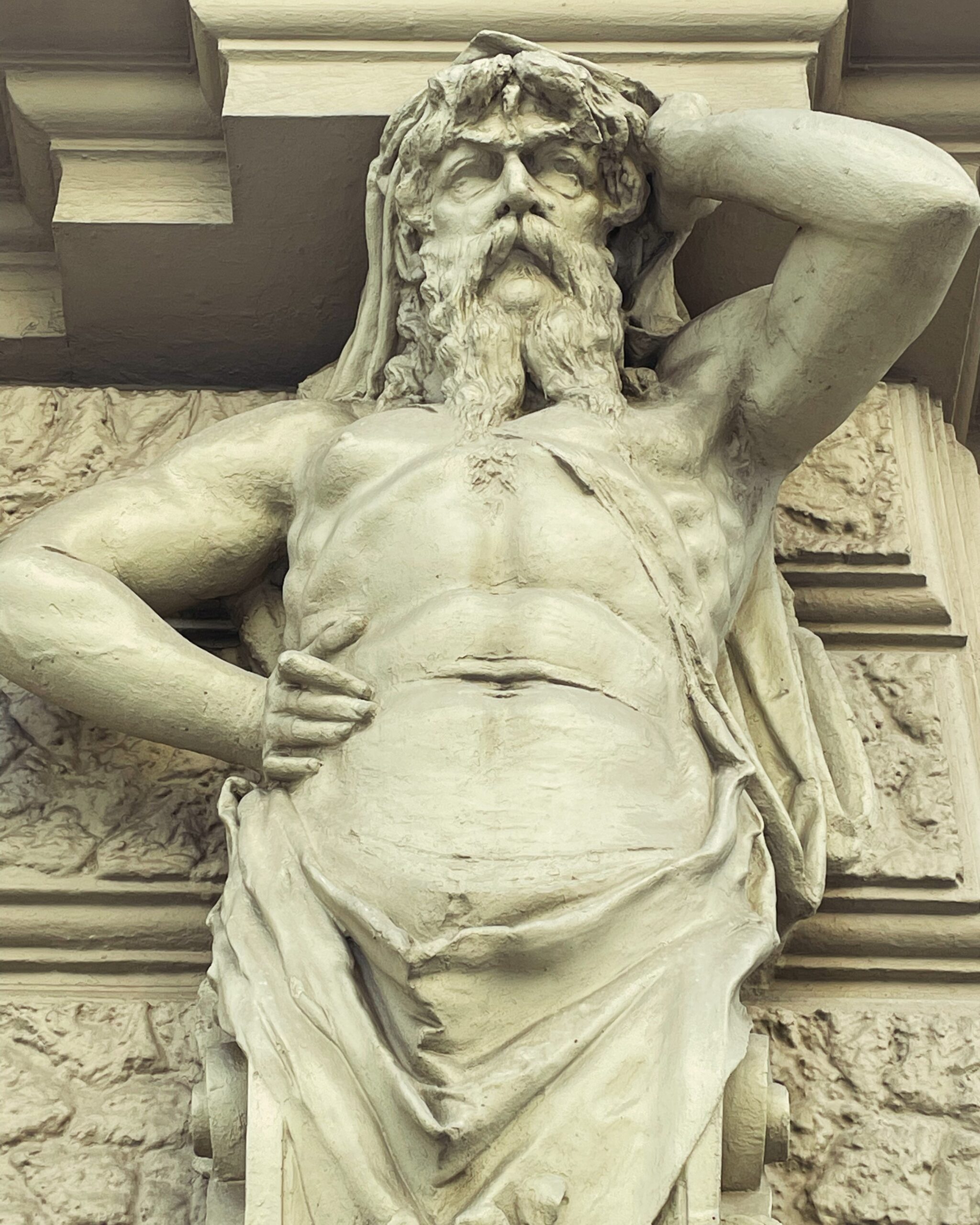

The architectural highlight of the ensemble is the 1902 historicist-style Sonnenburg on the south-west side of the square with its presidential balcony and rich decorations. The Wilhelminian style houses in the side streets are also worth seeing. The statues of bare-breasted ladies and bearded gentlemen at Sonnenburgstraße 17 and the beautiful facades of the colourful buildings in Stafflerstraße to the west of the square allow you to travel back in time. Belle Époque.

By the way: the newly planted tree is growing vigorously and will soon be a worthy, stately successor. What is more exciting is whether it will be possible to upgrade Sonnenburgplatz by freeing it from traffic so that it once again becomes a postcard-worthy motif in Innsbruck's cityscape.

March 1848... and what it brought

The year 1848 occupies a mythical place in European history. Although the hotspots were not to be found in secluded Tyrol, but in the major metropolises such as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Milan and Berlin, even in the Holy Land however, the revolutionary year left its mark. In contrast to the rural surroundings, an enlightened educated middle class had developed in Innsbruck. Enlightened people no longer wanted to be subjects of a monarch or sovereign, but citizens with rights and duties towards the state. Students and freelancers demanded political participation, freedom of the press and civil rights. Workers demanded better wages and working conditions. The omnipotence of the church was called into question.

In March 1848, this socially and politically highly explosive mixture erupted in riots in many European cities. In Innsbruck, students and professors celebrated the newly enacted freedom of the press with a torchlight procession. On the whole, however, the revolution proceeded calmly in the leisurely Tyrol. It would be foolhardy to speak of a spontaneous outburst of emotion; the date of the procession was postponed from 20 to 21 March due to bad weather. There were hardly any anti-Habsburg riots or attacks; a stray stone thrown into a Jesuit window was one of the highlights of the Alpine version of the 1848 revolution. The students even helped the city magistrate to monitor public order in order to show their gratitude to the monarch for the newly granted freedoms and their loyalty.

The initial enthusiasm for bourgeois achievements was quickly replaced by German nationalist, patriotic fervour in Innsbruck. On 6 April 1848, the German flag was waved by the governor of Tyrol during a ceremonial procession. A German flag was also raised on the city tower. Tricolour was hoisted. While students and conservatives disagreed on social issues such as freedom of the press, they shared a dislike of the Italian independence movement. Innsbruck students and marksmen marched to Trentino with the support of the k.k. army leadership to Trentino and

The city, home to many Italian speakers, became the arena for this nationality conflict. Combined with copious amounts of alcohol, anti-Italian sentiment in Innsbruck posed more of a threat to public order than civil liberties. An argument between a German-speaking craftsman and an Italian-speaking Ladin, both actually Tyroleans, escalated to such an extent that it almost led to a pogrom against the numerous businesses and restaurants owned by Italian-speaking Tyroleans.

When things continued to boil in Vienna even after March, Emperor Ferdinand fled to Tyrol in May. Innsbruck was once again the emperor's residence, if only for one summer. According to press reports from this time, he was received enthusiastically by the population.

"Wie heißt das Land, dem solche Ehre zu Theil wird, wer ist das Volk, das ein solches Vertrauen genießt in dieser verhängnißvollen Zeit? Stützt sich die Ruhe und Sicherheit hier bloß auf die Sage aus alter Zeit, oder liegt auch in der Gegenwart ein Grund, auf dem man bauen kann, den der Wind nicht weg bläst, und der Sturm nicht erschüttert? Dieses Alipenland heißt Tirol, gefällts dir wohl? Ja, das tirolische Volk allein bewährt in der Mitte des aufgewühlten Europa die Ehrfurcht und Treue, den Muth und die Kraft für sein angestammtes Regentenhaus, während ringsum Auflehnung, Widerspruch. Trotz und Forderung, häufig sogar Aufruhr und Umsturz toben; Tirol allein hält fest ohne Wanken an Sitte und Gehorsam, auf Religion, Wahrheit und Recht, während anderwärts die Frechheit und Lüge, der Wahnsinn und die Leidenschaften herrschen anstatt folgen wollen. Und während im großen Kaiserreiche sich die Bande überall lockern, oder gar zu lösen drohen; wo die Willkühr, von den Begierden getrieben, Gesetze umstürzt, offenen Aufruhr predigt, täglich mit neuen Forderungen losgeht; eigenmächtig ephemere- wie das Wetter wechselnde Einrichtungen schafft; während Wien, die alte sonst so friedliche Kaiserstadt, sich von der erhitzten Phantasie der Jugend lenken und gängeln läßt, und die Räthe des Reichs auf eine schmähliche Weise behandelt, nach Laune beliebig, und mit jakobinischer Anmaßung, über alle Provinzen verfügend, absetzt und anstellt, ja sogar ohne Ehrfurcht, den Kaiaer mit Sturm-Petitionen verfolgt; während jetzt von allen Seiten her Deputationen mit Ergebenheits-Addressen mit Bittgesuchen und Loyalitätsversicherungen dem Kaiser nach Innsbruck folgen, steht Tirol ganz ruhig, gleich einer stillen Insel, mitten im brausenden Meeressturme, und des kleinen Völkchens treue Brust bildet, wie seine Berge und Felsen, eine feste Mauer in Gesetz und Ordnung, für den Kaiser und das Vaterland."

In 1848, Ferdinand left the throne to the young Franz Josef I. In July 1848, the first parliamentary session was held in the Court Riding School in Vienna. The first constitution was enacted. However, the monarchy's desire for reform quickly waned. The new parliament was an imperial council, it could not pass any binding laws, the emperor never attended it during his lifetime and did not understand why the Danube Monarchy, as a divinely appointed monarchy, needed this council.

Nevertheless, the liberalisation that had been gently set in motion took its course in the cities. Innsbruck was given the status of a town with its own statute. Innsbruck's municipal law provided for a right of citizenship that was linked to ownership or the payment of taxes, but legally guaranteed certain rights to members of the community. Birthright citizenship could be acquired by birth, marriage or extraordinary conferment and at least gave male adults the right to vote at municipal level. If you got into financial difficulties, you had the right to basic support from the town.

On 2 June 1848, the first issue of the liberal and pro-German Innsbrucker Zeitung was published, from which the above article on the arrival of the Emperor in Innsbruck is taken. The previously abolished censorship was partially reintroduced. Newspaper publishers had to undergo some harassment by the authorities. Newspapers were not allowed to write against the provincial government, the monarchy or the church.

"Anyone who, by means of printed matter, incites, instigates or attempts to incite others to take action which would bring about the violent separation of a part from the unified state... of the Austrian Empire... or the general Austrian Imperial Diet or the provincial assemblies of the individual crown lands.... Imperial Diet or the Diet of the individual Crown Lands... violently disrupts... shall be punished with severe imprisonment of two to ten years."

After Innsbruck replaced Meran as the provincial capital in 1849 and thus finally became the political centre of Tyrol, political parties were formed. From 1868, the liberal and Greater German orientated party provided the mayor of the city of Innsbruck. The influence of the church declined in Innsbruck in contrast to the surrounding communities. Individualism, capitalism, nationalism and consumerism stepped into the breach. New worlds of work, department stores, theatres, cafés and dance halls did not supplant religion in the city either, but the emphasis changed as a result of the civil liberties won in 1848.

Perhaps the most important change to the law was the Basic relief patent. In Innsbruck, the clergy, above all Wilten Abbey, held a large proportion of the peasant land. The church and nobility were not subject to taxation. In 1848/49, manorial rule and servitude were abolished in Austria. This meant that land rents, tithes and roboters were abolished. The landlords received one third of the value of their land from the state as part of the land relief, one third was regarded as tax relief and one third of the relief had to be paid by the farmers themselves. The farmers were able to pay off this amount in instalments over a period of twenty years. The after-effects can still be felt today. The descendants of the successful farmers of the time enjoy the fruits of prosperity through their inherited landholdings, which can be traced back to the land relief of 1848, as well as political influence through the sale of land for housing, leases and payments from the public purse for infrastructure projects.

Medieval and early modern town law

Innsbruck, heute selbsternannte Weltstadt, hatte sich von einem römischen Castell über ein Kloster, zu dem mehrere Weiler gehörten zu einer Marktsiedlung und erst nach Hunderten von Jahren zu einer rechtlich anerkannten Stadt entwickelt. Mit dieser rechtlichen Anerkennung gingen Rechte und Pflichten einher. Verbunden mit dem vom Landesfürsten verliehenen Stadtrecht war das Marktrecht, das Zollrecht und eine eigene Gerichtsbarkeit. Bürger mussten im Gegenzug den Bürgereid leisten, der zu Steuern und Wehrdienst verpflichtete und die Stadt mit Mauer und Wehranlage sichern. Ab 1511 war der Stadtrat auch verpflichtet, laut dem Landlibell Kaiser Maximilians ein Kontingent an Wehrpflichtigen im Falle der Landesverteidigung zu stellen. Darüber hinaus gab es Freiwillige, die sich im Freifähnlein der Stadt zum Kriegsdienst melden konnten, so waren zum Beispiel bei der Türkenbelagerung Wiens 1529 auch Innsbrucker unter den Stadtverteidigern. Der Sold war vor allem für die ärmeren Bürger reizvoll. Die Stadtbürger unterlagen damit nicht mehr direkt dem Landesfürsten, sondern der städtischen Gerichtsbarkeit, zumindest innerhalb der Stadtmauern. Das geflügelte Wort "Stadtluft macht frei" rührt daher, dass man nach einem Jahr in der Stadt von allen Verbindlichkeiten seines ehemaligen Herrn frei war. Faktisch war es der Übergang von einem Rechtsystem in ein anderes. Um 1500 änderte sich die Situation im Zuzug. Der Platz war eng geworden im neuen, rasch wachsenden Innsbruck unter Maximilian I. Es war nur noch freien Untertanen aus ehelicher Geburt möglich, das Stadtrecht zu erlangen. Nicht mehr jeder durfte in die Stadt ziehen. Kaufleute und Finanziers verzichteten auf dieses Recht meist, war es doch mit allerhand Pflichten verbunden, die bei den mobilen Schichten dieser Zeit die Anreize weit überstiegen. Um Stadtbürger zu werden, mussten entweder Hausbesitz oder Fähigkeiten in einem Handwerk nachgewiesen werden, an der die Zünfte der Stadt interessiert waren. Diese Handwerkszünfte übten teilweise eine eigene Gerichtsbarkeit neben der städtischen Gerichtsbarkeit unter ihren Mitgliedern aus. Löhne, Preise und das soziale Leben wurden von den Zünften unter Aufsicht des Landesfürsten geregelt. Man könnte von einer frühen Sozialpartnerschaft sprechen, sorgten die Zünfte doch auch für die soziale Sicherheit ihrer Mitglieder bei Krankheit oder Berufsunfähigkeit. Die einzelnen Gewerbe wie Schlosser, Gerber, Plattner, Tischler, Bäcker, Metzger oder Schmiede hatten jeweils ihre Zunft, der ein Meister vorstand. Es waren soziale Strukturen innerhalb der Stadtstruktur, die großen Einfluss auf die Politik hatten, konnten sie das Wahlverhalten ihrer Mitglieder stark mitbestimmen. Handwerker zählten, anders als Bauen, zu den mobilen Schichten im Mittelalter und der frühen Neuzeit. Sie gingen nach der Lehrzeit auf die Walz, bevor sie sich der Meisterprüfung unterzogen und entweder nach Hause zurückkehrten oder sich in einer anderen Stadt niederließen. Über Handwerker erfolgte nicht nur Wissenstransfer, auch kulturelle, soziale und politische Ideen verbreiteten sich in Europa durch sie. Ab dem 14. Jahrhundert besaß Innsbruck nachweisbar einen Stadtrat und einen Bürgermeister, der von der Bürgerschaft jährlich gewählt wurde. Es waren anderes als heute keine geheimen, sondern öffentliche Wahlen, die alljährlich rund um die Weihnachtszeit abgehalten wurden. Da nicht jeder Einwohner Bürger war, kann man auch nicht von einer Demokratie sprechen, eher war es eine Wahl der Oberschicht, die ihre Vertreter wählte. Im Innsbrucker Geschichtsalmanach von 1948 findet man Aufzeichnungen über die Wahl des Jahres 1598.

The Feast of St. Erhard, i.e., January 8th, played a significant role in the lives of the citizens of Innsbruck each year. On this day, they gathered to elect the city officials, namely the mayor, city judge, public orator, and the twelve-member council. A detailed account of the election process between 1598 and 1607 is provided by a protocol preserved in the city archive: "... The ringing of the great bell summoned the council and the citizenry to the town hall, and once the honorable council and the entire community were assembled at the town hall, the honorable council first convened in the council chamber and heard the farewell of the outgoing mayor of the previous year, Augustin Tauscher."

Der Bürgermeister vertrat die Stadt gegenüber den anderen Ständen und dem Landesfürsten, der die Oberherrschaft über die Stadt je nach Epoche mal mehr, mal weniger intensiv ausübte. Jeder Stadtrat hatte eigene, klar zugeteilte Aufgaben zu erfüllen wie die Überwachung des Marktrechts, die Betreuung des Spitals und der Armenfürsorge oder die für Innsbruck besonders wichtige Zollordnung. Bei all diesen politischen Vorgängen sollte man sich stets in Erinnerung rufen, dass Innsbruck im 16. Jahrhundert etwa 5000 Einwohner hatte, von denen nur ein kleiner Teil das Bürgerrecht besaß. Besitzlose, fahrendes Volk, Erwerbslose, Dienstboten, Diplomaten, Angestellte, ab dem 17. Jahrhundert Studenten, leider auch Frauen waren keine wahlberechtigten Bürger. Die Wahlen basierten also auf persönlichen Verbindlichkeiten und Bekanntschaften in dieser kleinen Gemeinde. Ebenfalls ab dem 14. Jahrhundert mussten die Steuern, die von den Bürgern gezahlt wurden, nicht mehr an den Landesfürsten weitergegeben werden. Es gab eine fixe Abgabe von der Stadt an den Landesfürsten. Welche Gruppe innerhalb der Stadt welche Steuer zu bezahlen hatte, konnte die Stadtregierung selbst festlegen. Die Differenz zwischen den Einnahmen und den Ausgaben durfte die Stadt nach ihrem Gutdünken verwalten. Zu den Ausgaben neben der Verteidigung gehörte die Armenfürsorge. Notleidende Bürger konnten in der „Siedelküche" meals, if they had the civil rights. Building rights were also the responsibility of the city administration. As in most medieval towns, the wooden buildings within the town walls fell victim to flames more often than the inhabitants would have liked. Another point that was regulated in the town charter was the right to organise markets. The town had control over the goods on offer and their quantity and quality. Bread, for example, was sold by the "Bred guardian" were weighed in the bread bank in the town hall to prevent usury, which was a punishable offence. Interestingly, the town council could also appoint the pastor. Pastoral care was a real need, so the quality of the sermon or choir singing was very important. Compliance with religious order was also monitored by the city. Heretics and theologically rebellious people were not reprimanded by the church, but by the city government and, in some cases, even sent to prison.

In addition to the taxes that citizens had to pay, customs duties were an important source of income for Innsbruck. Customs duties were levied at the city gate at the Inn bridge. There were two types of customs duty. The small duty was based on the number of draught animals in the wagon, the large duty on the type and quantity of goods. The customs revenue was shared between Innsbruck and Hall. Hall had the task of maintaining the Inn bridge. With the increasing centralisation under Maria Theresa and Joseph II, taxes and customs duties were gradually centralised and collected by the Imperial Court Chamber. As a result, Innsbruck, like many municipalities at the time, lost a large amount of revenue, which was only partially compensated for by equalisation.

Contrary to popular belief, the Middle Ages were not a lawless time of arbitrariness. In Innsbruck, as well as in the province of Tyrol, there was a code that regulated right and wrong as well as the rights and duties of citizens very precisely. These regulations changed according to the customs of the time. The penal system also included less humane methods than are common today, but torture was not used indiscriminately and arbitrarily. However, torture was also regulated as part of the procedure in particularly serious cases. Until the 17th century, suspects and criminals in Innsbruck were held and tortured in the herb tower at the south-east corner of the city wall, on today's Herzog-Otto-Ufer. The medieval court days were held at the "Dingstätte" is held outdoors. The tradition of the Thing goes back to the old Germanic Thingwhere all free men gathered to dispense justice. The city council appointed a judge who was responsible for all offences that were not subject to the blood court. Punishments ranged from fines to pillorying and imprisonment. There was no police force, but the town magistrate employed servants and town watchmen were posted at the town gates to keep the peace. It was a civic duty to help catch criminals. Vigilante justice was forbidden. Serious crimes such as theft, murder and arson were subject to the blood law. The provincial court still had jurisdiction over these offences. In the case of Innsbruck, the provincial court was on the Sonnenburgwhich was located south above Innsbruck. From 1817 - 1887 the Leuthaus the seat of the court judge at Wilten Abbey (67). Over the years, the places of execution were located in several places, usually outside the town walls. For a long time, a gallows was set up on a hill in today's Dreiheiligen district next to the main road that ran past here. The corpses were often left hanging for a long time as a deterrent. The Köpflplatz befand sich an der heutigen Weiherburggasse in AnpruggenIt was not uncommon for the condemned man to give his executioner a kind of tip so that he would endeavour to aim as accurately as possible in order to make the execution as painless as possible. Sensational delinquents such as the "heretic" Jakob Hutter (87) or the captured leaders of the peasant uprisings of 1525 and 1526 were executed before the Goldenen Dachl executed in a manner suitable for the public. "Embarrassing" punishments such as quartering or wheeling, from the Latin word poena were not the order of the day, but could be ordered in special cases. From the late 15th century, Innsbruck's executioner was centralised and responsible for several courts and was based in Hall. Executions were a public demonstration of the authorities' power. It was seen as a way of cleansing society of criminals. The executed were buried outside the consecrated area of the cemeteries.

With the centralisation of law under Maria Theresa and Joseph II in the 18th century and the General Civil Code in the 19th century under Franz I, the law passed from cities and sovereigns to the monarch and their administrative bodies at various levels. Under Joseph II, the death penalty was even suspended for a short time. Torture had already been abolished before then. The Enlightenment had fundamentally changed the concept of justice, punishment and rehabilitation. While it had previously been a criminal offence and sometimes punished with the pillory or worse if a woman gave birth to an illegitimate child, this was no longer a criminal offence. The children were handed over to Catholic foster parents or an orphanage. The Christian morals of the people did not follow suit with the law. Women remained marginalised until well into the 20th century, even though a significant proportion of children were illegitimate. Goethe's Faust recounts the fate of one such woman who killed herself out of shame. The collection of taxes was also centralised, which resulted in a great loss of importance for the local nobility and an increase in the status of civil servants. The new legal concepts also gradually changed the urban landscape. The herb tower as a dungeon became obsolete; instead, a penitentiary was needed, today's Turnus clubhousein St Nicholas.

The development of the legal system to the one we have today in the Republic of Austria and its cities was a long process. While the mayor and the city council are still elected, the judge is appointed at the district court. The employees of the city magistrate are hardly civil servants any more and the young citizens' party, to which the city invites its youngest members on their coming of age, is not very festive or even significant. There are also no more guilds. However, the dispute over who is a "real" Innsbrucker and who is not is a continuity that has persisted to this day. Unfortunately, it is often forgotten that migration and exchange with others have always guaranteed prosperity and made Innsbruck the liveable city it is today.